During a particularly compelling moment in the Art of Time Ensemble’s recent performance, Dance to the Abyss: Music From The Weimar Republic, the ensemble, now in its final season, performed Cab Calloway’s Minnie the Moocher five times in a row. Utilizing a set of detailed instructions from a document titled Nazi Germany’s Dance Band Rules and Regulations, the ensemble uses each rendition to iteratively strip away the lifeblood and very essence of what makes that great 1931 song so paradigmatically part of the jazz of swing-era Harlem.

During a particularly compelling moment in the Art of Time Ensemble’s recent performance, Dance to the Abyss: Music From The Weimar Republic, the ensemble, now in its final season, performed Cab Calloway’s Minnie the Moocher five times in a row. Utilizing a set of detailed instructions from a document titled Nazi Germany’s Dance Band Rules and Regulations, the ensemble uses each rendition to iteratively strip away the lifeblood and very essence of what makes that great 1931 song so paradigmatically part of the jazz of swing-era Harlem.

In the Art of Time’s skilled musical hands, the song metamorphoses (and I mean this in the most Kafkaesque of ways) into something more Joseph Goebbels-approved propaganda, than Lennox Avenue swing.

Far from being repetitive, the successive iterations exemplify the adage death by 1,000 cuts; the ten rules gradually purge any vestige of Black, Jewish and American influence from a piece that the Nazis would have classified as “degenerate art.”

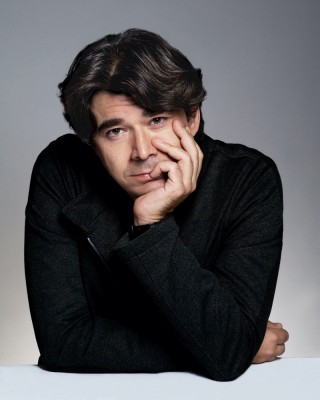

In many ways, the piece epitomized the sort of work that only The Art of Time Ensemble could successfully pull off. Programmed immediately before the show’s intermission, the selection evoked a set of conflicting emotions – darkly funny, of course, but also horrifyingly revelatory of how easily a vibrant musical form could be, and was, co-opted for nefarious fascistic purposes. But conflicting emotions are the point. Dance to the Abyss is like so much of the work that Art of Time, under the able leadership of pianist and Artistic Director Andrew Burashko, has done with consistent aplomb over its 25-year history. It is a performance-based challenge to the audience, designed to make one both listen with intentionality, and think.

“One of the things that I’ve been most interested in these last 25 years is to offer as mixed and eclectic a program as possible,” states Burashko, reflecting upon the expanse of work that the group has done since its inception in 1998: pairing the compositions of contemporary American jazz pianist Joey Calderazzo with the lieder of Richard Strauss; reimagining Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band with a cast of musicians comprised of this country’s finest jazz, classical, and pop players; or finally, the ensemble’s upcoming May 2024 tribute to Joni Mitchell in Both Sides Now. Fusion, hybridity and a purposeful attempt to reside in the musical margins, defying classification, have been the raison d’etre for both Art of Time, and Burashko for a quarter century.

The swamp of human desire: Burashko garnered an initial reputation at age 17, when he made his debut with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra as a classical pianist of note, immersed in the standard concertizing repertoire that the role demands. As he explained to me, however, he soon became interested in “exploring where high art, for lack of a better term, intersects with popular culture.” Many previous Art of Time presentations have mined this intersection – Burashko cites Igor Stravinsky’s Ebony Concerto, which the Russian composer wrote for Woody Herman’s First Herd, or Dmitri Shostakovich’s Jazz Orchestra Suites. But it is Berlin’s cabaret scene of the late 1920s in Dance to the Abyss that perhaps best exemplifies this fusion.

“I was always fascinated with the richness of that scene” Burashko states. “I love Kurt Weill, Erwin Schulhoff and the composers of that era. Plus, the Dadaists like Kurt Schwitters, writers such as Franz Kafka and Thomas Mann, and the Berlin Cabaret which contributed to what at the time was a swamp of unfettered human desire.”

The challenge here, as with any Art of Time show, is how to navigate the swamp rather than just describe it, especially when you eschew traditional program notes. How does one convey the context and the story behind the music through the music itself? “How does one make it both rigorously historically accurate, and compelling enough to offer audiences an entry point into the incredible 400 years of history and music that we today call classical?” wonders Burashko.

That question, coming from the Art of Time’s director in 2024, is, of course, rhetorical. Presenting challenging, disparate music to audiences in a cohesive manner that combines dramaturgy, spoken word, humour, historical narration and stylistic intersection is exactly the sort of thing that the pianist and his ensemble have long since figured out how to do. A big part of that, and of the Art of Time’s longevity and success more generally, is defying the strict performance practices that reigned supreme in classical music during the 20th century. “When the Art of Time started,” states Burashko, “the idea of someone talking and breaking through the fourth wall was almost never done. But I have always wanted to speak to, engage with, and entertain the audience; I have had no interest in the ‘this is our offering, take it or leave it’ approach to concert presentation.”

Dismantling: Whether Art of Time was a harbinger of change or the beneficiary of fortuitous timing, things in the classical music world “have changed considerably over the last 25 years,” Burashko says. As evidence, he points out that today, even the august and renowned pianist András Schiff concertizes with a clip-on Lavalier microphone, addressing his audience from the stage between works, something that would have been anathema even a few years earlier.

What, discovered during Art of Time’s inaugural 1999 season (listed originally as Chamber Music Unlimited), was that the bringing together of disparate music (Cage, Gershwin, Crumb, and Lieberson) in combination with dance, evocative staging, and thoughtful on-stage commentary (modest initially, but expanded throughout the seasons), constituted a gradual dismantling of the restrictive traditions of the art form – an intoxicating elixir for an audience hungry for a welcoming entry point into a world of great music.

“It still amazes me: I would meet people who said they don’t know how to listen to classical music or even what makes it good,” continues Burashko. “But music should elicit a visceral reaction. And while I’m happy if people walk away [from an Art of Time Ensemble performance] having learned something, I first and foremost want to turn people onto this great music.”

As much as Burashko’s now well-honed skills as a raconteur, presenter of ideas, and a setter of appropriate performance contexts now appear effortless, these were, of course, a set of skills that he had to develop along the trajectory of the ensemble’s life. “It has been an incredible ride,” he acknowledges. “When Art of Time started, I was strictly a concert pianist. But since then, who knows how many hours I’ve spent conducting, staging, directing and producing. And now, the whole curation thing has really become a part of me with things unfolding in a way that I could not have predicted.”

Hierarchical inevitability: With a nod to the inevitability of hierarchical career trajectories that promote competent people into opportunities requiring an entirely different set of skills from those they had mastered in their previous position, the success of Art of Time has meant a necessary move away from what initially attracted Burashko to a career in music in the first place. “It’s funny,” he says, expanding upon this point. “The more successful the organization became, the more I’ve had to compete with the machine that surrounds it and now overshadows the art. I am just tired of everything that goes into running an organization that has nothing to do with the art itself. The fundraising and the organizing. It all requires so much energy. And, well, life is short, and I just want to play, for lack of a better word.”

Whether it was the pivotal pause-to-reflect that the COVID lockdowns of the early 2020s unexpectedly bestowed, or the opportunity that a 25th anniversary affords to tie a nice bow on things, this has been announced as the Art of Time’s coda season. Burashko is quick to point out that he is not “hanging up the brand,” citing such upcoming projects as an animated film capture of the aforementioned Minnie the Moocher performance titled Jackboots to Jazz, a Sgt. Pepper’s Ontario summer tour, a Shakespeare show at Stratford, and, finally, a creative reimagining of Igor Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale in October (complete with a newly commissioned libretto).

And yet, despite all of this, there is something conclusionary about the feel of this season. “We have over 80 projects in our back pocket, at least a dozen of which I would love to see given some kind of life, so I’m hoping there will be more touring. But, in terms of what’s next, I honestly don’t have a clue. And, quite frankly, I’m finding that very exciting.”

The Art of Time’s presentation of Both Sides Now will run from May 9 to 11 at Toronto’s Harbourfront Centre.

Andrew Scott is a Toronto-based jazz guitarist (occasional pianist/singer) and professor at Humber College, who contributes regularly to The WholeNote Discoveries record reviews.