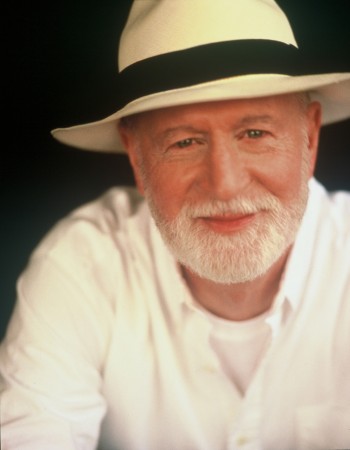

During a very brief period of palliative care and shortly after celebrating his 95th birthday, Jack passed away this past January, at Markham Stouffville Hospital. His Bandstand column occupied this very spot in The WholeNote, right before the listings, for more than 14 years, and readers who regularly made their way here to find him, will feel the loss, as will I. Two days before his passing he asked me to make sure to tell WholeNote colleagues and you, his readers, how much you meant to him.

During a very brief period of palliative care and shortly after celebrating his 95th birthday, Jack passed away this past January, at Markham Stouffville Hospital. His Bandstand column occupied this very spot in The WholeNote, right before the listings, for more than 14 years, and readers who regularly made their way here to find him, will feel the loss, as will I. Two days before his passing he asked me to make sure to tell WholeNote colleagues and you, his readers, how much you meant to him.

Right up until COVID-19 restrictions put paid to live community music making, Jack was still playing regularly (tuba, trombone and bass trombone) as a 25+ year member in The Newmarket Citizen’s Band, Resa’s Pieces Concert Band and Swing Machine, a Toronto based big band. “Not bad for someone with COPD” he once told me, regaling me with a tale of how his doctor had said it was impossible, so he should keep it up.

Similarly, he stuck to his WholeNote duties to the last. His final completed column for The WholeNote (December/January) was an uncharacteristically “deep dive” into reminiscing about his early years in Windsor. To the last, we were chatting almost daily about the column that would have been in this spot, on the subject of circus bands. He shared with me each nugget of information he had gleaned from sources as divergent as his own unruly archives and “Mr. Google.”

His wife of 35 years, Joan Andrews, told me last week that the plan is to have “a celebration of his life at a future date, when it is possible to gather together and create live music once again.” And what a life it was.

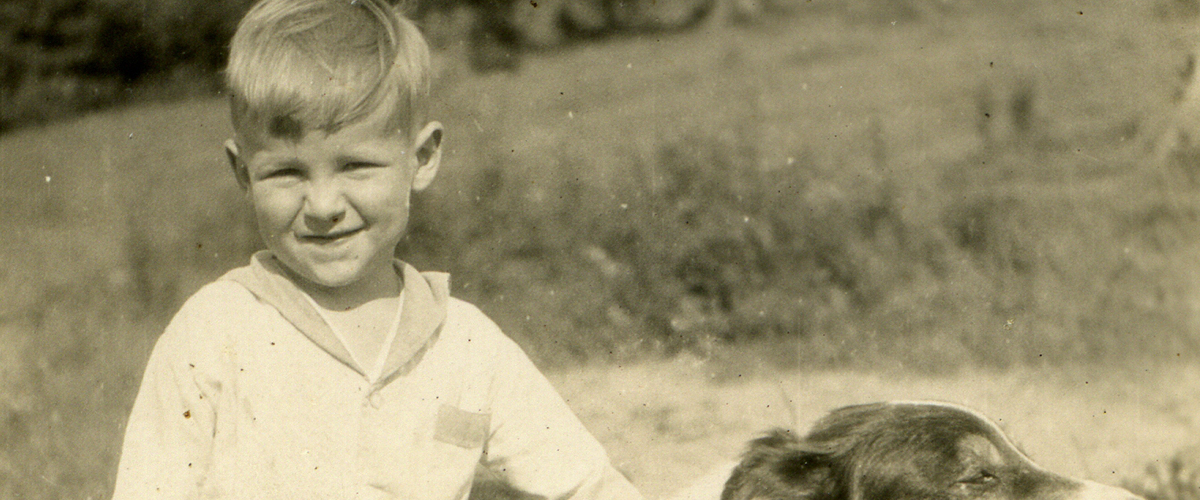

In a 2014 interview in The WholeNote, MJBuell asked Jack if there had always been music in his home: “Always” was the reply. “Lots of radio music from Detroit stations. My parents met in a Gilbert and Sullivan production. It was in the auditorium of the place I eventually went to high school. My mother, Nan, was a semi-professional singer, church soloist, and for a time, a member of the Detroit Light Opera Company. My father, Archie, was a dedicated opera fan, and the Metropolitan Opera was on our radio every Saturday afternoon. My mother organized a vocal quartet which practiced regularly in our living room for some years. Probably my earliest musical memory would be my mother singing the role of Buttercup from HMS Pinafore as she worked around the house.”

In a 2014 interview in The WholeNote, MJBuell asked Jack if there had always been music in his home: “Always” was the reply. “Lots of radio music from Detroit stations. My parents met in a Gilbert and Sullivan production. It was in the auditorium of the place I eventually went to high school. My mother, Nan, was a semi-professional singer, church soloist, and for a time, a member of the Detroit Light Opera Company. My father, Archie, was a dedicated opera fan, and the Metropolitan Opera was on our radio every Saturday afternoon. My mother organized a vocal quartet which practiced regularly in our living room for some years. Probably my earliest musical memory would be my mother singing the role of Buttercup from HMS Pinafore as she worked around the house.”

Jack was bitten by the band bug in grade 11 when he joined The High Twelve Club Boys Band (sponsored by a service club), and then the local Kiwanis Boys Band. The Boys Band was “borrowed” by the commanding officer of the local naval training unit who’d been asked to recruit a reserve band. Boys as young as 12 through 17, whose parents gave permission, found themselves Probationary Boy Bandsman with a uniform and rehearsal pay – for Navy parades, concerts in the park and Navy events.

It was the start of a lifelong Navy association, going on active service after high school; as he wryly described it in the April 2014 interview article, “learning some new instruments – radio and radar.” When WWII ended he completed his undergraduate degree at U of T where he played in the Varsity Band, the Conservatory Concert Band and the U of T Symphony. One memorable university summer, he recalled in that interview, he played trombone six nights a week in a dance band at the popular Erie Beach Pavilion – six days a week, from nine until midnight. And then Sundays they’d go to Detroit and hear all the touring big bands – Ellington, Kenton, Burnett, Herman, Dorsey.

Jack MacQuarrie returned to sea during the Korean War as a Navy Lieutenant Commander and diving officer, laying aside music during those seven years, but never since. With music fuelling his lungs, mind and spirit, he returned to university, acquired an MBA and then did four years of graduate studies in engineering – investigating human performance in hostile (underwater) environments. He received a Massey Fellowship under Robertson Davies. He worked for some time at marketing in the airborne electronics business. He was a past president of the Skywide Amateur Radio Club, was the first instructor for the Hart House Underwater Club and to the last remained active in the Naval Club of Toronto. In January 2013 MacQuarrie was awarded the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal for contributions to Canada.

Jack MacQuarrie returned to sea during the Korean War as a Navy Lieutenant Commander and diving officer, laying aside music during those seven years, but never since. With music fuelling his lungs, mind and spirit, he returned to university, acquired an MBA and then did four years of graduate studies in engineering – investigating human performance in hostile (underwater) environments. He received a Massey Fellowship under Robertson Davies. He worked for some time at marketing in the airborne electronics business. He was a past president of the Skywide Amateur Radio Club, was the first instructor for the Hart House Underwater Club and to the last remained active in the Naval Club of Toronto. In January 2013 MacQuarrie was awarded the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal for contributions to Canada.

In one episode he wrote about in The WholeNote, in 2014, he and Joan Andrews enrolled as volunteers in research on brain function and aging, comparing musicians with non-musicians, at the Baycrest Centre. It was one memorable story among hundreds over the years as he regaled readers with great anecdotes and dreadful puns – above all else spreading the word about all the people he was in touch with who were keeping community band music making alive. Readers so inclined can find his most recent column on our website and then scroll back in time, column after column, as I’ve been doing this last while.

Curious as to what might have changed or not over the course of this pandemic year, I went to look at the February 2020 column (wondering for a moment if just reprinting it would serve here to give readers a taste of the man). It didn’t disappoint: from Groundhog Day to the Newmarket Citizens Band’s bright idea of building their Christmas party around an open rehearsal: “How often do tuba players chat with clarinet players, after all?”; and from Henry “Dr. Hank” Meredith’s collection of 300 bugles, to Jack’s latest musings (something he was passionate about) on what bands should and shouldn’t take into consideration when selecting repertoire.

There’s one more snippet from that column that is a fitting place to end this – an exchange with a reader: “He [the reader, Bernie Lynch] recounted a bit about his personal band involvement, from Orono around 1946, to Weston in 1950, and Chinguacousy in 2012. ‘Never a very good performer but always a good participant,’ is how he describes himself. [Well] we need more good participants. Let us hear from more of you out in the community music world!”

A fitting place to end except for one thing. Jack always tried to throw in something at the end – a quip, a “daffy definition,” a pun – that would get a smile.

So here’s mine: the part of his February 2020 column that he got the biggest charge out of researching and writing, was of all things, a piece of music called “The Impeachment Polka”. Jack would have liked that.

David Perlman, with files from MJ Buell

With the COVID-19 pandemic having passed the one-year mark – and with recent ominous developments indicating we’re likely looking at another year of it – and with the university teaching year just finishing, this article will be a kind of retrospective diary of the past annus horribilis from the perspective of a jazz musician and teacher.

With the COVID-19 pandemic having passed the one-year mark – and with recent ominous developments indicating we’re likely looking at another year of it – and with the university teaching year just finishing, this article will be a kind of retrospective diary of the past annus horribilis from the perspective of a jazz musician and teacher.