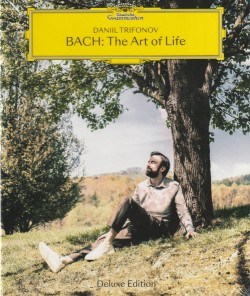

Bach – The Art of Life - Daniil Trifonov

Bach – The Art of Life

Bach – The Art of Life

Daniil Trifonov

Deutsche Grammophon 073 6270 (deutschegrammophon.com/en/artists/daniil-trifonov/daniil-trifonov-bach-the-art-of-life-2062)

While the term ambitious is perhaps an overused descriptor for musical recordings (or anything else artistic for that matter), the adjective most certainly rings true for Daniil Trifonov’s 2022 Deutsche Grammophon release: Bach: The Art of Life. Spanning two CDS with liner notes by Oscar Alan, plus an extensive live concert Blu-ray disc, the recording provides a welcome window into comprehensive, sublime and historically accurate Baroque solo piano playing (in as much as anything originally written for the harpsichord or organ but played on the piano could be historically accurate)! That aside, this recording beautifully mines the music of the family Bach (J.S., of course, but also W.F., C.P.E. and J.C.) proving, at least musically, E.O. Wilson’s famous aphorism: “genes hold culture on a leash.”

If, as the German musicologist Carl Dahlhaus pronounced, the 19th century belonged to Beethoven and Rossini (so much so that Johannes Brahms equated composing post-Beethoven to hearing “the tread of a giant behind him”), how then must it have felt to be a composer (not to mention, “son of”) following the supreme legacy left by patriarch Bach? And although this recording is centred around the elder’s Art of the Fugue, all the pieces featured here, father or sons notwithstanding, are given equal heft and import, and are dealt with rigorously by Trifonov (who up to this point has not necessarily been known for his Bach playing) in a manner that is egalitarian, rather than lesser than, and with a keyboard touch that one hopes will bring these deserving works more in line with the ever-expanding canon of Western art music.