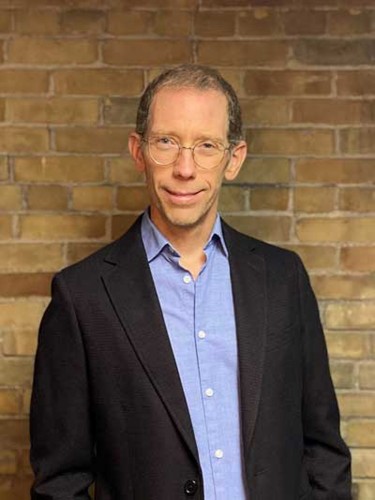

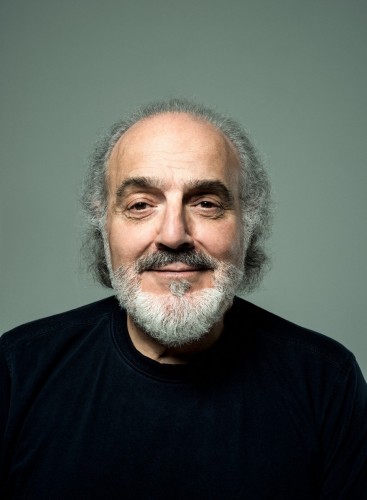

Knowing how busy his schedule was going to be over the course of the spring, I booked my final interview with Peter Oundjian good and early (Thursday, March 8, to be precise). He was in town for New Creations, one of the signature series he created in the course of his 14 years as the TSO’s conductor and music director. I’d had a chance to get a sneak-peek look over the first “post-Oundjian” 2018/19 season before going in to meet him and what struck me immediately was the fact that all the Oundjian signatures are conspicuous by their absence – New Creations, the Decades Project, and most noticeably, Mozart @, which he had launched as Mozart@249 the very first year he arrived – stealing a march on the looming Mozart at 250 hullabaloo, in that endearing blend of cheeky and canny that has characterized his stay here.

Knowing how busy his schedule was going to be over the course of the spring, I booked my final interview with Peter Oundjian good and early (Thursday, March 8, to be precise). He was in town for New Creations, one of the signature series he created in the course of his 14 years as the TSO’s conductor and music director. I’d had a chance to get a sneak-peek look over the first “post-Oundjian” 2018/19 season before going in to meet him and what struck me immediately was the fact that all the Oundjian signatures are conspicuous by their absence – New Creations, the Decades Project, and most noticeably, Mozart @, which he had launched as Mozart@249 the very first year he arrived – stealing a march on the looming Mozart at 250 hullabaloo, in that endearing blend of cheeky and canny that has characterized his stay here.

(As it turned out, he had not looked at the upcoming season at all and in fact had no hand in putting it together. So rather than, as in some previous years, the spring interview being with musical director Peter Oundjian with an enthusiastic agenda of “upcomings” to promote, this was a rather more leisurely and relaxed ramble through this and that, looking back as much as forward. Enjoy.)

WN: So 14 years with the Tokyo String Quartet and then 14 years of this? What’s with that?

Peter Oundjian (laughs): Yes, well it did rather play into my decision – because I knew the time was coming when everyone would need to reinvent themselves a little bit on both sides; so then I looked at that number, 14 years, and said, well, it seems about right. But, truth be told, we were hopeful we had found a successor so I thought, “Well, this is going to be smooth, because you always want to know that your organization is going to be in good hands when you leave.” Whenever I wake up at night it’s “What do they need, what could go wrong, what do they need going forward, what do I do about this particular personnel issue, conflict, this sound issue, what about fundraising, why are we not having more success in this area?” There are just a million things to think about… More than there were with the [Tokyo] Quartet, actually. I mean with the quartet it was like going to the moon. “Here’s your schedule for the next two years… Go!” 140 cities every year. Here are the programs. Practise. Rehearse!

If this is Houston it must be Opus 131 again… that kind of thing?

Exactly. Here it’s been different every week. I mean figuring out the guest conductors. Who the orchestra really enjoys? Who challenges the orchestra the most? Who simply makes the orchestra feel good. What’s the right balance? It’s an enormous task, and really challenging because it’s so multifaceted. There’s a tremendous emotional input that goes into it – and intellectual. So when you decide the time has come to move into a different place in your own life and the life of the organization, the one thing you worry about is – and this is maybe going to sound a bit self-centred – will people realize how much attention goes into this? And… You don’t want a vacuum, put it that way. That’s what you worry about, because when I arrived there was a serious vacuum. The first few times I conducted this orchestra there had been serious leadership vacuums on both sides. I mean certainly we had not had luck with CEOs staying very long, and the right kind of vision. Jukka-Pekka [Saraste] had left several years before.

Yes, there was an uneasiness at the time. I agree. But is there going to be less of a vacuum this time round?

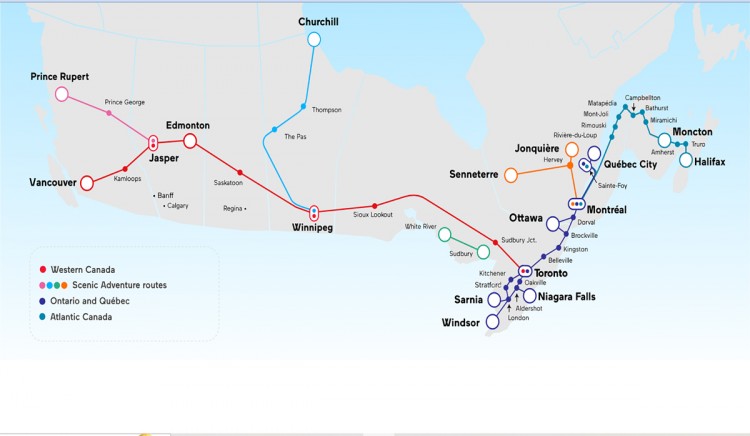

Oh I think so. Very much. First of all, Sir Andrew Davis is a great friend and is somebody everybody trusts implicitly, and he has a very strong relationship with the city and with the orchestra. But also I have to say we are in a less tenuous situation. The morale of the orchestra is in a very different place from where it was in the 90s, and that’s by the way not to point fingers at Jukka-Pekka in any way. He came into a very difficult economic situation, where the Canadian government was backing away not just from support of the TSO but from the arts in general – and that’s what brought about the tax structure change, by the way, more of a feeling that the private sector should enable it, if we believe in it, then let the private sector, with the help of the government via new tax structures, show their vision and prove their worth.

So in those terms, Sir Andrew is coming in as the vacuum cleaner…

Well put! (laughs) Right. I mean, if the orchestra had come to a decision regarding a conductor in the last two years since I announced my departure it would have been different, but they didn’t… it was close but it didn’t happen.

It was close?

It was. But the person took another position.

From an audience perspective these searches are pretty boring actually – certainly not a public blood sport. I mean, nobody wants to be known as the shortlisted candidate who didn’t get the job.

Exactly. It’s the opposite of politics, and so it should be. Nobody should know who’s on the shortlist, and at this point, by the way I don’t think there’s even a shortlist. There’s a lot of discovery going on.

Listening to you talking about capital gains and tax structures and the like, is that one of the hats you’ll be hoping to wear less moving on?

It’s a good question. I mean, I have been music director of two organizations for almost seven years now – I took on the Royal Scottish National Orchestra (RSNO) officially in 2012 but before that you’re [still] doing all the planning. I have been working in that kind of “administrative capacity” for two symphony orchestras for the past seven years or so. So definitely it was on my mind that now’s the time to focus more exclusively on musical discoveries, and musical adventures and musical thinking. Also I will be doing a tiny bit more work at Yale. Well, I shouldn’t say tiny, more work at Yale anyway. I have taken over the Yale Philharmonia – the Yale Music School is one of the postgraduate schools at Yale and it’s the only major research university in North America that has a dedicated performance music school and it’s tuition-free so the standard is very high. I’ve been a professor there since 1981 actually…

Tokyo String Quartet had a Yale residency, right?

Exactly. Part of my obligation as a member of the quartet was teaching chamber music at Yale.

So I have had a very close affiliation with Yale. It’s very close to my home in Connecticut and it’s meant a lot to me over the years. So I was asked if I would take over the program, which is an interesting ensemble in that they prepare in the same way as a professional orchestra – all the rehearsals are within one week – six rehearsals. So not only is it easier for me to be involved, but…

… Also a taste of the real world for the orchestra.

Exactly! And not only that, it means I can bring in international guest conductors who can give a week, but could never have given two or three weeks in the old way of preparing.

So tell me a bit more about the RSNO music directorship. I assume it has its own mix of rewards and challenges, but have there been transferable solutions from here to there?

The important thing is not to take anything for granted, because if you go with your expectations rather than with your observations you are in trouble. Similar and different problems and exciting rewards. It’s been a wonderful experience with RSNO: it’s an orchestra that plays with a great deal of expressivity. We’ve been able to tour them to China and Europe and the United States. And a lot of recordings. That’s been one of the best things with the RSNO because at the TSO, as you know, we don’t have a contract that really allows us to make recordings. The only recordings we have made here are live, with possibly a patch session. Two performances and you have to hope there isn’t a bar where things didn’t go well on both nights. But in the RSNO you actually really record. You go in and you do the thing and if something goes wrong you work it out. And that allows people to play with a lot of risk. When you are recording live you want it to be exciting but the risk element is a really tricky one. I have to say, though, the TSO has been amazing, really amazing in their live recordings. If you listen to them… I mean we did The Planets and Rite of Spring in one night! And I listen to those recordings sometimes and say “If we had done those in recording sessions, what would have been more, quote, perfect.” Some of the most exciting recordings are live; they are not the most perfect but…

But at least you can hear the hall breathe…

Right. So with the RSNO it’s a different kind of contract, where a service can mean a rehearsal or it can be a concert or a recording session. In the States and North America generally, that’s not the case. Recordings have to be in a separate contract.

Has raising kids in this city helped shape your perspective on what needed to be done at the TSO to build bridges to that next-generation audience that everyone talks about as some kind of holy grail?

Has raising kids in this city helped shape your perspective on what needed to be done at the TSO to build bridges to that next-generation audience that everyone talks about as some kind of holy grail?

I’d say first that one’s own children are not a good gauge because they’ve grown up with music around them all the time and they play instruments and so on. But for me, reaching out is not just a generational thing. I have always tried to make the concert hall a friendly place, a non-elitist place. And sometimes that’s been quite trying, because when you are about to go out and really perform… I mean, when an actor’s about to go out and be Hamlet they really don’t want to go out before and spend five minutes explaining the play. How do you gain the credibility of then being Hamlet? Obviously it’s not quite the same when I step onto the podium. I am not becoming another person, but when I start to conduct I am becoming an interpreter, and hopefully some kind of transmitter of feeling and atmosphere and everything else.

So it’s a tough transition from “mine genial host”?

Exactly. You’re in two very different modes. And certainly, there are certain pieces before which I have not spoken. Or have tried to separate the speaking from the performance in some way. But people have been generally appreciative of my welcoming them, trying to give them some sense of what they are listening to and what to listen for.

To demystify the thing…

Right. So to get to your question, if I can help people who might otherwise not come back, and who might now say “I have friends who would actually enjoy this,” and even bring someone with them the next time, then that’s gratifying. And all in all, the size of our audiences is gratifying.

I remember a performance of the Tchaikovsky Sixth where you spoke from the front of the stage. The second mezzanine was filled with first-timers. You were explaining the structure of the piece how the Third and Fourth Movements are a reversal from the norm.

In terms of character you mean?

Yes, exactly. And you said “So don’t be surprised if you want to applaud at the end of the third movement.”

Ah yes, I remember.

And then you actually went further – you said “In fact, if you feel like applauding, go right ahead because this ‘rule’ we have about not applauding between movements of a symphony actually didn’t come into effect until a decade after this symphony was written and performed.”

That’s correct. Yes.

And what was so interesting about that for me was seeing what you earned from that as conductor later on.

How so?

Well, you got to hold the silence at the end of the final movement way, way longer – maybe eight, ten seconds of…

Well, you got to hold the silence at the end of the final movement way, way longer – maybe eight, ten seconds of…

Of meaningful atmosphere. Right.

So I’m really interested to know where you stand on the whole etiquette thing, because what that particular intervention at the beginning did was to disentitle the purists in the audience from being your glare police. And from where I sit, the rewards of that kind of recalibration of what’s okay far outweigh the disadvantages.

Right. So, I’m not convinced that the house rules, developed by Mahler and Schoenberg really, have the same relevance now as they did then. And by that I mean that people behaved pretty badly in concerts then. People talked a lot in the 19th century. It was much less formal, from the reports we hear. And in opera, too. I mean, at La Scala there was cooking and eating going on in the boxes. So they were frustrated that people were not really listening during the movements, and they wanted to take control, to say “No! You’re going to be quiet, and even between the movements you’re going to be silent and not talk because otherwise we can’t get your attention back.” I may be exaggerating slightly, but I think that it was really a reaction to failed listening. Otherwise, how did movements get encored in Beethoven’s time? Because people applauded like crazy. They thought it was so amazing. “Play it again. Play it again. We want to hear that movement again!” Obviously there was a huge reaction to each movement.

That’s a delightful thought.

Now obviously there are certain pieces, certain movements that, when they end – first movement of the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto for example – it’s just plain awkward when it’s silent after that, it so calls for a response. Nobody has any problem with that at the opera. People applaud after the big arias; nobody looks at them and says “What are you doing?” That hasn’t changed. I don’t think applause necessarily interrupts the flow of a symphonic performance. But it depends on the symphony and it depends on the movement. Now I happen to like applause at the end of the third movement in Tchaik Six because I then get to completely destroy their good mood, by hearing when that applause is going to die and then bringing in that devastating chord. I think it’s incredibly dramatic. Much more dramatic than bringing it in out of silence. Personally. But then I come from a family of different kinds of performers too so… I mean you know who my cousin is?

You mean Eric [Idle]?

Exactly. Of all the Monty Python guys he’s the one they all trust with putting on the shows because he understands how people react and what order to do things in. Anyway, all this to say, understanding the theatre of things is very important.

Now, do I want applause after the Adagietto? Of course not. It’s not the end of anything. The silence is very, very powerful. So I think I know when applause is okay and when it’s not, and I hope what I have developed is a kind of trust from people.

And one last thing to say: people with a real love for the symphony, when other people react and clap after a first movement, they should be saying “Wonderful – there are new people in the audience tonight!”

Going way back, the first time I interviewed you, you were standing in the hallway of your house in Connecticut waiting for the movers – Tippett Richardson I’m guessing – to arrive....

(Laughs). You’re right, it was Tippett Richardson. In fact, it was John Novak’s son Dave, who was one of the movers. John has been a fantastic supporter of the TSO.

So on the subject of houses – this is a bit roundabout, but bear with me – when people are selling a house they have lived in, realtors will advise that, yes, it needs to be furnished, but it really shouldn’t be too personal.

Staged.

Yes, exactly. And looking at the upcoming 2018/19 season, that’s what it feels like. Functionally furnished for whoever the new occupants are going to be.

Right, and that’s possibly exactly what it is. As I say I haven’t seen the brochure (not for any intentional reason, I just haven’t got round to it), but that may well be the thinking behind it, because the new person wants to come with a vision.

The Oundjian branding is gone. New Creations is gone. The Decades Project is gone. The Mozart@ series is gone.

Yes, Well the Decades Project, I never really got to complete. I actually loved that project. I have to say I wish it had intrigued people more. It intrigued the people who came, for sure, but I thought it was just so fascinating. It was a good example of the things I like to do. Bartok/Strauss is another example. You know, programming unlikely contemporaries. Or Rachmaninoff and the Impressionists. Or Stravinsky/Brahms. Stravinsky/Brahms was especially indulgent on my part, because Stravinsky was 16 when Brahms died, and I was 16 when Stravinsky died, so I thought “Wow, was Brahms to Stravinsky in his head that great contemporary, living composer?” And yes, he was! As Stravinsky was to me when I was a young man hearing Stravinsky premieres. So I was fascinated by that. It’s all about ways of framing programs. Of storytelling.

So to get back to my point, this coming season doesn’t have that curated, storytelling feel to it. I’m assuming that in a transitional year, with 20 different conductors coming in – I listed them all if you’d like to look – some of whom one might infer are under consideration for the new appointment, one way to truly evaluate the chemistry between candidates and the orchestra is to say “Let’s see what the new people do with the old stuff.”

Very much so. Part of the thinking is you need to see these conductors under the same observational umbrella. It’s sensible. And it’s exciting in a different way. Clearly a lot of the conductors on this list have never been here before. Some of course are old friends. So it’s clear what the concept is. There are some people coming simply because we like to hear them make music with the orchestra – Gunther [Herbig], Pinky [Pinchas Zuckerman], Sir Andrew of course. Others may be under the microscope in some sense. But it’s not a shortlist or anything like that.

And you are completely gone from the picture for the entire season, I see, although I gather you’ll be part of the picture for the 2019/20 again.

That’s right, yes.

So is that part of the “getting the previous occupant out of the way” blank-slate thing we were talking about?

Yes. I think a lot of conductors don’t really step aside properly, it seems to me. I mean, you can look at all kinds of examples. You know, huge farewell and then a couple of weeks later they’re back on the podium again and you’re wondering, well, what was that farewell about then? So it made sense to me to have the announcement of the new season, which I had no hand in, while I’m still in farewell mode, or whatever you want to call it; and to include me in the announcement as music director would not have seemed right. And as for the season, obviously they’re going to be looking at a lot of people over time, and also inviting back well-loved, trusted friends of the orchestra who’ve been here quite a bit and whom they really know. And the following season, all going well, I’ll be back as one of those!

David Perlman can be reached at publisher@thewholenote.com.

/page 8-area-235x283.jpg)