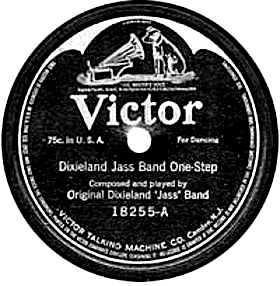

On March 7 1917, two sides “The Dixie Jass Band One Step,” and “Livery Stable Blues” by Nick LaRocca’s Original Dixieland Jass Band were released. It was the first jazz recording issued for sale in the U.S. That honour might well have gone to a group called The Original Creole Orchestra, the first New Orleans Jazz band to tour outside of the South, but in 1915 trumpeter Freddie Keppard turned down an offer from the Victor Talking Machine Company. The story goes that he didn’t want other musicians to be able to steal his music by listening to records.

On March 7 1917, two sides “The Dixie Jass Band One Step,” and “Livery Stable Blues” by Nick LaRocca’s Original Dixieland Jass Band were released. It was the first jazz recording issued for sale in the U.S. That honour might well have gone to a group called The Original Creole Orchestra, the first New Orleans Jazz band to tour outside of the South, but in 1915 trumpeter Freddie Keppard turned down an offer from the Victor Talking Machine Company. The story goes that he didn’t want other musicians to be able to steal his music by listening to records.

Another version claims that the Victor Company wanted the band to make a test recording without pay. Yet another story is that Keppard was offered $25.00 to make a recording – much less than he was making on the vaudeville circuit at that time, although pretty well the going rate for a recording. He refused saying, “I drink that much in gin every day!”

But what was the earliest Canadian jazz recording?

Well, there isn’t much information available about the early Canadian bands or, for that matter, musicians. But in the mid 20s a piano player called Gilbert Watson formed a band which included an American trumpet player called Curtis Little. In 1925 they recorded a couple of numbers in Montreal for Starr Records, probably the first records by a Canadian band.

In these days when a little piece of electronic wizardry no bigger than a square of chocolate can store upwards of 2,000 tunes as MP3s, it is fascinating to look back in time to the early days of phonograph recordings. Before discs, recordings were made on cylinders, a process invented by Edison in 1877. By the early 1900s cylinders were selling by the millions. Then the gramophone disc took over the market. It also had been around since the late 1800s, invented by a German-born American called Emile Berliner. He founded the Berliner Gramophone Company in 1895, and in 1899 the Berliner Gramophone Company of Canada in Montreal. The original discs were only five inches in diameter and intended for toy phonographs.( He also created Deutsche Grammophon in 1898.)

I remember “Wild” Bill Davison, one of the hottest jazz cornet players in the history of the music (and who was already playing in the 1920s telling me about his memories of the early days of discs when it was an acoustic process, before the days of electric recording.

A large metal horn protruded from one wall in the studio. On the other side of the wall was the recording equipment consisting of a needle, connected to the narrow end of the horn, which vibrated to the music and cut grooves in the form of wavy lines into a revolving slab of wax thus creating the sound track. It was, in fact, direct to disc recording. (An interesting aside: in 1977 Rob McConnell and the Boss Brass recorded a limited edition 2-LP set, direct to disc, but they didn’t use wax slabs!).

“Wild” Bill then went on to explain that if the band had to stop for whatever reason during the take, a ring of gas burners would be lowered to the wax in order to melt the surface making it smooth again. You could have a maximum of three attempts before the wax had to be replaced. An added complication was that the band could not set up as it normally would on stage because the louder the instrument, the farther it had to be from the horn in the wall!

A typical example of the difficulties that had to be overcome was described by American writer Rudi Blesh, writing about a recording session with the King Oliver band in the early 20s. The band had two cornet players, Oliver and the young Louis Armstrong and when the band set up around the horn in the wall, Oliver and Armstrong drowned out the rest of the band and had to back off while clarinet player Johnny Dodds had to play right into the horn. Drummer Baby Dodds couldn’t use his bass drum at all, and had to limit himself to a greatly reduced kit.

But that wasn’t the end of it; on the next try they could hear Louis Armstrong, but not King Oliver, so Louis had to move back even more before they could achieve some semblance of balance! Far from ideal conditions you might say.

But let’s go back to that first recording by The Original Dixieland Jass Band. Note that they used the word jass. The transformation of the word jass to jazz is shrouded in conjecture and legend. There is correspondence dated April 19, 1917 from Victor addressed to the Original Dixieland Jazz Band and certainly by 1918 the ODJB was using jazz in the band’s name. One of many stories about the change from jass to jazz is that mischief makers would obliterate the letter ‘j’ from posters advertising the music! But there is no real proof as to who first used the word.

On Friday December 10, 2010 a tongue-in cheek letter from the New York copylaw firm of Lloyd J. Jassin was issued. Here is a partial transcript of the letter. “In a ceremony on Friday, which exuded warmth and openness, the the Jazz world and Jassins came together and reconciled a 95-year dispute over the derivation of the term Jazz.” If you would like to read the very witty transcript you can find it in my expanded column on the WholeNote web site.

The letter closes with this quotation from Martin Luther King: “Everyone has the blues. Everyone longs for meaning. Everybody needs to love and be loved. Everybody needs to clap hands and be happy. Everybody longs for Faith. In music, especially that broad category called Jazz, there is a stepping stone towards all of these.”

A sad note. Last month we lost George Shearing and I miss his sense of humour almost as much as his music. One of my favourite examples was the following; “When people ask me how is it I was a musician, I facetiously say that I’m a firm believer in reincarnation and in a previous life I was Johann Sebastian Bach’s guide dog.”

Happy listening.

Jim Galloway is a saxophonist, band leader and former artistic director of Toronto Downtown Jazz. He can be contacted at jazznotes@thewholenote.com.