What is 12-ET A440 anyway?

Over the course of more than a decade, my WholeNote editor and I have developed a certain ritual around each upcoming article. After we agree on the story that month, it’s usually followed by a conversation on the phone, where I present my take, ask practical questions, and fret about approach and tone. My editor offers editorial guidance, and invariably offers an offhand quip or two in regard to whatever I am fretting about. As lay rituals go, I find it reassuring.

This month’s conversation point revolved around “a truly fret-worthy concern,” as my editor described it – for Labyrinth Ontario, the subject of this story, and all practitioners of modal music. One of LO’s signature concerns around its core concept of “modal music” is the ever-growing bias for “flattening out” traditional regional tunings, some very ancient, and modal-melodic performance practices in favour of the ubiquitous so-called “concert pitch.” That’s the Western-origin A440 pitch, the “settler” in the tuning house, which, given its ubiquity, we may assume has been around for centuries. But no: it was reconfirmed under the name ISO 16 recently as 1975 by the International Organization for Standardization.

Concomitant with it is the older model of 12-tone equal temperament (12-ET), where the octave is theoretically divided into 12 equal intervals. Taken together, this conglomerate-tuning model, with minor deviations, defines the sound of the modern symphony orchestra, its many spinoffs, and nearly all of the world’s commercial vernacular music.

Incrementally throughout the course of the last century, starting in Europe and assisted by mass media, 12-ET A440 has spread globally to become the international tuning standard for music-making even in remote corners. It’s the ubiquitous factory preset tuning found on every electronic keyboard I know of. It has influenced the way most people hear music, how they play acoustic instruments and how they sing. In more recent decades it’s become the default tuning for numerous music genres around the world, colonizing something that resonated with indigenous character before 12-ET A-440’s hegemony took hold.

Am I exaggerating for effect here? Yes, a bit. But only a bit.

Granted, an international tuning standard such as 12-ET A440 may make it easier for musicians from many geographically and culturally distant – even continentally disjunct – regions to play together. But there is a hidden-in-plain-hearing trade-off. Accepting 12-ET A440 wholesale poses an existential challenge to some regionally distinct tuning systems and thus to the melodic practices that engendered them – practices that are embedded deep within their musicians’ fingers, voices and hearts, and within the hearts of their audiences.

In this way, when applied across the board, 12-ET A440 can ultimately prove to be an (often covert) challenge to the cultural identity of a community. Often it’s these very regionally specific musics, sonic terroir if you will, which allow musicians to tell their most resonant stories – sometimes thereby inadvertently touching the most universal in us because of their singularity. Such regional music is the poetry of the human condition where you live.

Back to Labyrinth Ontario

I first introduced LO in my September 2017 WholeNote column, where I described the then-fledgling organization and its two Toronto-based founders (Persian tar player and teacher Araz Salek, artistic director, and keyboardist, composer and sound designer Jonathan Adjemian, admin director, as “focusing on the education of a new generation of musicians and also audiences,” in its inaugural season of music workshops and concerts. LO had a very specific mission: a commitment to promoting the teaching and appreciation of the varied yet affiliated modal music traditions of large swathes of Asia, North Africa and Mediterranean Europe.

In that inaugural season, the “spirit of an extended modal family” was reflected in LO’s ambitious lineup featuring 11 masters of Greek, Turkish, Bulgarian, Iranian, Azerbaijani, Arabic, Kurdish and Afghani music traditions. In Toronto we saw fruitful musical interactions reflecting the demographic musical reality on the ground in week-long workshops and concert performances.

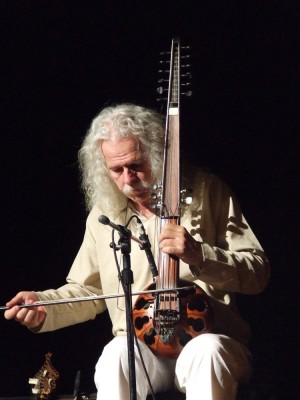

I then dove deeper into LO’s vision in my May 2018 column where I explored its roots in the successful Labyrinth Musical Workshop founded in 2002 on the Greek island of Crete by prominent world musician, composer and educator Ross Daly. One of the pioneers exploring the larger maqam (Arabic modal system) family, Daly stated that “Labyrinth is more than a musical workshop, it is a way of life through music,” an ethos running through his projects. Running ever since, that successful model has inspired affiliated “modal music” workshops in Greece, Turkey, Germany, Spain, Italy, USA and Canada, fostering an expanding international Labyrinth network.

I then dove deeper into LO’s vision in my May 2018 column where I explored its roots in the successful Labyrinth Musical Workshop founded in 2002 on the Greek island of Crete by prominent world musician, composer and educator Ross Daly. One of the pioneers exploring the larger maqam (Arabic modal system) family, Daly stated that “Labyrinth is more than a musical workshop, it is a way of life through music,” an ethos running through his projects. Running ever since, that successful model has inspired affiliated “modal music” workshops in Greece, Turkey, Germany, Spain, Italy, USA and Canada, fostering an expanding international Labyrinth network.

And in that same article, York University ethnomusicologist Rob Simms offered a broader context for understanding LO’s modal music model. He proposed that the network of trade routes known as the Silk Road can provide us with “an incredible continuity of musical expression stretching from North Africa, Southern and Eastern Europe, clear across to Central Asia and Western China. This massively extended musical family shares similar social contexts for performance, aesthetics, philosophy, performance practice, instrumentation and musical structures – rhythmic cycles, forms and melodic modes (scales with particular behaviours or personalities).”

Labyrinth Ontario entering 2021

I called Jonathan Adjemian to find out what Labyrinth Ontario is managing to do today, and we chatted first about its origins, as described here. “It was Araz’s idea,” Adjemian stated. “He’d been to Crete’s Labyrinth headquarters already to teach and perform for quite some time. Inspired by what was going on there we incorporated the company, taking us about nine months to fundraise and organize the first workshops in 2018.”

“What really drew me to LO,” he continued, “ is that it is a way of not just telling the history of the regions we represent, but of showing that history as something that still lives on in music today. And I think always one of the places where you find peoples’ history is in culture: in their music, dance, food and costume; and these are all things that are shared.”

Labyrinth on Crete is working in a single region where these traditions originate, Adjemian observes. “Here in Toronto we are dealing with diasporic conditions with different communities with their own histories and languages. There’s a lot of work to be done in Toronto if the LO model is going to be successful here. First of all we’ve got to find those skilled musicians who have settled here, but who haven’t necessarily had an easy passage into our local music scene. We’ve stepped up to work with newcomers and I think that’s born a lot of good fruit.”

Araz Salek’s linguistic abilities have served as a convenient bridge between Toronto’s disparate music communities, Adjemian adds. “It’s also often not understood here that Iran is a very ethnically diverse country. You can talk about enmities between peoples, but this is also a region where you’ve had people with different languages, customs and religions playing music together for hundreds of years.”

For example, “One of the largest ethnicities in Iran is Azeri, Araz’s background, but he also grew up speaking Farsi, the official language of the country. As a Farsi and Azeri [a Turkic language] speaker, therefore, he can speak with Iranian and Turkish speakers or to people who speak Dari, one of the main languages of Afghanistan,” and thus connect with musicians in sometimes-isolated GTA communities.

That sort of connection extends beyond spoken language to music. A good example is Afghani rabab master , a Dari speaker whom LO recently presented in one of their park videos. “Araz can speak with him and knows some of the customs around social interactions. It’s not that their cultures are exactly the same, but that there is a bridge between them.”

“Araz can also learn music from Nikzad, and this summer he took some rabab lessons,” Adjemian continues.”To be clear, it’s not the music that Araz plays, but the principles that he has to understand to be able to play it, such as the notion of rhythmic cycles, and scales that have quarter tones are familiar enough to be transferrable. And by the way, a ‘quarter tone’ interval in this context still doesn’t mean a fixed pitch – rather it means lots of possibilities for different pitches. And you need a certain kind of ear training to understand all this. Araz has that, given his background.”

LO’s project, Adjemian says, is about “showing that sharply defined areas with lines between them, with different people between those lines, is not how the world actually looks today, looked in the past – or how it worked. You can talk about musical centres, however.”

From there the conversation flows easily to LO’s ongoing development of its 12- to 15-piece Labyrinth Ensemble earmarked for launch next year. “We’re picking a few musical centres and working within them as a way to create a literacy to approach all these musics and musicians” he states. The regional musical centres on the short list include Ottoman, Syrian/Levantine and Iranian/Azeri.

As for LO programming during our current pandemic restrictions, Adjemian offers kudos to the Toronto Arts Council which has funded two years in a row of LO concerts in city parks, emphatically committing to supporting art happening throughout Toronto, not just in the downtown core. “This year due to COVID-19, we have chosen to shoot six video concerts and associated interviews with the musicians in six different parks.”

Three videos are already up on the LO website, ready for free viewing. The first to be uploaded was the Turkish Music Ensemble featuring Begum Boyanci (vocalist), Agah Ecevit (Turkish ney) and Burak (baglama) performing two Turkish songs in a very verdant Monarch Park.

Mentioned earlier, the video by Afghan rabab), accompanied by tabla), presents two Afghani instrumentals, Banafsha by Ostad M. Omar, and Ai Bot bi Rahm at Riverdale Park. The third video, shot at Flemingdon Park, is of the Varashan Ensemble led by the master Pedram Khavarzamini (tombak) with Alinima Madani and Ilia Hoseini also on tombaks.

The other three videos filmed this summer will be released, one a week, into December.

Somali singer and kaban (oud) player Omar Bongo was videoed at Downsview Dells Park. Representing Iranian classical instrumental music, the Araz & Pedram Duo performed at Grey Abbey Park, with Araz Sale (tar) and Pedram Khavarzamini (tombak) doing the honours.

The final group is Ori Shalva: Georgian Choir, live at Banbury Park just off Bridle Path, north of Lawrence. This family group, singing Georgian three-part polyphonic songs, consists of Shalva Makharashvili, Andrea Kuzmich and their sons Shalva-Lucas Makharashvili and Gabo Makharashvili. Ori Shalva continues the age-old practice of Georgian family ensemble singing, preserving its essence halfway around the world from its mountainous homeland at the crossroads of Europe and Asia. I’ve keenly followed these inspirational pioneers of Georgian choral music in Canada ever since their first gig.

With them, and the other five ensembles and soloists presented by LO online, the “flattening out” of these traditional regional musics is not on the table. Judging from this series, it appears the future of Toronto’s modal music-making is in good hands.

Andrew Timar is a Toronto musician and music writer.