Many would agree that 2020 was the worst we’ve ever been through and we were all anxious to see the end of “The Year of Living Covidously.” So good riddance, 2020, and don’t let the door hit your ass on the way out. But of course the root of all our problems and suffering – the pandemic – hasn’t gone anywhere and simply flipping over to January of a new year on the calendar hasn’t solved it, any more than anything else we’ve tried. And Lord knows we’ve tried lots, at least most of us. Masking up, staying at home, social distancing, keeping our bubbles small, working from home (that’s if you still have a job), forgetting what eating in a restaurant or hearing live music feel like. Stores and schools closed, then open, then sort of half-open, then not. And still the numbers go up as we chase this invisible enemy, to the point where The Myth of Sisyphus no longer seems a metaphor but something we’re living on a daily basis. Keep pushing that boulder.

None of this is to say that we should join the ranks of the anti-mask loonies or herd-immunity-at-any-cost-COVID-deniers, not at all. We have only to look south of the border to see how well that hasn’t worked, as Samuel Goldwyn might have put it. Clearly we must stay the course with these mitigation measures because they’re the best tools we have and, just as clearly, we would be even worse off without abiding them in the last year. It’s just that after nine months and counting of cave-dwelling isolation… well, it’s getting harder. To quote one of Mose Allison’s more sardonic later songs – “I am not discouraged. I am not down-hearted. I am not disillusioned… But I’m gettin’ there… yeah, I’m gettin’ there.”

And You Thought Jazz was Confusing

As someone who has spent an awful lot of time over the past 30 years being out of the house maintaining an insanely gruelling work regimen – full-time days at a law library, a busy playing schedule, with writing and teaching thrown in more recently – I haven’t found this much staying at home all that hard. I suspect I speak for many when I say that what I have found hard is the disorienting brain-fog which has resulted from so many months of anxious uncertainty about how we’re supposed to find a way out of this mess and how long that will take. Part of it has to do with the nature of the virus itself and how it behaves, which is proving elusive even to epidemiologists.

I believe in following the science and am inclined to cut our leaders, both political and medical, some slack because none of this came with a road map, but often a lack of consistent messaging and transparency from them have made things worse. Sometimes it seems like they’re making it up as they go along. Then there’s the mounting socio-economic and psychological fallout from all of this, hence the Twilight Zone fog we’re stumbling around in, as if somebody opened up a great big can of WEIRD. The horrific and (almost) shocking events of January 6 only served to ratchet up the insanity of everything a few notches. A couple of days later while swimming upstream in this mucky soup, I began laughing out loud while drooling slightly as a strange thought hit me: compared to all of this, jazz seems normal, a veritable oasis of reason, order and sanity. How often do you hear that?

Throughout its history, except for a couple of decades in and around the 30s through the 40s when it was popular music, jazz has suffered from a reputation of being confusing, flighty, inaccessible, too complex and abstract to be really enjoyable. Its practitioners were seen as low-life bohemians, drunks and drug addicts who wore strange clothes and affected insider hipster dialogue. Like weirdsville – dig, baby. And all this was before jazz discovered atonality. Like the coronavirus itself, jazz cannot be seen or touched. Really it can only be heard and felt, but at least it won’t make you sick or kill you – at least not most of the time. But it’s only taken life during a little old pandemic to make jazz seem solid, almost intelligible.

For example, a couple of days ago I was practising the bass – for what, I couldn’t tell you – when I began playing a blues in F. And sure enough, just like always, the structure was 12 bars long and no matter how many different chord-change variations I played, it always went to a B-flat 7 in bar five. And the particular minor-major dichotomy of that chord change had the same thrilling and mysterious rub as ever. It’s nice to know you can count on something these days.

It’s the same with jazz records. For the umpteenth time the other day I listened to “Shoe Shine Boy” from the immortal 1936 Jones-Smith Incorporated session which marked Lester Young’s recording debut. And it knocked me out just as much as always – the darting velocity and swing of it, Young’s swooping two-chorus masterpiece solo as brilliant and daringly inventive as ever. Ineffable, yet carved in stone.

It’s the same with jazz records. For the umpteenth time the other day I listened to “Shoe Shine Boy” from the immortal 1936 Jones-Smith Incorporated session which marked Lester Young’s recording debut. And it knocked me out just as much as always – the darting velocity and swing of it, Young’s swooping two-chorus masterpiece solo as brilliant and daringly inventive as ever. Ineffable, yet carved in stone.

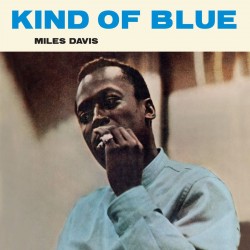

Then over to Kind of Blue, and sure enough, Jimmy Cobb’s cosmic ride-cymbal splash just ahead of Miles Davis’ solo entry on “So What” – still for me the most magic moment of many on that magical record – was still there in all its glory. It’s not that I expected these and other gleaming gems to have changed – after all, once music is recorded, it’s fixed in place forever and I know that. But these days, you find yourself wondering.

Then over to Kind of Blue, and sure enough, Jimmy Cobb’s cosmic ride-cymbal splash just ahead of Miles Davis’ solo entry on “So What” – still for me the most magic moment of many on that magical record – was still there in all its glory. It’s not that I expected these and other gleaming gems to have changed – after all, once music is recorded, it’s fixed in place forever and I know that. But these days, you find yourself wondering.

Jazz is neither weird nor confusing. Like everything else, it only seems so if you don’t understand it, or at least try. But life with COVID is decidedly weird and confusing. The only saving grace is that like wars, pandemics eventually end, whereas jazz is forever. Thank goodness.

Sound the Knell Again

As I mentioned in a previous column, 2020 was a horrible year for jazz musicians dying and unfortunately this parade has continued through early January. New York pianist Frank Kimbrough died of a sudden heart attack on December 31 at the age of 64. A very creative improviser/composer and a revered teacher, Kimbrough was known for his long association with the Maria Schneider Orchestra, for founding the Herbie Nichols Project with bassist Ben Allison, a longtime collaborator, and for being a charter member of the Jazz Composers’ Collective. His last recording was the ambitious 6-CD 2018 release, Monk’s Dreams: The Complete Compositions of Thelonious Sphere Monk, with multi-reedman Scott Robinson, bassist Rufus Reid and drummer Billy Drummond. Kimbrough died far too young and his death will leave a big hole.

Composer/arranger Sammy Nestico, best-known for his prolific writing for Count Basie, died on January 17 at 96. At least he made it to a ripe old age and if I had a dollar for every time I played one of his charts when I was coming up, I’d be a rich man today.

Composer/arranger Sammy Nestico, best-known for his prolific writing for Count Basie, died on January 17 at 96. At least he made it to a ripe old age and if I had a dollar for every time I played one of his charts when I was coming up, I’d be a rich man today.

And on the very same day, the wonderful pianist Junior Mance died at 92. Junior had been suffering from dementia in recent years and his loss will be felt keenly by Toronto jazz fans, as he was a frequent visitor to jazz clubs here over many years. He came out of Chicago during the early bebop years playing with the likes of Sonny Stitt and Gene Ammons before settling in New York for a long career. He met the Adderley brothers while serving in the army and played in their first mid-50s quintet. He led a trio for many years, releasing a string of fine records. His playing was a unique blend of earthy blues and bebop wed with elegance and a gentle touch. He was also prized as an incisive, swinging accompanist for singers and in small groups such as the Johnny Griffin-“Lockjaw” Davis Quintet, and with Dizzy Gillespie. He was a regular at Toronto clubs such as the Café des Copains and the Montreal Bistro. I feel his death personally as I had the pleasure of first playing with Junior for two weeks in 1979 at Bourbon Street in a trio backing singer Helen Humes. I was pretty young and green at the time but Junior made the gig easy and fun with his energetic, straight-ahead style and we remained friends ever after. Above all, he was a wonderful person – soulful, warm, cheerful and friendly with a smile that lit up the room. He’ll be greatly missed.

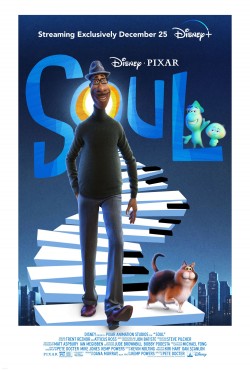

Soul

As an antidote to the generally gloomy tone of this article – sorry – I highly recommend watching the 2020 Disney/Pixar animated film, Soul. It captivated me immediately and lifted my spirits throughout with its imaginative originality, humour and wit. Right off the bat it had me laughing as I saw the usual Disney castle image off in the distance, but “When You Wish Upon A Star” was played in a satirical, messy brass style that sounded just like a bad high-school band and I realized this was not going to be the usual glossy or sugary Disney fare. Although an animated film, it’s really intended for adults, though kids would certainly enjoy it. The story concerns Joe Gardner, a talented and dedicated jazz pianist who has never quite made it, and who finds himself teaching middle school music. Just as, against his better judgment, he accepts a full-time position, he catches a big break when an ex-student drummer arranges for him to audition with a top-flight alto saxophone star. Joe plays out of his skin and lands the gig which opens that night, only to fall down an open manhole cover on the way home, plummeting to his apparent death. And that’s all in the first 20 minutes. I don’t want to play spoiler any further, but suffice it to say that the rest of the story is a thoughtful and complex rollercoaster ride worth seeing more than once. Although not entirely about jazz, the jazz content is rich and believable on various levels and doesn’t have any of the stumbles that many movies purporting to be about jazz often suffer from. All of the key elements – the story, the music (jazz and otherwise), the voice-over acting (Jamie Foxx and Tina Fey are the principals) and above all the animation – are brilliant. It’s a visually stunning movie with the power to do something rare these days – to truly delight us and make us forget, at least for a couple of hours, the awful mess we’re in. I’ll take it.

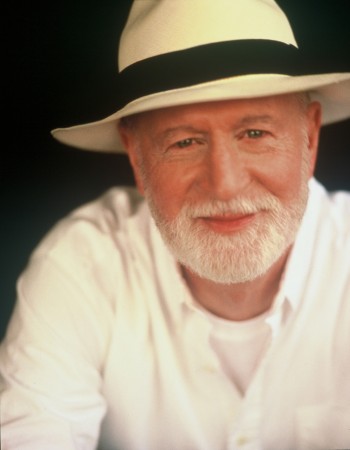

Toronto bassist Steve Wallace writes a blog called “Steve Wallace jazz, baseball, life and other ephemera” which can be accessed at wallacebass.com. Aside from the topics mentioned, he sometimes writes about movies and food.