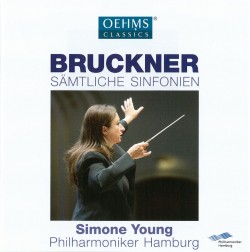

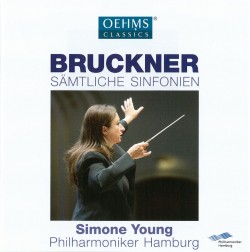

Bruckner – Samliche Sinfonien (Symphonies 1–9; Student Symphony; Symphony “0” – Original versions)

Bruckner – Samliche Sinfonien (Symphonies 1–9; Student Symphony; Symphony “0” – Original versions)

Philharmoniker Hamburg; Simone Young

Oehms Classics OC 026

The legendary Sergiu Celibidache, perhaps the greatest Bruckner conductor ever, once said: “Time for the average person begins at the beginning, but for Bruckner time begins after the last note has been heard.” This distinguishes his music from, say, Beethoven or Brahms which moves logically from beginning to end. A Bruckner symphony must be heard in its entirety to begin percolating through one’s senses with the full effect emerging from the subconscious, sometimes as a jolt like the conversion of Saul on the road to Damascus. Bruckner is in no hurry. He ambles along at a leisurely pace, often stopping for breath or a backward glance. His music is “elemental rather than intellectual, it is hypnotic and incantatory” (Richard Capell). A great live performance could be breathtaking and cataclysmic.

This new set of complete Bruckner symphonies has been released one by one over the past few years and reviewed extensively by the most respectable music journals to rave reviews. After listening to every single one of them I most emphatically concur; in fact it’s been hard to contain my enthusiasm. And the conductor? Simone Young, a young lady from Sidney, Australia, who arrived in Germany in her 20s and quickly became assistant to Daniel Barenboim at the Berlin Staatsoper and soon thereafter took over the entire musical life of Hamburg (i.e. the Symphony and the Opera that dates back to the 17th century under such directors as Telemann, Gluck, Handel, Bulow, Mahler and a list of venerable conductors like Klemperer, Wand and Nagano). Now, this already indicates an extraordinary and enormously gifted musician, but a first foray into the recording world with a statement on one of the most complex and difficult composers, Bruckner (who conductors have spent a lifetime studying and struggling to interpret) is a feat no less than miraculous. Notable also that she opts for the original versions (Urfassung) unlike most other conductors who use one of the many revised versions. Minor point, but Symphony No.4 is completely unrecognizable in its original form; the 1880 version is the way it’s always performed and as such is sadly missing from this set.

Bruckner’s oeuvre divides itself into three categories, the early symphonies (1 - 4), the middle period (5 and 6) and the final masterworks (7, 8 and 9). Symphony No.1 is youthful, tempestuous, strongly rhythmic and then there is a curiosity, Symphony 0, a piece Bruckner rejected as “not good enough” so it became known as the Die Nullte (annulled) but luckily survived. Both of these are driven joyfully with exuberance, very un-Bruckner as it were, but in the Third Symphony (1873, D Minor) Young passes the first real hurdle with great aplomb showing youthful lightheartedness in the lovely Scherzo that really dances; it’s an absolute delight. The second movement with its Tristan quotations is majestically developed with beautiful lyricism and an almost Schubertian joy in melodies. The fourth movement is fast and turbulent, exciting and suspenseful with a nice Brucknerian finale.

As we now enter the middle period there is a quantum leap in Bruckner’s output and although he keeps to his original format the music is entirely different like the giant Fifth Symphony of churchlike solemnity and unheard-of complexity. A real stumbling block for conductors, it is rarely performed but – and here comes the miracle – she is simply magnificent. “Probably the finest [new performance] I’ve heard for a long time…Young manages the rare feat of honouring all Bruckner’s changes of gear and tempo while keeping a powerful forward flow…no doubt I shall listen to other accounts which are as fine, but for the moment I find that hard to believe” (BBC Music Magazine, December 2015). I would love to watch her do the giant fugue of the last movement at the helm of the thundering orchestra like a Napoleon commanding his armies. And what made Napoleon able to conquer most of Europe was not the size of his armies, but his uncanny ability to manipulate his troops and outwit the enemy, much the same as what Young does. With a tremendous insight and overview of the score she always has the ending in sight and by shifting the emphasis of the thematic material the progress is kept interesting, never boring.

The last three symphonies are the pinnacle of Bruckner’s art and this is where Young brings out the big guns. The unfinished, enigmatic and otherworldly Ninth with its valedictory Adagio is simply musical heaven and the greatest thing he ever wrote, but the monumental 90-minute long Eighth Symphony, being 100 percent complete, is also an incredibly satisfying, glorious work to which she brings grace and lightness in the Scherzo, and a hushed intensity to the Largo like a long, long prayer with a single earth-shattering fortissimo climax achieved after a long sustained crescendo of some 22 minutes. Big guns, indeed. Unhesitating recommendation.

Freedom of the City

Freedom of the City