World music: a sometimes contentious term that entered the lexicon twice, 25 years and two continents apart.

Too few sources reflect that the term “world music” was first used around 1962 in US academia as an inclusive catchall for performance and lecture courses; they focus, rather, on its re-application as a new marketing tag by UK record producers, label owners and retailers in 1987.

The 1962 US world music ensemble course bug took a few years to infect schools north of the border. But after a rocky initial startup period, it slowly spread across Canada, mostly in the decades bracketing the new millennium. Although it should be said that York University was probably the site where world music ensemble credit courses were first launched in this country by its Music Department founding chair, R. Sterling Beckwith, as early as the 1969/1970 academic year.

Fifty years later, world music courses are no longer the exotic music school outliers they were initially seen to be by many. They have become mainstays at some of the largest Ontario universities and colleges, offering practising professional musicians teaching opportunities, while introducing thousands of students to a wide diversity of approaches to making music – far beyond what classical and jazz programs can offer. I would argue that they prepare students to open their minds via practical experience, potentially allowing them to meet the challenges of cultural diversity in our increasingly multicultural urban and internet spaces.

York U’s Department of Music’s pioneering commitment to global music doesn’t show signs of slowing down, with nine concerts alone in its March World Music Festival and an advertised “20-plus international cultures represented.” It’s followed closely by early April concerts by the University of Waterloo Balinese Gamelan and University of Toronto’s World Music Ensembles.

So, What’s In a Name?

So, What’s In a Name?

Judging from the liberal use of the term “world music” at these three universities, all appears to be well with this 20th-century term and learning approach. Looking deeper however the tag is facing increasingly frequent challenges from voices on all sides: academics, presenters, labels and performers.

So let’s take the pulse of three Ontario university world music ensembles today, and the direction they may be headed, by looking at what they are up to, and talking with some of the instructors.

York University’s World Music Festival, March 14 and 15: report from the front lines

Produced by Prof. Sherry Johnson, York U’s mid-March World Music Festival, according to the Music Department website “…[is a] global sonic tour … of York’s world music program.”

All the concerts are at the Tribute Communities Recital Hall, Accolade East Building, York U.

March 14 at 11am the festival launches with the Cuban Ensemble directed by Rick Lazar and Anthony Michelli. Lazar also directs the Escola de Samba later the same day. West African Drumming: Ghana directed by respected master drummer Kwasi Dunyo, West African Drumming: Mande directed by Anna Melnikoff, and Caribbean Music Ensemble directed by Lindy Burgess, all on March 14. Then on March 15, Charles Hong directs the Korean Drum Ensemble, Sherry Johnson the Celtic Ensemble, and Kim Chow-Morris conducts the Chinese Classical Orchestra. It then wraps, March 15, with an evening concert by the Balkan Music Ensemble directed by Irene Markoff. (Please refer to our listings for exact times for all concerts.)

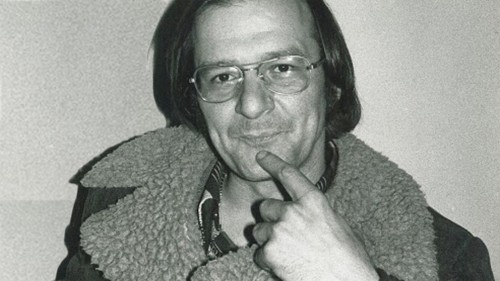

Rick Lazar: Escola de Samba and Cuban Ensemble director

I contacted Lazar about his world music teaching practice. He emailed a very detailed report on his teaching approach and on the music his students are presenting.

Lazar has had extensive experience teaching various ensembles at Humber College (1995 to 2005) and since 2003 at York University. Make no mistake; he’s no ordinary sessional instructor. His knowledge of and passion for world drums makes him a first-call drummer for a diverse array of artists. Voted Percussionist of the Year five times by Jazz Report magazine for his work with many bands and headline singers, his popular Toronto groups Montuno Police and Samba Squad (celebrating its 20th anniversary this year) have both released multiple albums.

At York, “I teach two ensembles: Escola de Samba and Cuban Music, each divided into two classes,” he began. “My classes are mostly made of non-music majors. While most of the class time is devoted to getting these often untrained students to gel into a group, I also provide notes on the history of the music [giving students essential cultural context] – and test them on it too!“The Escola de Samba classes feature hands-on percussion: all the students have to play a standard samba instrument including the surdo (bass drum), caixa (snare drums), agogo (bells), tamborim and ganzas (metal shakers). These classes may have up to 30 participants. [As for genres in our repertoire] this year we’re covering samba, samba reggae, and axé another popular music genre from Bahia, Northeast Brazil.

“[My teaching strategy] is to simplify rhythmic patterns for the lead instruments as none of the students are drummers and can’t play the typical patterns up to speed. For example, while the students won’t be able to master the tamborim carreteiro (“ride” technique) in a single term they can learn idiomatic fanfares and rhythmic patterns.

“For the March 14 concert, one class is doing a samba reggae dance feature [since dance is integral to the genre]. Songs we’ll be doing this year are (samba), Enquanto Gente Batuka in the pagoda genre, , and Embala Eu in samba de roda, an older Afro-Brazilian dance type.”

“In the Cuban Music ensembles I teach a section of first and second year undergrads plus a section of senior-level students. Both perform Cuban folkloric music with drums, dance and songs. Most of the rhythms only have six to eight drum parts, so the class must also learn the dances and the songs which go with them. The Cuban class is a little harder than the Escola de Samba as it takes time to get a decent sound out of the hand drums, while in the Samba class all the instruments are played with a stick or mallet so you can have many players on each part.

“I teach bell, kata (woodblock), (gourd shaker) and tumbadora (conga drum) parts, one learner on a part. Class A is doing Palo, Guanguanco, and Bata Toque Yesa, all with songs and dance. They are also performing Comparsa, the Cuban carnival rhythm, with songs and dance.”

Lazar concludes: “In Class B we learn the makuta along with dances and five different songs, including and. We’re also performing [originally ceremonial music] from the santeria tradition along with several songs. Most of these songs are in the Yoruba language and students learn the lyrics phonetically.”

Irene Markoff, Balkan Music Ensemble director

I asked the ethnomusicologist, musician, conductor and veteran York U. lecturer and ensemble instructor about her geographically inclusive course:

“We cover music from the Balkans (Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia, Macedonia, Bulgaria, Greece, Albania),” Markoff wrote, “as well as Azerbaijan and Turkey (a better part of the Balkans were a part of the Ottoman Empire for almost 500 years). We also perform Kurdish music from Iran, music of the Roma, and a little repertoire from Iran, as I often have Iranian students in my ensemble.

“This year there’s a Greek student in the class who helps with Greek pronunciation and also two Iranian students who help with Farsi pronunciation. I transcribe and arrange music for the ensemble according to the instruments the students play and sometimes teach vocal music by rote as that is the way the repertoire would be taught in the village context.

we will perform repertoire from all the countries I mentioned including Ederlezi by Goran Bregovic, based on a .”

Markoff sees the debate about terminology this way: “I don’t have a problem with the term as it has been used and accepted by ethnomusicologists and universities for many years now. In a general sense world music means music of the world’s cultures.

“Also, there is a lot of hybridity happening in countries such as Turkey these days. Folk music ensembles seen on national TV and elsewhere include Western instruments such as acoustic/electric guitars and electric bass guitars, adding harmony to a music that was essentially monophonic [and modal]. … What do we call that music then?

As for other candidates for an accepted term, Markoff notes: “Finding a general cover term is problematic … You may be aware that in the past other terms used were ‘primitive,’ ‘non-Western,’ ‘ethnic’ and ‘folk.’ Some have suggested ‘roots’ and ‘local.’ I don’t believe that any of those are appropriate overall terms.”

University Of Waterloo Balinese Gamelan Ensemble

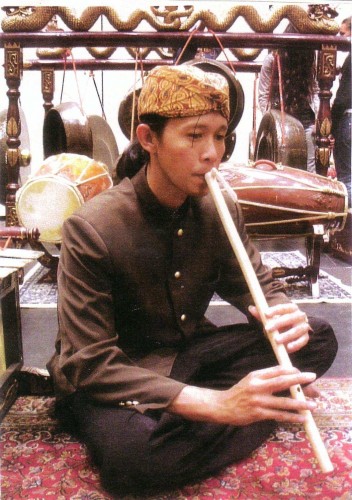

April 3, the UW Balinese Gamelan and the Grebel Community Gamelan perform at the Humanities Theatre, University of Waterloo. Ethnomusicologist Maisie Sum introduced world music ensembles at UW in Waterloo ON in 2013 with a Balinese gamelan semaradana course.

Directed by Sum and featuring Grebel artist-in-residence I Dewa Made Suparta, the Balinese gamelan will perform a mix of contemporary and traditional Balinese repertoire. As they did last year, they may include Balinese dance in the concert, a near-essential performative ingredient in Bali. After the free concert the audience is invited to try their hand playing the instruments.

University of Toronto’s World Music Ensembles Concert

April 6 at 2:30pm, University of Toronto Faculty of Music presents its World Music Ensembles at Walter Hall, Edward Johnson Building, University of Toronto. Directing their groups are Ghanaian master drummer Kwasi Dunyo, Steel Pan Ensemble director Joe Cullen, and Alan Hetherington directing the Latin American Ensemble.

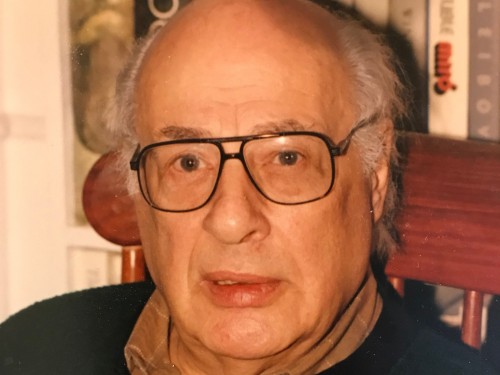

While I was unable to reach these instructors before press time, this time round, I was able to connect with percussionist and composer Mark Duggan. Active on Toronto’s world music, jazz and classical concert music scenes for decades, he’s taught ensembles at Humber College as well as at U of T, with a specialty in Brazilian musics. He’s taking a sabbatical from U of T this year, but generously weighed in on the topic.

“Unfortunately, the term ‘world music’ does serve to hegemonize all music traditions outside the Western mainstream,” he said, “so these days I choose to not use it. My students do use world music freely to refer to a plethora of different styles of traditional and/or hybrid musics, including pop and jazz. [But I believe] the term has outlived its usefulness.”

Judith Cohen, World Music Performer

Judith Cohen, World Music Performer

Ethnomusicologist, musician and long-time York University faculty Judith R. Cohen is also very active as a world music performer. March 16, Alliance Française Toronto presents “Judith Cohen & her guests: Women of the World” at the AFT’s Spadina Theatre with Kelly Lefaive (vocals, violin, mandolin, guitar), Naghmeh Farahmand (Persian percussion), Veronica Johnny (Indigenous hand drummer, vocals) and other surprise guests.

I emailed Cohen about my topic of the month, and she wryly replied, “Haven’t noticed anyone making music who is not part of the world. And what are the alternatives? ‘Global’? And the difference between the world and the globe is…?”

She was just returning from the February ethnomusicology summit at the Folk Alliance International Conference (FAI) in Montreal. The FAI held a panel critiquing “world music.” However, “We did not end up condemning the term, even though FAI dropped it some years ago,” Cohen noted.

Moreover, she doesn’t see the benefit of yet another moniker. “Commercial showcases such as FAI and WOMEX are going to market, brand and sell no matter what term people come up with. Is ‘culturally diverse’ a candidate for replacing that increasingly (and needlessly, I think) shamed term ‘world music’? It sure doesn’t have the marketing zip of ‘world,”’ Cohen concludes.

So what’s the future of culturally diverse music teaching and performance in Ontario music education?

Irene Markoff is encouraged: “York U [Department of Music] is now trying to find ways to draw more music majors to the world music ensembles, which is a good sign. … I believe that any Ontario music university student who has a desire to teach at the public or high school level should be required to take a few world music ensemble classes when offered. That would prepare them to meet the challenges of cultural diversity in the classroom.”

Rick Lazar adds: Mark Duggan gets the last word among these contributors in our discussion: “The reality is that we have to start referring to specific styles of music or specific regions with their proper names, the names that the creators and purveyors of those traditions use. I think the next step is to stop exoticizing non-Western musics and put them on equal footing with privileged traditions. Like integration in a multicultural society, that means giving them equal space in music schools, or perhaps creating schools that specialize in one or more non-Western traditions without including any European classical perspectives.”

At the same time as we reach toward increasing diversity, entrenched attitudes remain in music education – as in other reaches of our society – which marginalize certain musics, particularly non-Eurocentric ones, such as Indigenous voices. What music is “ours”? And what place should so-called “other” musics have in our music education today?

These are bracing, far-reaching questions.

Footnote:

Regular readers of this column over the years will know that this is not the first time I have delved into aspects of these topics. My September 2018 column Rebooting the Beat: Thoughts on the “World Music” Tag explored the implications of the 1962 and 1987 disparate points of entry for the “world music” tag. For more on the spread of world music as a discipline in Canada, see my March 2016 column, York Music’s World Class Role. And for more insights into the Waterloo Balinese Gamelan Ensemble, see my April 2014 conversation with ethnomusicologist Maisie Sum in Smartphone Serendipity Not The Only Way.

This column has been revised (March 12) to accurately reflect Judith R. Cohen's current teaching status at York University.

Andrew Timar is a Toronto musician and music writer. He can be contacted at worldmusic@thewholenote.com.