The Montreal-based cellist Elinor Frey is back with a second volume of premiere recordings of works by the cellist-composer Giuseppe Clemente Dall’Abaco (1710-1805!) on The Cello According to Dall’Abaco, accompanied by Catherine Jones (cello), Federica Bianchi (harpsichord) and Michele Pasotti (theorbo) (Passacaille PAS 1122 elinorfrey.com).

The Montreal-based cellist Elinor Frey is back with a second volume of premiere recordings of works by the cellist-composer Giuseppe Clemente Dall’Abaco (1710-1805!) on The Cello According to Dall’Abaco, accompanied by Catherine Jones (cello), Federica Bianchi (harpsichord) and Michele Pasotti (theorbo) (Passacaille PAS 1122 elinorfrey.com).

Frey’s critical edition of the 35 accompanied cello sonatas of Dall’Abaco is published by Walhall Editions; five sonatas were featured on the first CD (PAS 1069) and a further three – in G Major ABV28, E-flat Major ABV37 and D Minor ABV45 – are heard here, together with all three of Dall’Abaco’s cello duets: the Duetto in G Major ABV47, the Duo in F Major ABV48 and the Duo in A Minor ABV49. No composition dates are known, but the music is probably from the 1730-1750 period.

The second cello adds depth to the continuo in the sonatas, while in the quite lovely duos the roles of melody and accompaniment are continually exchanged between the two performers.

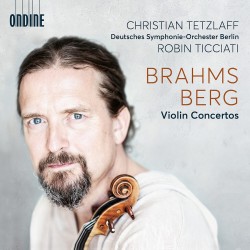

Violinist Christian Tetzlaff cites “reasons of substance” to justify pairing the Brahms & Berg Violin Concertos on his latest CD, with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin under Robin Ticciati, both works searching the depths of the soul and having a lot to say about pain (Ondine ODE-1410-2 ondine.net).

Violinist Christian Tetzlaff cites “reasons of substance” to justify pairing the Brahms & Berg Violin Concertos on his latest CD, with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin under Robin Ticciati, both works searching the depths of the soul and having a lot to say about pain (Ondine ODE-1410-2 ondine.net).

Tetzlaff has been playing both concertos for 40 years for a combined total of over 300 performances, and it shows. The Brahms is immensely satisfying, but the real joy here is the Berg, long recognized not only as a requiem for the 18-year-old Manon Gropius but also for Berg himself, the composer dying just four months after finishing the work. Moreover, the concerto is a deeply personal autobiography, full of intimate details of Berg’s life – tellingly, Tetzlaff’s detailed booklet essay is almost entirely about the Berg and its inner references. This is a performance by someone who knows this work inside out, and who finds the Bach chorale ending “incredibly beautiful whenever I play it.” And so it is.

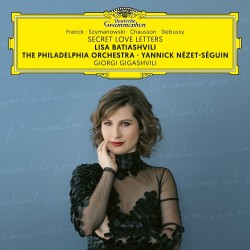

Secret Love Letters, the latest CD from violinist Lisa Batiashvili celebrates the concealment of the message of love in music, noting that so much of the message is secret and intimate (Deutsche Grammophon 00028948604623 lisabatiashvili.com/).

Secret Love Letters, the latest CD from violinist Lisa Batiashvili celebrates the concealment of the message of love in music, noting that so much of the message is secret and intimate (Deutsche Grammophon 00028948604623 lisabatiashvili.com/).

Pianist Giorgi Gigashvili joins the violinist in an electrifying performance of the Franck Sonata in A Major. Batiashvili’s shimmering tone and strength in the highest register are fully evident in Szymanowski’s Violin Concerto No.1 Op.35 with its gorgeous and heart-rending main theme, the Philadelphia Orchestra under Yannick Nézet-Séguin providing the accompaniment here and in Chausson’s Poème Op.25, originally called Le Chant d’amour triumphant.

Nézet-Séguin is the pianist for the Heifetz arrangement of Debussy’s Beau soir which ends a CD that adds to Batiashvili’s already impressive discography.

The Big B’s, the third CD from the fabulous Janoska Ensemble of Bratislava-born Janoska brothers Ondrej and Roman on violin and pianist František, with brother-in-law Julius Darvas on bass, features music by Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Bartók, Bernstein and Brubeck, all delivered in the inimitable virtuosic and semi-improvisational Janoska style (Deutsche Grammophon 00602445962075 deutschegrammophon.com/en/catalogue/products/the-big-bs-janoska-ensemble-12750).

The Big B’s, the third CD from the fabulous Janoska Ensemble of Bratislava-born Janoska brothers Ondrej and Roman on violin and pianist František, with brother-in-law Julius Darvas on bass, features music by Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Bartók, Bernstein and Brubeck, all delivered in the inimitable virtuosic and semi-improvisational Janoska style (Deutsche Grammophon 00602445962075 deutschegrammophon.com/en/catalogue/products/the-big-bs-janoska-ensemble-12750).

The Bach Double Violin Concerto in D Minor BWV1043 sees the second violin take an improvised jazz approach. Two violins intertwine beautifully in the slow movement from Beethoven’s Pathétique Piano Sonata, and Brahms’ Hungarian Dance No.1 is a blast, as are Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances. There’s great piano in the Brubeck Blue Rondo à la Turk and superb ensemble in Bernstein’s Candide Overture.

There are four original pieces inspired by the brothers’ children, and the CD ends with František’s riotous Beethoven paraphrase of Nine Symphonies in Nine Minutes. Wonderful violin playing and terrific piano anchor a dazzling CD which is a pure delight from start to finish.

It’s hard to imagine more appropriate performers for a Dvořák string quartet recital than a top Czech ensemble, feelings more than borne out by listening to the Talich Quartet, originally formed in 1964 on their latest CD Dvořák American Quartet & Waltzes, their first recording with their new lineup (La Dolce Vita LDV101 ladolcevolta.com/?lang=en).

It’s hard to imagine more appropriate performers for a Dvořák string quartet recital than a top Czech ensemble, feelings more than borne out by listening to the Talich Quartet, originally formed in 1964 on their latest CD Dvořák American Quartet & Waltzes, their first recording with their new lineup (La Dolce Vita LDV101 ladolcevolta.com/?lang=en).

The Eight Waltzes for Piano Op.54 B101 date from 1879-80; two were transcribed for string quartet by the composer himself, with the remaining six being transcribed for the Talich Quartet in 2020 by violist Jiří Kabát. They are an absolute delight.

The Quartet Movement in F Major B120 from October 1880 was intended as the first movement of a new quartet but abandoned; not premiered until 1945, it was published in 1951.

A beautifully warm performance of the String Quartet in F Major Op.96 B179 “American” that simply bursts with life and spontaneity closes an outstanding CD.

The wonderful Steven Isserlis is back with another engrossing CD, this time celebrating a period which saw a huge expansion in the cello and piano repertoire on A Golden Cello Decade 1878-1888 with Canadian pianist Connie Shih (Hyperion CDA68394 hyperion-records.co.uk/dc.asp?dc=D_CDA68394).

The wonderful Steven Isserlis is back with another engrossing CD, this time celebrating a period which saw a huge expansion in the cello and piano repertoire on A Golden Cello Decade 1878-1888 with Canadian pianist Connie Shih (Hyperion CDA68394 hyperion-records.co.uk/dc.asp?dc=D_CDA68394).

Bruch’s Kol Nidrei Op.47 from 1881 opens the disc, the sumptuous richness of Isserlis’ 1726 “Marquis de Corberon” Strad heard to full effect. Olivia Jageurs adds the harp part.

The 15-year-old Richard Strauss and the 30-year-old German composer Luise Adolpha Le Beau both submitted cello sonatas to an 1881 competition, but neither won. At least Le Beau had her Sonata in D Major Op.17 published, but Strauss withdrew his Sonata in F Major Op.6 and rewrote it in 1883; the original sonata heard here was finally published in 2020. Le Beau’s 1878 sonata is a rarely heard gem, and deserves to be much better known.

Dvořák’s 4 Romantic Pieces Op.75 from 1887 are heard in an arrangement by Isserlis, and two Footnotes close the disc: Ernst David Wagner’s Kol Nidrei and Isaac Nathan’s Oh! weep for these, the melody used in the second part of Bruch’s Kol Nidrei.

Shadows, the new CD from cellist Lorenzo Meseguer and pianist Mario Mora features works by Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn, Clara Schumann and Gustav Jenner, the connection apparently being “people living in the shadow of other composers” (Eudora EUD-SACD-2204 eudorarecords.com).

Shadows, the new CD from cellist Lorenzo Meseguer and pianist Mario Mora features works by Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn, Clara Schumann and Gustav Jenner, the connection apparently being “people living in the shadow of other composers” (Eudora EUD-SACD-2204 eudorarecords.com).

Certainly Fanny and Clara were overshadowed by their brother and husband respectively, and Jenner, Brahms’ only compositional student clearly qualifies, but it’s an extremely tenuous link to Felix, who seems to be regarded here as under-appreciated more than overshadowed.

No matter, for there’s so much to enjoy and admire on this disc, from Fanny’s lovely but infrequently performed Fantasia in G Minor through Felix’s Sonata No.2 in D Major Op.58 – its really tricky passage-work in the Molto Allegro e vivace finale handled superbly – to Clara’s Drei Romanzen Op.22 (originally for violin and piano and transcribed here by the duo) and Jenner’s unsurprisingly quite Brahmsian Sonata in D Major.

Fine, rich playing and a beautifully full, clean and resonant recording make for a quite outstanding CD.

On Bridge/Britten: Viola Works the violist Hélène Clément plays the 1843 Francesco Giussani viola, on loan from Britten Pears Arts that was owned by Frank Bridge and gifted by him to Benjamin Britten in 1939, calling the CD “a testament to both composers and the instrument that binds them all together.” She is accompanied by pianist Alasdair Beatson (Chandos CHAN 20247 chandos.net/products/catalogue/CHAN%2020247).

On Bridge/Britten: Viola Works the violist Hélène Clément plays the 1843 Francesco Giussani viola, on loan from Britten Pears Arts that was owned by Frank Bridge and gifted by him to Benjamin Britten in 1939, calling the CD “a testament to both composers and the instrument that binds them all together.” She is accompanied by pianist Alasdair Beatson (Chandos CHAN 20247 chandos.net/products/catalogue/CHAN%2020247).

Bridge’s Cello Sonata in D Minor from 1913-17 is heard here in Clément’s arrangement for viola. There is a Willow Grows aslant a Brook: Impression for Small Orchestra from 1927 was arranged for viola and piano by Britten in 1932. Mezzo-soprano Dame Sarah Connolly is the soloist in the Three Songs for Medium Voice, Viola and Piano from 1906-07, not published until 1982.

The two Britten works are the 1930 Elegy for Solo Viola and the Lachrymae: Reflections on a Song of Dowland Op.48 from 1950, revised in 1970.

The knowledge that both composers played this instrument and would have had its sound in mind when writing for viola certainly adds to the impact of an excellent CD.

The CD Ondulation: Bach & Kurtág features outstanding playing by guitarist Pedro Mateo González (Eudora EUD-SACD-2202 eudorarecords.com).

The CD Ondulation: Bach & Kurtág features outstanding playing by guitarist Pedro Mateo González (Eudora EUD-SACD-2202 eudorarecords.com).

The three Bach works are the Lute Suite in C Minor BWV997, the Cello Suite in G Major BWV1007 and the Violin Partita No.2 in D Minor BWV1004. The Lute Suite is rhythmically bright, with crystal-clear ornamentation; the Cello Suite is sensitive and quite beautiful. There are some added bass notes and the occasional filling out of chords in the Partita, and brilliant clarity in the rapid runs in the challenging Chaconne.

First recordings of four extremely brief pieces from the Darabok a Gitáriskolának by the Hungarian composer György Kurtág (b.1926) act as interludes between the Bach works. González is technically flawless, with a superb sense of line and phrase. With its beautifully clean playing and recording it’s as fine a guitar CD as I’ve heard lately.

Yuri Liberzon is the guitarist on Konstantin Vassiliev Guitar Works 1, a recital of works by the Russian-born German composer that merge jazz, Russian folk music and contemporary Western trends in beautifully-crafted and entertaining short pieces (Naxos 8.574315 naxos.com/Search/KeywordSearchResults/?q=8.574315).

Yuri Liberzon is the guitarist on Konstantin Vassiliev Guitar Works 1, a recital of works by the Russian-born German composer that merge jazz, Russian folk music and contemporary Western trends in beautifully-crafted and entertaining short pieces (Naxos 8.574315 naxos.com/Search/KeywordSearchResults/?q=8.574315).

One piece here – Fatum – is from 1996, with the remaining 11 composed between 2005 and 2019; three were written specifically for Liberzon. There are some fascinating and innovative percussive effects in the bossa nova-inspired Hommage à Tom Jobim, and some lovely melodic writing in numbers like Cavatina and Rose in the Snow. Patrick O’Connell, Liberzon’s partner in the Duo Equilibrium is the second guitarist on Obrío and on the Two Russian Pieces that close the disc.

Recording quality, produced and edited by Norbert Kraft at St. Paul’s Anglican Church in Newmarket, Ontario is of the usual top-notch Naxos level.

Two elegiac piano trios honouring the memory of a close friend are featured on Elegie, the new CD from Trio Arriaga (Eudora EUD-SACD-2201 eudorarecords.com).

Two elegiac piano trios honouring the memory of a close friend are featured on Elegie, the new CD from Trio Arriaga (Eudora EUD-SACD-2201 eudorarecords.com).

Tchaikovsky’s Piano Trio in A Minor Op.50 was composed in late 1881, the March 1882 premiere marking the first anniversary of the death of pianist Nikolai Rubinstein, founder of the Moscow Conservatory. It’s a large work with an interesting structure – a lengthy and rhapsodic opening Pezzo Elegiaco followed by an even longer Tema con variazioni, with virtuosic piano writing throughout.

Shostakovich’s 1944 Piano Trio No.2 in E Minor Op.67 was in memory of the death of Ivan Sollertinsky, artistic director of the Leningrad Philharmonic. More than a lament for a lost friend, the work also reflects the growing awareness of the Nazi wartime atrocities.

There’s outstanding playing and ensemble work throughout an excellent CD.

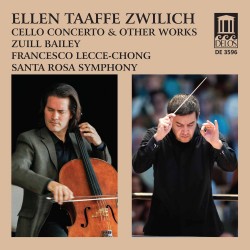

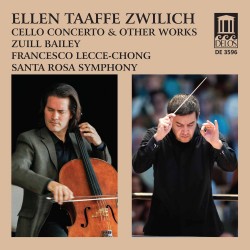

During the pandemic lockdown the Santa Rosa Symphony under Francesco Lecce-Chong presented a series of live concerts recorded for a virtual audience, with Ellen Taaffe Zwilich the featured composer. The new CD Ellen Taaffe Zwilich Cello Concerto & Other Works is devoted to works that were performed during those concerts (Delos DE 3596 delosmusic.com).

During the pandemic lockdown the Santa Rosa Symphony under Francesco Lecce-Chong presented a series of live concerts recorded for a virtual audience, with Ellen Taaffe Zwilich the featured composer. The new CD Ellen Taaffe Zwilich Cello Concerto & Other Works is devoted to works that were performed during those concerts (Delos DE 3596 delosmusic.com).

The Cello Concerto from 2019-20 is performed by Zuill Bailey, for whom it was commissioned. The third of its three fairly short movements in particular exploits the singing, lyrical nature of the instrument.

Elizabeth Dorman is the soloist in Peanuts® Gallery for Piano and Orchestra, six short pieces written in 1996 on commission for a Carnegie Hall children’s concert and featuring characters from the Charles Schulz cartoon strip.

Violinist Joseph Edelberg brings a warm, rich tone to the quite lovely 1993 Romance for Violin and Chamber Orchestra, and the Prologue and Variations for String Orchestra closes an entertaining disc.

Micro-Nap

Micro-Nap