Old King Cole

Well, the TD Toronto Jazz Festival has come and gone for another year and musicians have had a chance to “strut their stuff” and demonstrate their onstage personas. But one of this year’s daytime features was a series of interviews with some of the featured performers held on the main outdoor stage under the aegis of the Ken Page Memorial Trust.

Well, the TD Toronto Jazz Festival has come and gone for another year and musicians have had a chance to “strut their stuff” and demonstrate their onstage personas. But one of this year’s daytime features was a series of interviews with some of the featured performers held on the main outdoor stage under the aegis of the Ken Page Memorial Trust.

This column is being written before the fact, but I hope these were well attended because they were an opportunity to learn some things about what makes the musicians tick, something about individual philosophies, likes and dislikes, and get a glimpse into, as the series’ title suggests, The Inside Track.

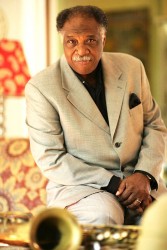

I shared the hosting of the series with artistic director Josh Grossman and one of my interviews was with veteran tenor player Houston Person.

Less known to the younger generation than say, Joshua Redman,Houstonbrings a wealth of experience to his music and the same sort of approach as big-toned tenor players like Gene Ammons, Arnett Cobb and Buddy Tate. He has carved a special niche for himself with his distinctive sassy sound and his expressive style. But to hear him put into words the same sort of things he says through his playing is an entertaining education.

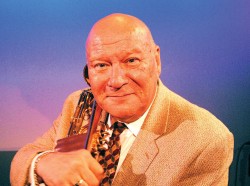

I mentioned Arnett Cobb and Buddy Tate as being two of the great big-toned tenor players. They were also visitors to Toronto and both played at Bourbon Street, the Queen St. club, and one of four clubs operated by Doug Cole, who passed away in June at the age of 87.

Doug was an ex-policeman whose love of jazz was one of the best things that ever happened for the jazz community in Toronto. His first foray into the world of the jazz impresario was in 1956 when he opened George’s Spaghetti House in downtown Toronto. Why George’s Spaghetti House? Simple. That was the name of the business operating there before Doug took it over and he didn’t have enough ready cash to change the sign! It wasn’t an immediate roaring success but Doug kept the faith and eventually it paid off and George’s became a showplace for a Who’s Who of Toronto talent and, on occasion, a visiting out-of-towner. On weekends the music ran an hour later than other clubs in town so musicians could catch the last set on a Friday or Saturday. Regulars would phone in their orders, and their drinks would be waiting for them when they arrived at the club.

Doug opened another room, Castle George, on the floor above, with a house trio, then in 1971 he opened Bourbon Street which presented a steady flow of American artists usually fronting a local rhythm section.

The booking policy at Bourbon Street helped, I believe, to create an awareness of just how good were many of our own Toronto players. A second floor club called Basin Street also showcased jazz on a less regular basis and it is no understatement to say that Doug Cole’s love of jazz helped greatly to maintain Toronto as a leading jazz city after the demise of the Colonial and Town Taverns.

We could certainly use another Doug Cole today.

There may not be a lot going on jazz-wise in Toronto but August is a busy month for out of town festivals.

August 16 to 19 are the dates of the 14th annual Markham Jazz Festival.

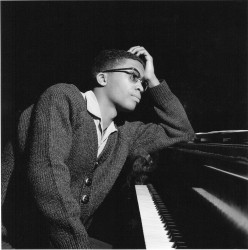

Among the featured musicians are pianist Bill Charlap and vocalist Gretchen Parlato, Tara Davidson, Samba Squad, Three Metre Day with Hugh Marsh, Michelle Willis and Don Rooke, Jeff Coffin and The Mu’tet, and Kellylee Evans.

Entering its 18th year is the Oakville Jazz Festival, August 10 to 12, and the program will include Peter Appleyard, Joey DeFrancesco, Holly Cole and Tierney Sutton.

August 15 to 19 are the dates for the Prince Edward County Jazz Festival with Emilie-Claire Barlow, the Louis Hayes “Cannonball” Legacy Band, Tribute to George Shearing with Don Thompson, Reg Schwager, Neil Swainson, Bernie Senensky and Terry Clarke, and a Boss Brass Reunion concert.

I’ll close out with one of my favourite anecdotes from George’s.The story isn’t really meant as a reflection on the chef. He may not have been an escoffier, who would have been out of place anyway in an Italian restaurant, but generally speaking the food wasn’t bad and sometimes it did hit the spot, as the saying goes. But culinary mishaps can happen and this story does revolve around a steak dinner.

I was playing the club one week and two friends, Alastair and Vivien Lawrie, came in. Alastair’s name will be familiar to those of you who remember his jazz reviews in the Globe and Mail. Anyway, Viv ordered a steak. Now, granted the knives and forks weren’t exactly sterling silver, but her fork actually bent on the steak. So, Alastair called the waiter over and politely explained what had happened. The waiter apologized profusely, left the table and came back with another fork!

And no, we did not play All That Meat And No Potatoes.

This being a two-month issue, I’ll wish you an august summer and see you in September.

Happy Listening!

Jim Galloway is a saxophonist, band leader and former artistic director of Toronto Downtown Jazz. He can be contacted at jazznotes@thewholenote.com.