Whither Art Song? An Immodest Proposal

On a pleasantly cold February evening, Toronto Masque Theatre held one of its last shows. It was a program of songs: Bach’s Peasant Cantata in English translation, and a selection of pop and Broadway numbers sung by musician friends. An actor was on hand to read us poems, mostly of Romantic vintage. The hall was a heritage schoolhouse that could have passed for a church.

The modestly sized space was filled to the last seat and the audience enjoyed the show. I noticed though what I notice in a lot of other Toronto song concerts – a certain atmosphere of everybody knowing each other, and an audience that knows exactly what to expect and coming for exactly that.

I was generously invited as a guest reviewer and did not have to pay the ticket, but they are not cheap: $40 arts worker, $50 general audience, with senior and under-30 discounts. And the way our arts funding is structured, this is what the small-to-medium arts organizations have to charge to make their seasons palatable. Now, if you were not already a TMT fan (and I appreciate their operatic programming and will miss it when it’s gone), would you pay that much for an evening of rearranged popular songs and a quaint museum piece by Bach?

The stable but modest and stagnating audience is the impression I get at a lot of other art song concerts in Toronto. Talisker Players, which also recently folded, perfected the formula: a set of readings, a set of songs. Some of their concerts gave me a lot of pleasure over the last few years, but I knew exactly what to expect each time. Going further back, Aldeburgh Connection, the Stephen Ralls and Bruce Ubukata recital series, also consisted of reading and music. It also folded, after an impressive 30-year run. It was largely looking to the past, in its name and programming, and it lived in a cavernous U of T hall, but it could have easily continued on and its core audience would have continued to come. Stable audience, yes, but also unchanging.

The issue with a stable and unchanging audience is that the programming will suffer. It’ll go stale, ignore the not already converted, abandon the art of programming seduction. And the ticket will still cost at least $50.

I’ve also sat in the Music Gallery’s contemporary music recitals alongside the audience of eight so it’s not entirely the matter of heritage music vs. new music. Empty halls for contemporary music concerts are as depressing as book events in Toronto, to which nobody, not even the writer’s friends, go. (I know this well; don’t ask me how.)

So, where is art song performance in Canada’s largest city going?

Due to the way they’ve been presented for decades now, there’s a not-negligible whiff of Anglican and Methodist churchiness to Toronto’s art song concerts. They usually take place in a church (Trinity-St. Paul’s, Rosedale United, Trinity Chapel, St. Andrew’s, etc) or a place very much like a church (Heliconian Hall). They are often programmed as an occasion for personal edification – as something that’ll be good for you, that will be a learning opportunity. Why are we being read to so much in recitals – instead of, for example, being talked to and with? Does anybody really enjoy being read to in a music concert?

I sometimes wonder if the classical music infrastructure of concertgoing, its comportment etiquette, regulation of space, fussy rituals of beginning, presentation, breaks and ending wasn’t built to control and disguise classical music’s visceral power over humans? And to keep tame its community-expanding, boundary-blurring potential?

In other words, getting out of the church and the U of T will benefit Toronto’s art song performance. Classical music, including art song, is a pleasure, not homework; it’s inviting the stranger over, not getting together with the same group each time. Some of those who program art song and chamber music in Toronto are already grappling with these questions, fortunately.

Collectìf

Among them is the ensemble Collectìf, consisting of three singers and a pianist: Danika Lorèn, Whitney O’Hearn, Jennifer Krabbe and Tom King. They scour the city for locations and choose places off the beaten path. They held a recital in an Adelaide St. W. loft, and a raucous songfest at an old pub in Little Italy. For a Schubert Winterreise, performed in the more familiar quarters of Heliconian Hall, Danika Lorèn had prepared video projections to accompany the performance and the singing was divided among the three singers, who became three characters. For an outing to the COC’s free concert series, they created their own commedia dell’arte props and programmed thematically around the poets, not the composers who set their poems to music. Collectìf is a shoestring operation, just starting out, yet already being noticed for innovation. Lorèn is currently member of the COC’s Ensemble Studio, which is why the Collectìf somewhat slowed down, but when I spoke to her in Banff this summer, she assured me that the group is eager to get back to performing. Winterreise toured last fall to Quebec and an art song program around the theme of nightmares returns to the same festival later in the year.

Happenstance

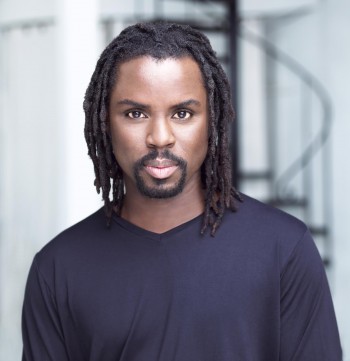

Another group that caught my eye did not even have a name when I first heard them in concert. They are now called Happenstance, the core ensemble formed by clarinettist Brad Cherwin, soprano Adanya Dunn and pianist Nahre Sol. That’s an obscene amount of talent in the trio (and check out Nahre Sol’s Practice Notes series on YouTube), but what makes them stand way out is the sharp programming that combines the music of the present day with musical heritage. “Lineage,” which they performed about a year ago, was an evening of German Romantic song with Berg, Schoenberg, Webern and Rihm and not a dull second. A more recent concert, at the Temerty Theatre on the second floor of the RCM, joined together Françaix, Messiaen, Debussy, Jolivet and Dusapin. The evening suffered from some logistical snags – the lights went down before a long song cycle and nobody but the native French speakers could follow the text – but Cherwin tells me he is always adjusting and eager to experiment with the format.

Cherwin and I talked recently via instant messenger about their planned March concert. As it happens, both the pianist and the clarinettist have suffered wrist injuries and have had to postpone the booking for later in March or early April. Since you are likely reading this in early March, reader, head to facebook.com/thehappenstancers to find out the exact date of the concert.

In the vocal part of the program, there will be a Kurtág piece (Four Songs to Poems by János Pilinszky, Op.11), a Vivier piece arranged for baritone, violin, clarinet, and keyboards, and something that Cherwin describes as “structured improv involving voice”. “It’s a structured improv piece by André Boucourechliev that we’re using in a few different iterations as a bridge between sections of the concert,” he types.

In the vocal part of the program, there will be a Kurtág piece (Four Songs to Poems by János Pilinszky, Op.11), a Vivier piece arranged for baritone, violin, clarinet, and keyboards, and something that Cherwin describes as “structured improv involving voice”. “It’s a structured improv piece by André Boucourechliev that we’re using in a few different iterations as a bridge between sections of the concert,” he types.

I tell him that I’m working on an article on whether the art song concert can be exciting again, and he types back that it’s something they’ve been thinking about a lot. “How can we take everything we love about the chamber music recital and take it to a more unexpected place. How can repertoire and presentation interact to create a narrative/context for contemporary music. How can new rep look back on and interact with old rep in a way that enhances both?”

He tells me that they’re looking into the concert structure at the same time – so I may yet live to see recitals where the pieces are consistently introduced by the musicians themselves.

Will concerts continue to involve an entirely passive audience looking at the musicians performing, with a strict separation between the two? There were times, not so long ago, when people bought the published song sheets to play at home and when the non-vocational (better word than amateur) musicianship enhanced the concert-goers’ experience of music. Any way to involve people in the production of at least a fraction of the concert sound or concert narrative?, I ask him, expecting he’ll politely tell me to find a hobby.

“We’ve thought a lot about that actually,” he types back. “It’s a difficult balance. Finding a way to leave room for collaboration while also having a curated experience.” Against the Grain Theatre, the opera company where he now plays in the permanent ensemble, also wants to push in that direction, he tells me.

Boldly Go

There is a corner of the musical avant-garde, it occurs to me as I thank him and log off from our chat, that actively seeks out non-professional participation. There are Pauline Oliveros’ tuning meditations, of course, but more locally there is also Torontonian Christopher Willes, whose various pieces require participation and are fundamentally collective and collaborative. Though he isn’t a musician, Misha Glouberman’s workshops in social behaviour, like Terrible Noises for Beautiful People, are arguably a process of music-making.

But how to achieve an active audience in the small, chamber or lieder situations? It’s easier with choruses and large production, where sing-alongs are possible – some smaller opera houses are already doing it, for example Opéra-Comique in Paris. The Collectìf trio did get the audience to sing at the Monarch Tavern that one time (the Do Over, January 2016) but the experiment hasn’t been repeated in Toronto.

Speaking of pub recitals, Against the Grain’s Opera Pub is a glorious project (first Thursday of every month at the Amsterdam Bicycle Club), but it’s more operatic than art song, at least for now. ClassyAF are a group of instrumentalists who perform in La Rev and The Dakota Tavern, no vocals. Drake One Fifty restaurant in the Financial District has just started the Popera Series with opera’s greatest hits performed in a restaurant full of people, but again, it’s opera, the more glamorous and easier-to-sell sibling to the art song.

Will Happenstance, Collectif and similar innovative upstarts, and their more established peers like Canadian Art Song Project, endure over the years, obtain recurring arts council funding and renew art song audience?

Will Happenstance, Collectif and similar innovative upstarts, and their more established peers like Canadian Art Song Project, endure over the years, obtain recurring arts council funding and renew art song audience?

With that goal in mind, my immodest proposal for the present and future art song presenter: move out of the churches and university halls. Musicians, talk to people, introduce the pieces. Program the unfamiliar. Always include new music, maybe even by composers who can be there and say a few words. If the music is danceable, allow for concerts with audience dancing. (I’m looking at you, Vesuvius Ensemble.) Engage the people. If live music is to be different from staring at the screen, make it different from staring at the screen.

Some March highlights

Meanwhile, here are my March highlights, which are of the more traditional Toronto kind, though still of interest.

March 19 at 7:30pm, Canadian Art Song Project presents its 2018 commission, Miss Carr in Seven Scenes by Jeffrey Ryan. Miss Carr is Emily Carr, and the song cycle, based on her journals, was written for Krisztina Szabó and Steven Philcox. At (alas) U of T’s Walter Hall.

March 4, as part of Syrinx Concerts Toronto, mezzo Georgia Burashko will sing Grieg’s Lieder with Valentina Sadovski at the piano. Baritone Adam Harris joins her in Schumann duets for baritone and mezzo, whereas solo, he will sing Canadian composer Michael Rudman’s The City.

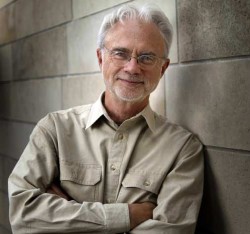

March 11 at Temerty Theatre, Andrea Botticelli will give a lecture-recital (I like the sound of this) on the Koerner collection, “Exploring Early Keyboard Instruments.” Vocal and keyboard works by Purcell, Haydn and Beethoven on the program with tenor Lawrence Wiliford singing. The only U of T chapel to which I will always gladly return, the Victoria College Chapel, hosts the Faculty of Music’s Graduate Singers Series, also on March 11.

Finally, if you are in Waterloo on March 7 and up for some Finnish folk, the U of W’s Department of Music presents the EVA-trio (cellist Vesa Norilo, kantele player Anna-Karin Korhonen and soprano Essi Wuorela) in a noon-hour concert.

Am I wrong about the future of art song in Toronto? Send me an email at artofsong@thewholenote.com.