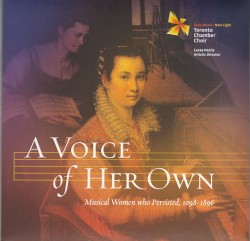

A Voice of Her Own: Musical Women Who Persisted 1098-1896 - Toronto Chamber Choir; Lucas Harris

A Voice of Her Own – Musical Women Who Persisted 1098-1896

A Voice of Her Own – Musical Women Who Persisted 1098-1896

Toronto Chamber Choir; Lucas Harris

Independent n/a (torontochamberchoir.ca)

Sacred and secular music require two wholly different mindsets and the singers of the Toronto Chamber Choir, with Lucas Harris as artistic director, have the wherewithal to do both in spades. Both genres demand an immersion of sorts into the music itself. The performance by this choir does more than simply tick all the boxes; it soars impossibly high, taking the music to another realm altogether. Another challenge – admirably handled by the choir – is the fact that the music spans almost 800 years of evolved tradition.

The program itself is an inspired one and is quite representative of women composers who, as the title suggests, emerged with high honours in a world dominated, at every level of art and its commerce, by men. This recording gets off to a glorious start with music by the ecstatic mystic, Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179). In the extract from Ordo Virtutum, where the monastic nun adapted the language of visions and of religious poetry, the choir’s interpretation is resonant and retains the exquisite purity of the music.

From the soaring intensity of the anonymous 17th-century composition Veni, sancte Spiritus by the nuns of Monastère des Ursulines de Québec through songs from Gartenlieder by the prodigiously gifted Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel (1805-1847) to the deep melancholia of Clara Schumann’s (1819-1896) work, the musicians and choristers achieve unmatched levels of elegance and refinement.