Remembering Norma Beecroft (1934-2024)

BEECROFT, NORMA MARIAN: It is with deep sadness that we announce the passing of Norma Marian Beecroft in her 91st year, peacefully on Saturday, October 19, 2024. … A beloved Canadian composer, electronic music pioneer, and trailblazer in the world of modern music. Norma’s legacy will continue to resonate through her groundbreaking compositions, the artists she inspired, and the profound impact she had on Canadian music. Norma had an unwavering commitment to supporting young composers and musicians, many of whom cite her as a mentor and inspiration. A celebration of life will be held on Saturday, November 16, 2024 … In lieu of flowers, donations to the Canadian Music Centre, (CMC) in memory of Norma Beecroft, would be especially appreciated by the family.

BEECROFT, NORMA MARIAN: It is with deep sadness that we announce the passing of Norma Marian Beecroft in her 91st year, peacefully on Saturday, October 19, 2024. … A beloved Canadian composer, electronic music pioneer, and trailblazer in the world of modern music. Norma’s legacy will continue to resonate through her groundbreaking compositions, the artists she inspired, and the profound impact she had on Canadian music. Norma had an unwavering commitment to supporting young composers and musicians, many of whom cite her as a mentor and inspiration. A celebration of life will be held on Saturday, November 16, 2024 … In lieu of flowers, donations to the Canadian Music Centre, (CMC) in memory of Norma Beecroft, would be especially appreciated by the family.

‘We can’t think about contemporary music in Canada without thinking of Norma Beecroft. With her passing this week at 90, we’re reminded how, in these moments, an artist becomes the sum of every chapter they’ve written. Norma was a true force in adventurous music …. She knew that detailed, artful compositions – lovingly crafted and meticulously performed – could unlock entirely new worlds for any audience.

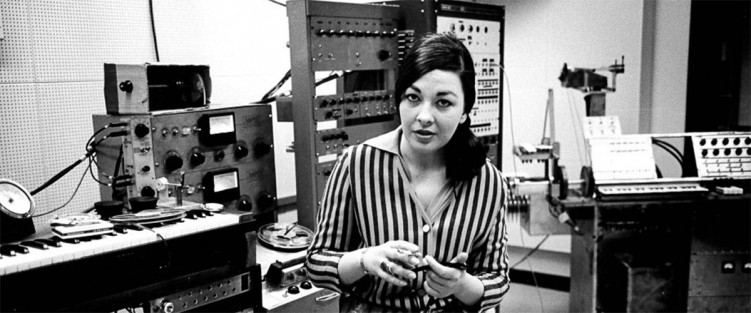

Her innovative spirit continues to inspire, most especially in her pioneering work with electronic music, which she began exploring in the 1960s. There are captivating photos of her in her early 30s in the University of Toronto Electronic Music Studio surrounded by the seemingly magical equipment of the time, an exciting maze of buttons, knobs, and tangled wires. In 1967, this was cutting-edge technology—large machines that allowed composers to manipulate sound in ways never heard before, and a stark contrast to the sleek, digital tools we use today.