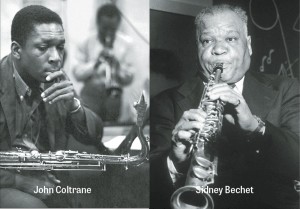

A survey in the 60s claimed that the average lifespan of jazz musicians was 44 and certainly there are facts to support this. Leon Bismark “Bix” Beiderbecke only made it to 28; Clifford Brown died at the age of 25 in a car accident; Guitarist Charlie Christian died of tuberculosis at age 25; John Coltrane had liver cancer and died at age 40. Albert Ayler drowned at age 34; Guitarist Lenny Breau died a violent death at age 43. Another violent death was that of Lee Morgan, shot by his common-law wife at age 33. Jaki Byard, a pianist, saxophonist and teacher who recorded with some of jazz’s most important figures, was shot dead February 11 in his house in Queens. (Mind you, he was 76 by then!)

A survey in the 60s claimed that the average lifespan of jazz musicians was 44 and certainly there are facts to support this. Leon Bismark “Bix” Beiderbecke only made it to 28; Clifford Brown died at the age of 25 in a car accident; Guitarist Charlie Christian died of tuberculosis at age 25; John Coltrane had liver cancer and died at age 40. Albert Ayler drowned at age 34; Guitarist Lenny Breau died a violent death at age 43. Another violent death was that of Lee Morgan, shot by his common-law wife at age 33. Jaki Byard, a pianist, saxophonist and teacher who recorded with some of jazz’s most important figures, was shot dead February 11 in his house in Queens. (Mind you, he was 76 by then!)

On a slightly less morbid note Sidney Bechet, born in New Orleans in 1897 moved permanently to France in 1950 and had an international hit with “Petite Fleur” at the age of 53, becoming something of a national hero in his adopted country.

Some years ago I was playing at La Huchette in Paris and on the way back to my hotel one night what did I hear coming from a late-night bar? Bechet’s version of “Petite Fleur,” more than 20 years after his death in Paris (from lung cancer on May 14, 1959 on his 62nd birthday). Sigh.

Continuing the litany: Leon “Chu” Berry, hardly even remembered today, was a big, fat-toned tenor player, killed in a car accident at 33. And some of you might remember guitarist Emily Remler from her appearances here. She died of a heart attack at 32. Jimmy Blanton, pioneering bass player died of tuberculosis at 23, Frank Teschemacher whose reed playing influenced many of his successors was killed in a car crash. He was only 25. And these are only a few of the many fine musicians who left us too soon.

The flip side? If the lifestyle doesn’t kill you, the joy of the music will keep you going to a ripe old age!

One more for the road: In the days of prohibition in the U.S. there was plenty of “bathtub gin around but good alcohol was hard to find.” I remember Wild Bill Davison telling me that they always liked playing Detroit because there was a late-night bar where you could get good whisky which was hauled from Canada on a skiff under the surface of the Detroit River. Sometimes the delivery was a bit late, but it was worth the wait! And quite often the labels were washed off, not that it mattered too much, because the booze was good.

But don’t get the idea that prohibition didn’t ever exist in Canada. It was present in various stages, from 19th-century local municipal bans to provincial bans in the early 20th century, and national prohibition from 1918 to 1920. Alcohol was illegal in Prince Edward Island until 1948. Parts of west Toronto did not permit liquor sales until 2000. But by and large the enforcement of prohibition laws is a little bit like King Canute trying to turn back the tide, and, in its various forms, it has spawned drinking songs throughout the centuries: “Whiskey in the Jar,” “Little Ole Wine Drinker Me,” “ One for My Baby (and One More for the Road),” “What’s The Use of Getting Sober (When You’re Gonna Get Drunk Again),” “The beer I had for breakfast wasn’t bad, so I had one more for dessert (Sunday Morning Coming Down),” and “Gimme That Wine,” to name only a few.

Meanwhile, getting back to the business of longevity, the mean life span for a survey of 33 male symphony conductors was 75.6 years.

Moral? Spend a lot of time waving your arms about.

I wish you all happy listening – and try to make some of it live.

Jim Galloway is a saxophonist, band leader and former artistic director of Toronto Downtown Jazz. He can be contacted at jazznotes@thewholenote.com.