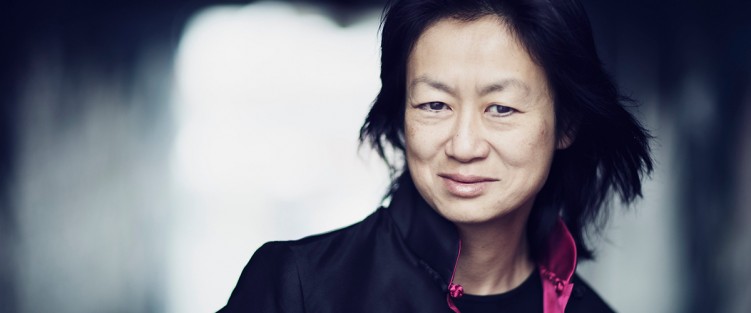

One of Canada’s busiest conductors is just back from Hong Kong, where she conducted Don Quixote from a COVID-proof orchestra pit. She spoke with Lydia Perović via Zoom from her home in Guelph.

One of Canada’s busiest conductors is just back from Hong Kong, where she conducted Don Quixote from a COVID-proof orchestra pit. She spoke with Lydia Perović via Zoom from her home in Guelph.

LP: Hi Judith Yan! Oh, what’s that artwork behind you?

JY: This here is a print of Jackson Pollock. But then this round one here, this is our favourite. It’s by a Guelph-area artist, Chelsea Brant; we have two of her works. She’s fabulous. And this one over here, that’s by Amanda. [Yan’s partner Amanda Paterson, the artistic director of Oakville Ballet and Oakville School of Classical Ballet] And then there’s the dog, have you met the dog? Mexxie, come here buddy, come say hi! He’s the best.

(Mexx the black and white Shih Tzu comes into the frame, checks out what’s going on.)

What were the last eight months like for you? I expect you had a busy start to the year, and then mid-March happened!

I was getting ready to go to Australia in March. The pandemic came and all of a sudden I had six productions cancelled and two symphony concerts gone: a new production of Sleeping Beauty with West Australian Ballet and Dracula later; the Canadian premiere of Powder Her Face by Thomas Adès at Opera on the Avalon, and a premiere of John Estacio’s Ours at the NAC. A second Sleeping Beauty in Hong Kong, and a very cool production of Gluck’s Orfeo at the Kentucky Opera. My farewell concert with the Guelph Symphony Orchestra, where I’ve spent eight years – I absolutely adore them – also had to go, as did my debut with Saskatoon Symphony. Saskatoon are so forward-thinking and carrying on with programming, but we have decided to postpone due to quarantining rules and the changing regulations about indoor gatherings.

So Saskatoonians have been performing before an audience? Ontario is completely closed. I think people will forget why they ever wanted to come to concerts…

So Saskatoonians have been performing before an audience? Ontario is completely closed. I think people will forget why they ever wanted to come to concerts…

This experience in Hong Kong completely changed my mind about that. At first I was concerned that audiences may not come back, but in Hong Kong the 500 allowed seats sold out immediately and when the numbers went even lower, they said, OK we’ll open up another 250. And it sold out. Virtual will never take the place of live performance. Hong Kong had of course gone through SARS and already, since February, had strong protocols in place. Art organizations managed to strike a balance: they were concerned about the welfare of people, and also aware of the impact on businesses, and arts are a big part of it. They continue to support the arts and that philosophy feeds into organizations and empowers them. The Hong Kong Ballet I think never stopped moving. (I think that’s their logo this year too: Don’t Stop Moving.) The minute the city said that you can have six people in a space, they rehearsed with six people. At a time! They persevered, they were patient, they kept working, and as soon as the city said they could open, they were ready. That takes courage, and a positive attitude.

Was this [Don Quixote] an old contract signed ages ago?

No, I was supposed to be conducting Sleeping Beauty and then of course it didn’t happen. But as soon as things started to look positive again, we talked about doing Don Quixote and the contract came.

I said to my manager and my partner, wow I can’t believe this is happening. I signed it, we sent it back and every day I thought, this is probably going to be cancelled. But then the flight booking came, and the list of requirements for quarantine. You have to do a COVID test the minute you land, and then on the tenth day of the 14-day quarantine, and if you test negative, you’re allowed to leave the quarantine. And that’s how it happened. The entire orchestra and the dancers, we all tested one more time before beginning the work.

What was your life between that March and the Hong Kong trip? I believe you accompanied your partner’s ballet classes from the piano for a while?

What was your life between that March and the Hong Kong trip? I believe you accompanied your partner’s ballet classes from the piano for a while?

Oh that! [laughs]. She’s a principal of a wonderful ballet school in its sixth decade, and when the first lockdown happened, we cleared out our dining room and that became the studio. And I said, I haven’t played class in 20 years, but I’d be happy to, and she said, “Sure, that’d be great.” Anyway, I got fired. Supposedly I wasn’t paying enough attention! So I got demoted to tech help. When Zoom goes out on her students’ computers, people call my phone number for tech help. Which is hilarious! I think she probably got back at me for playing silly things on the piano. She’s using recorded music now and has her own perfect playlist.

What I’ve been actually doing is I’ve been preparing and online-meeting with opera companies and orchestras (Kentucky Opera, Opera on the Avalon, Saskatoon Symphony, Hong Kong Ballet) to discuss ways to continue the productions in current circumstances. I’ve been on a granting review committee for Canada Council, on a panel of judges for National Opera Association (opera productions) and in talks with Hong Kong to come up with a viable solution for the orchestra pit. We were the first company to be in the pit since the pandemic.

This period will be interesting because it will make many of us – whatever profession we’re in – decide whether this is really what we want to do. How patient are we and how willing to make the sacrifices. And how positive. For example, Opera on the Avalon have done two commissions in the last three years, and they just announced another commission, to premiere in 2022. I love working with OOTA. It’s nice to be able to work in Canada because the majority of my work is not here.

More opportunities around the globe, I suppose?

Yes. Asia, Australia, US… and nobody ever bats an eyelid that I’m not a man. It’s never been a problem. They just hire you because you’re useful. It’s not a big deal. In Canada, my first appointment was by Richard Bradshaw at the Canadian Opera Company, in 1998 I think. Maestro Bradshaw said once in an interview “I didn’t hire her because she’s a woman, I hired her because …” and then he said some nice things about my work. In 2003, I was hired by Sir Donald Runnicles at San Francisco Opera. So, two men, right? Runnicles didn’t care either that I was a woman, he just hired me. I worked there, Seattle Opera, Polish National Ballet in Warsaw…

It’s not always that easy for women conductors, right? I think it’s oftentimes not even conscious discrimination – it’s like hires like, it’s inertia, so of course men will hire more easily other men, but as you say, there are always those beautiful exceptions.

That’s well put: beautiful exceptions. It’s been like that for the last 20 years. First with Maestro Pierre Hétu, then Maestro Bradshaw and Maestro Runnicles. And I mean, with Ballet, they primarily care that you give them the right tempo and the right phrasing.

Sure, some people will use that excuse, we’d hire more women if they were more competent, and I kind of laugh because they hire incompetent men all the time. You have to hire people when they are incompetent because otherwise how else will they become competent?

That’s exactly the step that’s harder to cross for women and minorities. Young unprepared men are hired all the time because somebody has understood their potential.

Often we look at incompetence as “growing pains,” but for women, people are less forgiving. To women conductors I say: if it doesn’t work in one place, and you really want to do it, get on an airplane and fly somewhere else. There’s always going to be someone who’s going to open the door for you, you just have to work hard enough. The events like this pandemic will certainly test you; you’ll see how many risks you’re willing to take, how far you’re willing to go.

You hear a lot about conductor stamina. How physical is the job? I expect you have to be pretty fit.

You get there step by step and as needed. In my 30s I transitioned from pianist to conductor, but I was a rehearsal conductor and worked for hours on end. I must have injured every part of my back, to a point now where there is no feeling left. So it was gradual, and yes you start with the smaller pieces. For example, Sleeping Beauty is three and a half hours long and it gets harder and harder. When I was in Hong Kong, I would do five of them on a weekend. One on Friday, two on Saturday, two on Sunday. That’s seven hours of conducting a day, with intermissions. Don Quixote is not that long, but strenuous – mentally. About two and a half hours – I did a single and a double-double. You don’t stop moving and you don’t stop thinking. But you have to build up to it.

In Australia, the run is 15 shows. I premiered Dracula there – which is the most amazing music by Wojciech Kilar. It’s difficult and long, and you do 15 of them over two weeks. In Seoul, in Korea, beautiful company, orchestra to die for – we had four readings, one tech with orchestra, three dress rehearsals and five performances; 13 work sessions with the orchestra in the span of week and a half. It’s go-go-go.

Classical music in East Asia is seeing some extraordinary growth?

Yes! In Seoul, the performances are always full. When we come out through the stage door, it’s filled with people who’ve come to thank us. There are pictures, there are flowers, there’s always big support. And in the house, there are seats specifically for children, because there’s demand – they’re like boosters, a child seat on top of the regular seat. The same level of enthusiasm as in Hong Kong.

Renée Fleming was saying in an interview after her East Asia tour that the lineups after the show are incredible. And it’s mostly young people.

Part of it too is that in Asian cultures, schooling is important, education is important, the arts are revered. Highly respected. Your academic success is incomplete without ballet, piano or violin. Most of the kids do everything. I was born in Hong Kong and that is how it worked: I had ballet and piano; it’s part of growing up. I started ballet at four, piano at six. This kind of information starts coming at you at the age of four and six and it doesn’t stop until you finish your high school. You can’t help it, you know?

And being at a live orchestra performance… it’s like opening up an iPod and seeing how everything is made. Oh it’s the horns, that’s what makes that sound! Seventy people in the pit, a hundred people on the stage, without anything being amplified, and it’s all happening before you. How exciting is that.

And before I let you go: what’s next on the horizon?

The symphony concert in Saskatoon has been postponed to the spring, and then the Adès with OOTA that’s scheduled to go in 2021. In 2022, things are starting to come back. Orfeo in Kentucky is rebooked, and we’re waiting to see what’s going to happen with Hong Kong ballet…

It really comes down to the leadership of individual companies. The companies that are very positive are already talking about it and I don’t think they’re being foolhardy, I think they’re being ready. That’s the way one has to look at it. Before each of the performances of Don Q in Hong Kong, Septime Webre the artistic director, who’s also a fabulous choreographer, went on stage and welcomed the audience. He was so gracious and positive and we really needed it, since all of us had not performed in ten months. When I first emailed the company to inquire about the distancing rules and health regulations for the pit, the entire plan was in my inbox, with pictures, within 24 hours. So that’s the desire, right? They are ready. This is what we’re going to do, and it’s important to us. Companies in Australia that are still going strong, the Finnish National Ballet, the OOTA, which is commissioning works, the Saskatoon Symphony – it’s companies like these that will show us the way. The positive, don’t-stop-moving attitude, that is the way to go.

Lydia Perović is an arts journalist in Toronto. Send her your art-of-song news to artofsong@thewholenote.com.