Review

If you’re a regular listener to Tom Allen’s Shift program on CBC Radio then you’ve probably already heard two of the tracks from DANZAS, the new CD of Spanish guitar music from MG3, the Montréal Guitare Trio of Glenn Lévesque, Sébastien Dufour and Marc Morin (Analekta AN 2 8791).

By pure coincidence the CD arrived in the mail the same afternoon that Allen played a movement from Agustín Barrios Mangoré’s La Catedral, so I knew how good the CD was going to be before even opening it. And “good” is putting it mildly. From the dazzling flamenco runs and rhythms of the opening track of Al Di Meola’s Mediterranean Sundance and Paco De Lucía’s Rio Ancho, the MG3 return to the Spanish roots of their student days with a program of terrific arrangements of mostly standard works.

In addition to the Mangoré Catedral there are six tracks of dances and songs by Manuel De Falla, De Lucia’s Canción de amor and finally Charlie Haden’s Our Spanish Love Song. All arrangements are by the guitarists, either together or as individual efforts by Dufour or Lévesque. The outstanding playing is beautifully captured in a resonant recording made last October in the St-Benoît-de-Mirabel Church in Québec.

Review

There’s more terrific guitar playing on Mappa Mundi, the new CD with a mixture of old and new works from the Canadian Guitar Quartet of Julien Bisaillon, Renaud Côté-Giguère, Bruno Roussel and Louis Trépanier (ATMA Classique ACD2 2750).

There’s more terrific guitar playing on Mappa Mundi, the new CD with a mixture of old and new works from the Canadian Guitar Quartet of Julien Bisaillon, Renaud Côté-Giguère, Bruno Roussel and Louis Trépanier (ATMA Classique ACD2 2750).

Vivaldi’s Concerto in G Minor for Two Cellos RV531 works extremely well in Roussel’s arrangement, with all four guitarists sharing the two solo lines at some point in the three movements.

The other four works on the CD are all comparatively recent compositions. Fille de cuivre (Copper Girl) by quartet member Côté-Giguère explores the conflicting emotions when outward persona is not matched by inner self; it was inspired by the metal-welding works of Québecois sculptor Jean-Louis Émond, whose sculptures include a woman with a perfectly polished front but an open back revealing the rough inner welds.

Concierto Tradicionuevo by Patrick Roux (b.1962) is a terrific homage to the Argentinian tango, with particular nods to the 1930s singer Carlos Gardel and – in a particularly dazzling movement – Astor Piazzolla.

Octopus, by the German composer Hans Brüderl (b.1959) was originally a work for eight guitars (hence the title pun: Oct-Opus) written for the Canadian Guitar Quartet and the Salzburg Guitar Quartet; the former enjoyed it so much that Brüderl adapted it for four guitars. It’s a delightful piece with a real “Wow!” factor.

The CD’s title work Mappa Mundi was written by the Canadian composer Christine Donkin (b.1976) and is a portrayal of four of the images on the 14th-century world map held at Hereford Cathedral in England. Cellist Rachel Mercer joins the quartet in the Tower of Babel movement, the cello representing the voice of God!

These are all substantial, captivating works, beautifully played and recorded.

Butterflies in the Labyrinth of Silence features the guitar music of the Swiss composer Georges Raillard (b.1957) in performances by the American guitarist David William Ross (Navona Records NV6071). Raillard studied classical guitar and composition in the mid-1970s, and his guitar compositions are available for download through his website at georges-raillard.com.

Butterflies in the Labyrinth of Silence features the guitar music of the Swiss composer Georges Raillard (b.1957) in performances by the American guitarist David William Ross (Navona Records NV6071). Raillard studied classical guitar and composition in the mid-1970s, and his guitar compositions are available for download through his website at georges-raillard.com.

The works here date from 1999 to 2008 and, with titles like Shells on the Beach, Summer Evening at the Rhine, Butterfly and Measuring Clouds, are clearly essentially light classical pieces. Although somewhat limited in technical range in comparison to many contemporary works – often with the feel of classical guitar études – they are consistently pleasant, well-written and competent pieces by someone who clearly loves and understands the instrument. There is lovely clean playing from Ross throughout a thoroughly enjoyable CD.

The Cypress String Quartet celebrated its 20th anniversary and its final season in 2016, and for its final recording in April chose the two String Sextets by Brahms, asking longtime friends and collaborators violist Barry Shiffman and cellist Zuill Bailey to join them (Avie Records AV2294). The performers also opted to make the recordings in front of a live studio audience, although there is no hint of audience presence on the CD.

The Cypress String Quartet celebrated its 20th anniversary and its final season in 2016, and for its final recording in April chose the two String Sextets by Brahms, asking longtime friends and collaborators violist Barry Shiffman and cellist Zuill Bailey to join them (Avie Records AV2294). The performers also opted to make the recordings in front of a live studio audience, although there is no hint of audience presence on the CD.

The Sextets No.1 in B-flat Major Op.18 and No.2 in G Major Op.36 are given simply beautiful performances. Brahms always seems to have that quality of wistfulness and yearning, but the G Major work is particularly appropriate here, Brahms having learned from Robert Schumann the device of using musical notation to denote the names of people in one’s life and consequently turning this work into an emotional farewell to his lost love Agathe von Siebold.

It is hardly surprising then that this work should make such a fitting conclusion to the Cypress Quartet’s career. As the quartet members note, the works were an obvious choice for this final CD: “these monumental String Sextets . . . with their warmth and reflective qualities, are perfectly suited to saying farewell.”

The Cypress Quartet will be greatly missed, but this CD is a wonderful tribute to their talents.

The outstanding French cellist Emmanuelle Bertrand is back with another excellent CD, this time featuring the Cello Concerto No.1 in A Minor Op.33 by Camille Saint-Saëns with the Luzerner Sinfonieorchester under James Gaffigan and also the Cello Sonatas Nos.2 & 3 with Bertrand’s partner, pianist Pascal Amoyel (harmonia mundi HMM 902210).

The outstanding French cellist Emmanuelle Bertrand is back with another excellent CD, this time featuring the Cello Concerto No.1 in A Minor Op.33 by Camille Saint-Saëns with the Luzerner Sinfonieorchester under James Gaffigan and also the Cello Sonatas Nos.2 & 3 with Bertrand’s partner, pianist Pascal Amoyel (harmonia mundi HMM 902210).

Saint-Saëns clearly had a great love for the cello, and it shows throughout these works. Bertrand gives a passionate and convincing performance of the concerto, with excellent orchestral support. Bertrand and Amoyel are, as usual, as one voice in beautifully judged readings of the two sonatas. All of the usual outstanding Bertrand qualities – tone, phrasing, sensitivity and musical intelligence – are here in abundance.

The Sonata No.3 is a late work that occupied the composer from 1913 to 1919, but unfortunately the final two movements have been lost, and the first two exist only in manuscript. This lovely performance is the first recording of the work and leaves us wondering just what we are missing in the two lost movements.

I could easily use an entire column to review Cello Stories – The Cello in the 17th and 18th Centuries, the quite remarkable hardcover book and 5-CD set featuring the French cellist Bruno Cocset and his group Les Basses Réunies, with text by the Baroque cellist and musicologist Marc Vanscheeuwijck (Alpha Classics ALPHA 890).

I could easily use an entire column to review Cello Stories – The Cello in the 17th and 18th Centuries, the quite remarkable hardcover book and 5-CD set featuring the French cellist Bruno Cocset and his group Les Basses Réunies, with text by the Baroque cellist and musicologist Marc Vanscheeuwijck (Alpha Classics ALPHA 890).

Cocset says that the intention is to show how an instrument and its repertoire have taken shape, and he has selected the musical program from his recordings for Alpha – some of them previously unreleased – made between 1998 and 2013. The five discs are: The Origins, with music by Ortiz, Bonizzi, Frescobaldi, Vitali, Galli and Degli Antonii; Italy-France, with music by Marcello, Vivaldi and Barrière; Johann Sebastian Bach, two CDs of cello sonatas, choral preludes, movements from the Cello Suites Nos. 1, 2 and 4 and the complete Suites 3, 5 and 6; and From Geminiani to Boccherini, including a short sonata by Giovanni Cirri.

The book is in English and French, with full track listings and recording details, and there are 15 pages of full-colour contemporary illustrations. The astonishingly detailed and researched text portion on the history and development of the instrument and its playing techniques runs to about 50 pages and has 386 footnotes.

The playing throughout is quite superb. It’s a simply astonishing project, completed in quite brilliant fashion.

Melia Watras: 26 (Sono Luminus SLE-70007) is a fascinating CD inspired by the concept of violists performing and sharing their own compositions. Violists Watras, Atar Arad and Garth Knox (here playing viola d’amore) are joined by violinist Michael Jinsoo Lim in five works by Watras, two by Arad, one by Knox and a duo by American composer Richard Karpen.

Melia Watras: 26 (Sono Luminus SLE-70007) is a fascinating CD inspired by the concept of violists performing and sharing their own compositions. Violists Watras, Atar Arad and Garth Knox (here playing viola d’amore) are joined by violinist Michael Jinsoo Lim in five works by Watras, two by Arad, one by Knox and a duo by American composer Richard Karpen.

All the players have extensive chamber music experience, Arad with the Cleveland Quartet, Knox with the Arditti Quartet and Watras and Lim as co-founders of the Corigliano Quartet. The playing is of the highest standard throughout.

All of the nine works – there are three duos for two violas and two for violin and viola, three solo viola works and a solo violin piece – are world premiere recordings, and each one is a real gem. It’s a terrific CD, and one which should appeal to a much wider audience than just lovers of the viola.

The CD title, incidentally, represents the combined number of strings on the four instruments used.

SPHERES – Music of Robert Paterson is the new CD from the Claremont Trio – violinist Emily Bruskin, cellist Julia Bruskin and pianist Andrea Lam (American Modern Recordings AMR 1046).

SPHERES – Music of Robert Paterson is the new CD from the Claremont Trio – violinist Emily Bruskin, cellist Julia Bruskin and pianist Andrea Lam (American Modern Recordings AMR 1046).

The two major works by this American composer are quite different but form a pair, the shorter and sweeter 2015 Moon Trio, commissioned by the Claremont Trio, being a sister piece for the much longer and more strident Sun Trio, a 1995 work revised in 2008; Donna Kwong, who was a founding member and pianist of the Trio for 12 years from its foundation at the Juilliard School in 1999, is the pianist in the latter work.

The Toronto-born cellist Karen Ouzounian joins Andrea Lam and Julia Bruskin in the Elegy for Two Cellos and Piano, a 2006 work originally written for two bassoons in memory of a well-known New York cellist, and transcribed for two cellos in 2007-08. Quoting liberally from the Bach cello works, it’s a simply lovely piece.

And finally, Henning Kraggerud is the brilliant soloist leading the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra on MOZART Violin Concertos Nos.3, 4 and 5 and the Adagio in E, K.261, a Naxos Music in Motion DVD (2.110368).

And finally, Henning Kraggerud is the brilliant soloist leading the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra on MOZART Violin Concertos Nos.3, 4 and 5 and the Adagio in E, K.261, a Naxos Music in Motion DVD (2.110368).

Filmed before a small audience in the intimate but resonant Akershus Castle Church in Oslo in January 2015, the camera work is understandably a bit limited, with cameras in front on the left, right and centre providing close-ups and occasional tracking. The picture quality could perhaps be a little sharper, but colour and sound are fine.

It’s the playing we’re here for, though, and it’s simply sublime. Kraggerud’s 1744 Guarneri Del Gesù has surely never sounded warmer or brighter, and the joy, exuberance and perfect communication between soloist and orchestral players is a delight to see. The performances throughout are superb, with brilliant outer movements and beautifully judged slow movements.

Kraggerud, who provides his own cadenzas, gives introductions to each work (in Norwegian with English subtitles) with fascinating insight and stories, including what may well be the historical source of all viola jokes; and there is a brief Behind the Scenes bonus track showing preparations for the concert.

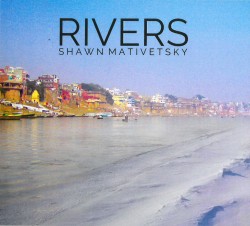

Rivers

Rivers