Review: “Parry: Songs of farewell” - sacred English music, sung with subtle sensitivity

![]() This article appears in The WholeNote as part of our collaboration in the Emerging Arts Critics program.

This article appears in The WholeNote as part of our collaboration in the Emerging Arts Critics program.

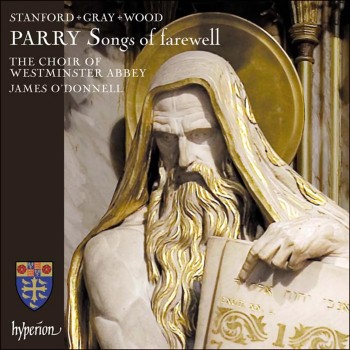

Parry: Songs of farewell & works by Stanford, Gray & Wood

Parry: Songs of farewell & works by Stanford, Gray & Wood

Westminster Abbey Choir, James O'Donnell (conductor)

Hyperion CDA68301

Parry: Songs of farewell & works by Stanford, Gray & Wood, the Westminster Abbey Choir’s latest offering on the Hyperion label, brings together in death two composers often fiercely at odds in life: the sometimes-friends, sometimes-rivals Hubert Parry and Charles Villiers Stanford. As English choral composers working at the turn of the 20th century and colleagues at the Royal College of Music, the two alternately championed and criticized each other’s work. In pairing these two artists’ late-career compositions with selections from their lesser-known contemporaries Charles Wood and Alan Gray, the Westminster Abbey Choir has created a fascinating conversation on visions of life, death, and eternity within the English sacred music tradition, shaped by four composers experimenting and excelling in the genre. The all-boys Abbey Choir interprets with sensitivity both the subtlety and grandeur of these compositions, and I found myself listening to excerpts again and again to uncover their detail.

Stanford’s Three Latin Motets open the album. Director James O’Donnell expertly leads the choir through the arc of Justorum animae, the first motet: from resonant exhortation for righteousness, into the ominous warnings of the “trials of evil” with echoing minor repetitions, to a final major-key promise of peace. Coelos ascendit hodie is a triumphal Ascension hymn, with repeated “alleluias” that climb to a jubilant “Amen” at the motet’s majestic conclusion. Beati quorum via is comparatively gentler, a dialogue between overlapping upper and lower voices contrasting two lines from Psalm 119 before resolving in still union.

Stanford was less successful, I think, with his Magnificat for eight-part chorus in B flat. He composed this after reconciling with Parry near the end of Parry’s life, and dedicated it to him in publication (though Parry died before seeing it). Perhaps Stanford was overcompensating in his attempted atonement, but the Magnificat lacks the religious reverence we hear in his Motets. The Magnificat opens with boisterous counterpoint, the choir’s sopranos rapidly ascending and descending in a confusing first stanza. This indulgence is echoed in the doxology, and both sections consequently feel incoherent in their detail. The choir achieves a greater tonal clarity in the middle verses, where Stanford comes closer to the eloquent simplicity typical of the late English choral style. More successful still were the canticles by Alan Gray and Charles Wood, Stanford’s contemporaries at Cambridge. Wood’s Nunc dimittis is especially strong in its varied dynamics; O’Donnell guides the choir through the motet’s ebbing and flowing phrases to the striking Gregorian-inspired doxology.

Though Stanford’s attempted homage to Parry falls short of the mark, Parry’s own valedictory composition of the same time is a comparative triumph. The album’s high point is Parry’s six motets, collectively titled Songs of Farewell. Written shortly before his death in 1918, Parry’s compositions echo the sacred music of this period, but take lyrical inspiration from English poets contemplating life beyond death.

The first four motets move swiftly, dramatic in their rhythmic variation. I was struck by I know my soul hath power to know all things, with its repeated, hesitant “and yet,” a reflection on human frailty. Never weather-beaten sail, with its contrapuntal wanderings, evokes the sailboat on still water at sunset, embarking on life’s final journey. And the wistful There is an old belief is sustained throughout by constant overlapping voices yearning into the upper octaves, fulfilling poet John Gibson Lockhart’s lyrics as the choir reaches “beyond the sphere of grief.”

Each of Parry’s Songs offers an inventive vision, but it is the fifth and sixth motets which I found most moving. The penultimate At the round earth’s imagined corners is Parry’s melodic invention at its richest: the lively motet is mystical in its many voices as the basses recount the resurrection of the dead, and the sopranos in eerie chromaticism sing of beholding God. The choir’s harrowing pleas coalesce in the motet’s last line of prayer, leading us to Parry’s final farewell, Lord let me know mine end, its plaintive text taken from Psalm 39. Here, O’Donnell’s keen sense of silence shapes the motet into a powerful declaration – the mournful echoes of “mine age is as nothing” and “thy heavy hand” hang in chilling, empty space. The choir’s repeated murmuring of the word “fretting” is another delightful moment of dynamics, as with the crescendo in the Psalm’s final plea, “O spare me a little,” with each choral section excelling in clear, bold tones.

Parry reportedly denied that the Songs of Farewell had any significance for the end of his life, but the intimate revelation of each motet suggests his deep contemplation and thematic attention in composition. In seeming to write his own adieu, he reconciled himself with his past and anticipated an unknowable future. It is Parry’s visions of the fearful now and the imagined beyond which will remain active in my memory long after I’ve stopped playing this album on repeat.

The Westminster Abbey Choir with James O'Donnell (conductor) released Parry: Songs of farewell & works by Stanford, Gray & Wood (Hyperion) on May 29, 2020.

Marie Trotter is a Toronto-based writer, avid theatre-goer, and occasional director. She studied Drama and English at the University of Toronto with a focus on directing and production, and recently completed her MA in English Language and Literature at Queen’s University.