Review: With “Clara – Robert – Johannes”, the NAC Orchestra draws 19th-century connections

![]() This article appears in The WholeNote as part of our collaboration in the Emerging Arts Critics program.

This article appears in The WholeNote as part of our collaboration in the Emerging Arts Critics program.

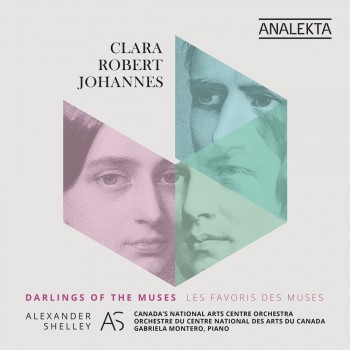

Clara - Robert - Johannes: Darlings of the Muses

Clara - Robert - Johannes: Darlings of the Muses

Alexander Shelley, Canada's National Arts Centre Orchestra, Gabriela Montero (piano)

Analekta AN288778

We sometimes think of 19th-century composers as solitary souls, confined to a dimly lit room with a pen, paper and piano. But often, they were part of a community of artists and friends who inspire one another’s creative processes. This was especially, and famously, true for the Romantic-era trio of Robert Schumann, Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms, whose lives were inextricably linked through a web of shared experiences and a bond between Clara Schumann and Brahms that spanned nearly five decades. Robert Schumann and his wife Clara Schumann were mentors to the younger Brahms. Following Robert Schumann’s death, Clara Schumann and Brahms formed a strong friendship that continued until Clara’s own death (whether their relationship was anything more than a friendship continues to be debated among music historians).

The trio’s exchange of artistic ideas is the central focus of the National Arts Centre (NAC) Orchestra’s latest album Clara - Robert - Johannes: Darlings of the Muses (Analekta), the first in a series of four albums exploring the personal and musical connections between the three artists. Darlings of the Muses pairs the two first symphonies of the men – Robert Schumann’s “Spring” Symphony No. 1 in B-Flat Major Op. 38 with Johannes Brahms’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor Op. 68 – and adds Clara Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A Minor Op. 7. The album is rounded out with five mesmerizing improvisations by Venezuelan pianist Gabriela Montero, based on themes from Clara Schumann’s work.

The recording begins with Robert Schumann’s Symphony No. 1, a fine example of Romantic-era composition filled with all the characteristics of music from that time – dense chromatic runs, lyrical melodies that sweep across the instruments of the orchestra and dramatic tempo and dynamic changes. The idea of spring is peppered throughout Robert Schumann’s voluptuous score: at the top of the first movement, a roaring brass entrance announces the arrival of warmer days, trills in the flutes depict chirping chicks ready to take flight, and rhythmic patter from the violas serves as the ominous reminder of an imminent storm. The orchestra, under the direction of conductor Alexander Shelley, takes a restrained tempo. But in Shelley’s hands, this is a welcome trade-off, for every dynamic contrast is highlighted and every musical phrase is contoured to create beautiful lyricism – details which may otherwise be overlooked in a brisker interpretation.

It is fitting that this piece is followed by Clara Schumann’s Piano Concerto, which is the centrepiece of the album. She was arguably the composer who had the greatest influence over the other members of the trio, inspiring and helping both her husband and Brahms compose their first symphonies. The Piano Concerto itself is a remarkable achievement, especially given that Clara Schumann was merely 16 years old when she completed the piece. It is also an incredible vehicle for a pianist to display their virtuosity – and in this recording, Montero makes full use of that opportunity. She plays the opening chords with such verve and robust energy that it makes the subsequent single-line melody sound all the more graceful as it gently floats above a dark murmur of strings. Montero’s compelling technical and emotional range is expressed throughout the entire concerto, but is especially apparent in the Romanze, when the initial melody from the first movement is transformed into a silvery, meditative duet for piano and cello (a wonderful Rachel Mercer). The final movement features a recapitulation of this theme, now heavier and more laboured. Montero strikes each note with a power that continues to grow incessantly until the final sustained chord.

The Piano Concerto is bookended with short improvisations by Montero, who is well-known for her improvisational work based on audience suggestions and themes from classical pieces. Before listening to this album, I felt that it was wrong to record improvisations; for me, they are ephemeral dialogues between an artist and a live audience that are not meant to be seared onto a permanent recording. But this album is an exception. It captures the exquisite intimacy of these jewel boxes of improvisations and Montero’s delicate touch, which evokes a sense of pensive reflection. Her creations – gentle atmospheric lullabies with melancholic melodies and undulating chords – faintly resemble Clara Schumann’s style. The way they organically grow from silence and wistfully fade off into nothingness is magical.

Brahms’s Symphony No. 1 follows Montero’s exquisite works and closes out the album. It begins on a sombre tone, with the strings sustaining long chords in syncopated rhythms, while the timpani cuts through with a series of relentless pulsing notes. As with Robert Schumann’s symphony, Shelley also takes a restrained tempo in this piece. But here, it results in a lack of forward momentum that is especially needed in the strings’ lively sixteenth-note runs. It is not until the final moments of the fourth movement – when the multiple melodies coalesce into a singular rhythmic drive to the finish, accompanied by the rumbling timpani – when that much-needed momentum finally begins to appear.

In spite of this shortcoming, the power of this album is in its ability to capture the listener’s imagination and inspire them to find connections between the works of these three musical giants. If this is the quality of the future albums in this series, we have a treat in store.

The National Arts Centre Orchestra released Clara – Robert – Johannes: Darlings of the Muses (Analekta) on May 8, 2020.

Joshua Chong is in his fifth year at North Toronto Collegiate Institute. For the past five years, he has been a student journalist for his school’s award-winning newspaper, Graffiti. He is also an avid violinist and violist.