Michael Snow, artist-at-large

Sorry, but I’m going to have to skip over much of Toronto-born artist Michael Snow’s vast and diverse body of work, including milestone experimental films, sculptures, paintings, prints, photographs, holographs, slide projections, videos, books and recordings (78, LP, cassette, CD, streaming), among other media. While primarily highlighting his lesser-known career in live music, I’d be remiss if I didn’t first mention a few of his large scale Toronto public artworks.

Perhaps like countless thousands you’ve walked past Michael Snow’s 1989 confrontational gold-painted fibreglass sculpture suite The Audience mounted on the brutalist concrete face of Toronto’s Rogers Centre.

Or you’ve gazed up at Flight Stop, the 1979 site-specific sculptural-photographic work hanging from the ceiling in the Eaton Centre shopping mall. Appearing to depict a flock of some 60 Canada geese whiffling in for a landing, each styrofoam and fibreglass goose is actually enrobed in a photographic sheet, the image taken from a single goose. This dynamic work evocatively freezes indoors an iconic outdoor Canadian aerial migratory event, while also confronting viewers’ preconceptions of photographic illusion.

Then there was the controversy around his Walking Woman, first exhibited in 1962 at Toronto’s Isaacs Gallery. This iconic stylized female silhouette appeared in many guises and in many locations afterwards. A multiple highly reflective stainless steel version was featured in the Ontario Pavilion at Montreal’s Expo 67. The figure could be perceived variably as a presence to be looked at, or an absence to be looked through, manifesting the sort of duality that was a guiding principle in Snow’s work.

Michael Snow, jazz pianist

But before any of these public projects, came music. A self-taught pianist, the teenage Snow began by improvising on blues and jazz standards. In 1948 he cut several 78RPM recordings of them. (There’s a covert jazz connection even in Snow’s Walking Woman, supposedly modelled on his friend and fellow jazz musician Carla Bley.)

Snow graduated to gigging as a pianist in downtown Toronto’s first smoky jazz clubs, a scene Don Owen evocatively captured in his 1963 NFB film Toronto Jazz. We see Snow in action on the piano bench, in his artist studio and on the street carrying his Walking Woman.

Right to the end, Snow’s enthusiasm for Jelly Roll Morton, Earl Hines, boogie and Thelonious Monk bubbled just under his fingers, though it had long since evolved into an elegant, richly multilayered idiosyncratic pianism. “Of course I always wanted to have my own style,” he acknowledged in a 2019 interview, “Free playing makes that more achievable than playing tunes and variations on them.”

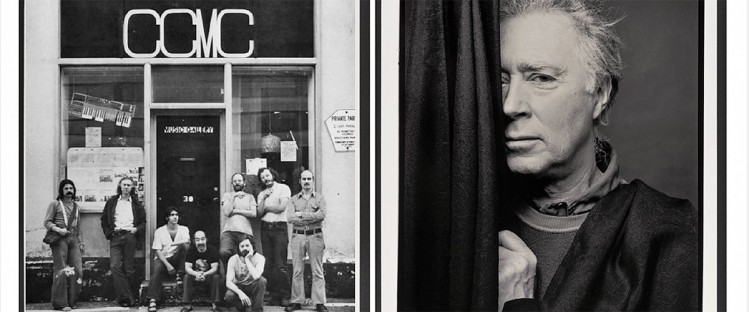

Moving to the Big Apple for the better part of the 60s, his film New York Eye and Ear Control (1964) was an important document of free jazz’s formative stage. On his return to Toronto, Snow brought that musical approach with him, sharing it with his jazz and artist colleagues here. In 1976 it was manifested in the foundation of the ensemble CCMC, which opened The Music Gallery the same year.

Yet when asked in 2014 who his favourite composer/musician was, his (perhaps not so) surprising reply was “J.S. Bach.”

Meet Mr. Snow

Those who met Michael (Mike to some) can attest to his witty, affable, down-to-earth nature, an unlikely set of attributes for such an iconoclastic artist. Michael was invariably collegial with me. And the more I got to know him, the more I appreciated his insatiable artistic curiosity and musical creativity. The latter was on full display both in abstract musical thinking and in practical musicianship which often sparked into virtuosity in his piano playing.

Michael Snow Memorial

To celebrate the man and his career The Music Gallery and Array Music presented Michael Snow Memorial on January 26 at Toronto’s 918 Bathurst Street Centre. I arrived on a crisp ice-glazed night to find an expectant full house, abuzz with all the earmarks of a community celebration.

It proved to be an evening full of smiles, fistbumps, handshakes, hugs and “How are you?” greetings of friends I hadn’t seen in years. Snow’s long and deep genre-leaping career had the power few others can boast: to bring Toronto’s disparate arts communities together under one roof. Snow – who when questioned in 2014 about the meaning of art, responded “shared experience” – would have loved it.

Music critic/author Robert Everett-Green set the tone for the evening. Addressing the audience, he sited Snow’s vast interdisciplinary career in its biographical context, reminding us that when it came to his musical art Snow believed “musical improvisation was composition in real time.” Rather than working from a prepared score like most composers do, he chose early on to work musically outside the box, through improvisation.

An insightful eight-minute tribute video In Memory of Michael Snow followed. Made by Laurie Kwasnik, it featured a montage of excerpts of Snow’s brilliant piano performances going back to the 50s and 60s, capped by later scenes spanning some four decades of him with CCMC. Judging from those clips, few can doubt his awesome keyboard skills and decisive real-time musical thinking.

At one point in the film the senior Snow gingerly walks down the stairs. Cracking a modest smile he says softly, “This is a variation of Duchamp’s painting Nude Descending a Staircase, in this case Clothed Man Descending a Staircase.” His wry reference to Marcel Duchamp’s once-scandalous 1912 modernist painting appears to be an adlib.

The brief scene underlines how central humour was to his approach to life and art. This likeable quality was amply reflected in Snow’s responses to the Marcel Proust questionnaire posed by the National Art Gallery of Canada in 2014. Best quality? “Funny” was Snow’s reply.

CCMC takes the stage

It wouldn’t be much of a Snow celebration without a performance by CCMC, the Toronto group he cofounded and loyally championed for 46 years. It began with an impressive solo by CCMC co-founding musician Nobuo Kubota, featuring his flexible voice which he garnished with clave accents and musical counterpoint emanating from a Cracklebox, a mini synth which fits in the palm of the hand. The sombre mood he established was then undercut by the sudden introduction of a (hopefully plastic) toy strike hammer Kubota struck against the side of his head. Producing a startling percussive sound, the Noh-like theatrical effect was particularly appreciated by children in the front rows.

The CCMC this evening consisted of six musicians, both original and newer members. In addition to Kubota, John Oswald (sax), Al Mattes (electric bass), Paul Dutton (voice, harmonica, emcee), John Kamevaar (electronic drums) and Mani Mazinani (CAT synth) performed. Pianist Casey Sokol was unable to join in due to ill health. In performance, the current CCMC didn’t offer any audible sign of advancing age or dimming of the collective musical power that has marked it as the city’s longest-lived free improv ensemble.

With both original CCMC keyboardists missing, the grand piano fallboard stayed silently closed for the evening.

Personal Memories

For five years beginning in the fall of 1977, I spent long start-up hours working in the Musicworks magazine office on the second floor of the first Music Gallery. CCMC played downstairs twice a week, every week. During the day there was often an open jam. On occasion I’d join in. Sometimes jazz musicians from Snow’s NYC days dropped in. Snow rarely missed a gig, so there was plenty of opportunity to hang and talk (music) shop.

By the 1990s I began to develop my Indonesian suling playing in free improv directions and Michael invited me to play with CCMC a couple of times. He mailed a cassette dub of the first concert, along with a handwritten letter encouraging me to keep playing. It was an unexpected, characteristically generous gesture.

Legacies

I last met Michael and his partner Peggy Gale in November 2019, sitting beside Toronto composer John Beckwith at Array Music’s Udo Kasemets @ 100 concert. I was invited to play suling in SUliNgFLOWER, a work Udo wrote for me. They sat in the front row, paying tribute with their presence to their older friend who’d fearlessly blazed Toronto’s mid-century avant-garde music scene.

Snow’s and Beckwith’s careers, while taking markedly different paths, both emerged from Toronto’s percolating mid-century cultural scene, growing from the same fertile musical soil as say, Glenn Gould. To me, one was the ever-questioning improvising musical iconoclast and maker of cheeky public art, the other the very model of an academic composer.

Was “Michael Snow … the most important artist Canada has produced,” as filmmaker Bruce Elder boldly averred in 2009? Well, I, for one, find it impossible to overestimate his work.

Snow’s art investigated the endless wonder of seeing and hearing, and often found the inherent humour within its frustrations and joys. Often it came down to savouring beauty and wonder in the simplest things around us, like the repeated snapping of a window curtain in the breeze in a recent Snow video.

I ran into him at Toronto openings and concerts, well into his 90s – there because he was genuinely interested. “Art is shared experience,” he might remind us still.

Andrew Timar is a Toronto musician, composer and music journalist. He can be contacted at worldmusic@thewholenote.com.