Through the years, jazz in Hamilton has often been overshadowed by the bigger scene in Toronto, just as Toronto jazz has been dwarfed by the huge and active scene in New York. Part of it has to do with economics and sheer size, as jazz, not being a popular music for some time, has always required a large population base in order to flourish. Generally, the bigger the city, the bigger and better its jazz scene. While all sorts of jazz musicians have come from very small towns, they have cut their musical teeth either on the road or by moving to bigger cities. Part of it also has to with Toronto tending to see itself as the centre of the universe, as many big cities do.

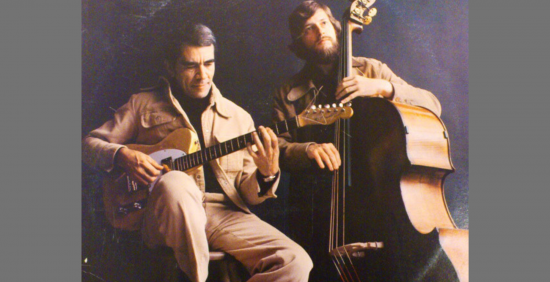

None of this has been fair to Hamilton, which has had its own interesting jazz scene for many years and continues to. For one thing, Hamilton, like its steel-producing sister city Pittsburgh, has produced a remarkable number of significant jazz musicians for a city its size. For example, guitarist Sonny Greenwich is from Hamilton, and it’s hard to think of a more singularly original voice in the entire history of Canadian jazz. Granted, like musicians from Pittsburgh who gravitated to New York in search of more work, Greenwich settled in Toronto and later Montreal, but he got his start in Steeltown.

So did saxophonist/arranger Rick Wilkins, another hugely important figure in Canadian music, jazz and otherwise. Being so quiet and mild-mannered, Rick is perhaps the ultimate insider in Canadian music. By this I mean that one could randomly pick 100 people on the street aged 60 or older and ask them if they’d heard of Rick Wilkins and maybe one or two would answer yes. But all of them would have heard lots of his music in some form – a saxophone solo with the Boss Brass, countless scores for television or movies, an arrangement on somebody’s record, a jingle – often without realizing it. Most of his career has taken place in Toronto, but he was born in Hamilton. Torontonians who are boastfully proud of their city’s rich jazz history would do well to remember that an awful lot of the major contributors have come from somewhere else – Vancouver, Winnipeg, Northern Ontario, Quebec, the Maritimes and yes, Hamilton.

A more recent example is pianist/composer David Braid, who has had a major impact with his sextet, the more recent quartet, The North, and as a composer and educator. He grew up not far from Mohawk College in Hamilton and, as much as any Canadian jazz musician, has taken his music abroad with frequent tours in China, Russia, Europe and elsewhere. There have been other important Hamilton-born jazz players – pianist Bruce Harvey, two excellent trumpeters in Jason Logue and Steve McDade, and no doubt many others I’ve forgotten or overlooked.

A more recent example is pianist/composer David Braid, who has had a major impact with his sextet, the more recent quartet, The North, and as a composer and educator. He grew up not far from Mohawk College in Hamilton and, as much as any Canadian jazz musician, has taken his music abroad with frequent tours in China, Russia, Europe and elsewhere. There have been other important Hamilton-born jazz players – pianist Bruce Harvey, two excellent trumpeters in Jason Logue and Steve McDade, and no doubt many others I’ve forgotten or overlooked.

Mohawk and more

The jazz program at Mohawk College has had a major impact as a centerpiece of jazz in Hamilton in several ways. It draws talented young players from the surrounding region, provides a venue for concerts and has attracted, as teachers, important musicians, some of them previously Toronto-based, who have raised the level and profile of jazz in Hamilton in recent years.

Some musicians who were full-time faculty, such as the late trombonist Dave McMurdo and trumpeter Mike Malone, moved to Hamilton from Toronto, reversing an age-old tradition. McMurdo had a huge impact on Hamilton jazz as a teacher and by starting his Mountain Access (sometimes affectionately known as “Mounting Excess”) Jazz Orchestra, which provided an outlet for writers and players both from Toronto and the Hamilton area. Malone has continued this with his Writer’s Jazz Orchestra, which performs regularly in and around Hamilton and at Toronto venues such as The Rex. More recently, the Hamilton-born, gifted pianist Adrean Farrugia and his equally gifted wife, singer Sophia Perlman, who both teach at Mohawk, have moved from Hogtown to Steeltown, perhaps attracted by a city that’s less hectic, more affordable, and still offers opportunities for cultural expression. With the Toronto jazz scene shrinking in recent times, the worm is beginning to turn toward smaller cities.

Some musicians who were full-time faculty, such as the late trombonist Dave McMurdo and trumpeter Mike Malone, moved to Hamilton from Toronto, reversing an age-old tradition. McMurdo had a huge impact on Hamilton jazz as a teacher and by starting his Mountain Access (sometimes affectionately known as “Mounting Excess”) Jazz Orchestra, which provided an outlet for writers and players both from Toronto and the Hamilton area. Malone has continued this with his Writer’s Jazz Orchestra, which performs regularly in and around Hamilton and at Toronto venues such as The Rex. More recently, the Hamilton-born, gifted pianist Adrean Farrugia and his equally gifted wife, singer Sophia Perlman, who both teach at Mohawk, have moved from Hogtown to Steeltown, perhaps attracted by a city that’s less hectic, more affordable, and still offers opportunities for cultural expression. With the Toronto jazz scene shrinking in recent times, the worm is beginning to turn toward smaller cities.

Hamilton has also boasted attractive musical venues and organizations through the years, often created and sustained by dedicated music lovers and arts activists. Liuna Station is an excellent example. It was originally a CN Railway station which had fallen into disrepair until a guild of local artisans was commissioned to give it a lavish facelift. The result is a unique and splendid venue for concerts as well as other functions. I’ve played there numerous times with the likes of Oliver Jones and David Braid and was bowled over by its extravagance. One of my favourite places to play in Hamilton was not really a jazz venue but a small Polish restaurant on Main St. called Izzy’s, named for its cheerful and generous proprietor Isidora, who loved jazz, cooking, jazz musicians and Irish whiskey, not necessarily in that order. I’ll never forget playing there one night with the Mike Murley Trio when Kenny Wheeler, Norma Winstone, Dave McMurdo and Mike Malone were in the audience. Wheeler and Winstone were in Hamilton as artists-in-residence for a week of clinics and concerts at Mohawk College, another example of how that institution has boosted jazz in Hamilton.

Steel City Jazz Festival

Hamilton boasts many other long-term jazz outlets – the Corktown Pub, Artword Artbar (on which more later), Fieldcote Park in nearby Ancaster, The Pearl Company, as well as concert venues at Mohawk College and McMaster University. Hamilton has also staged its own festival for the last seven years, The Steel City Jazz Festival. This year’s festival runs from November 6 to 10 and will feature shows at Artword Artbar, the Corktown Pub and The Pearl Company. It will return to its roots by showcasing pianist Paul Benton, a longtime seminal figure in Hamilton jazz, in its opening concert, and by focusing on the past 30 years of jazz in the area.

Other artists will include the Nick McLean Quartet, the Sextet of Smordin Law artist-in-residence Jason Logue, the Waleed Kush African Jazz Ensemble and Mike Malone, playing as part of the ECJ quintet led by bassist Evelyn Charlotte Joe. This year the festival is also launching performances at the legendary Corktown Pub – George Grossman’s Bohemian Swing featuring Brandon Walker on November 7 and Blunt Object on November 8. It’s a diverse and interesting lineup.

Farewell Artword, hail Zula

Unfortunately, this year’s festival will mark the end of one of Hamilton’s best music venues, Artword Artbar, a café-bar on Colbourne Street which has been hosting jazz and other interesting music and theatre for the past ten years. Proprietors Ronald Weihs and Judith Sandiford have sold the building and its future use is unclear, but it won’t likely have to do with music or the arts. This is a decided blow to the local scene and one hopes someone will step in with an alternative space at some point. I only played there once, some years ago with the Mike Murley Trio, and very much enjoyed the experience. Artword Artbar has (had) good natural sound and a relaxing, casual, grassroots feeling which combined the best of both worlds – a small concert space and a rustic pub – one which encouraged audiences to listen and inspired artists to play their best. It will be missed.

But not all is lost… finally, a word on another force in Hamilton jazz, one largely unknown to many Torontonians, including yours truly until recently: Zula, a bold and independent arts organization dedicated to presenting adventurous and under-the-radar music against long odds in Hamilton. It is the brainchild of music lover and arts activist Cem Zafir, who originally founded Zula in Vancouver way back in 2000, transplanting the concept to Hamilton when he moved there in 2012. It is supported by the Ontario Arts Council and has gathered a board of local artists including Donna Akrey, Chris Alic, Neil Ballantyne, Gary Barwin, Ted Harms, Connor Bennett, Taing Ng-Chan, Kay Chornook, Andrew Johnson, Heather Kanabe, Neal Thomas and above all Zafir, whose non-conformist and creative spirit is the driving force behind it all.

Since 2014, Zula has staged the Something Else Festival, presenting under-known and adventurous musicians from Canada and abroad who one would never expect to hear in Hamilton, never mind a larger city like Toronto. Such as William Parker, Samuel Blaser, Dave Gould, the Lina Allemano Four, David Lee, Ken Aldcroft and many more. Zula often coordinates with the equally adventurous Guelph Jazz Festival, another good example of uncompromising music flourishing in a smaller population centre against long odds, largely due to the vision and dedication of its founders.

So, as we’ve seen, bigger is not always better and jazz continues to grow in Hamilton, with all signs indicating that it will continue to.

JAZZ NOTES QUICK PICKS

NOV 2, 8PM: Royal Conservatory of Music. “Music Mix Series: Toronto Sings the Breithaupt Brothers’ Songbook.” Jackie Richardson, Kellylee Evans, Denzal Sinclaire, Heather Bambrick, Patricia O’Callaghan and others. Koerner Hall. A lineup of first-rate Canadian singers performing the witty and artistic songs of the Breithaupt Brothers.

NOV 8, 7:30PM: Bravo Niagara! Festival of the Arts. Monty Alexander’s Harlem-Kingston Express and Larnell Lewis Band. Works by Monty Alexander and Larnell Lewis. Monty Alexander, piano; Hassan Abdul Ash-Shakur, bass; Jason Brown, drums; Andrew Bassford, guitar; Larnell Lewis Band. FirstOntario Performing Arts Centre Partridge Hall, 250 St. Paul St., St. Catharines. An attractive doubleheader featuring Monty Alexander, who needs no introduction, and local drummer Larnell Lewis, who has become something of a force in recent years.

NOV 21, 7:30PM: Ken Page Memorial Trust. Jim Galloway’s Wee Big Band. 40th Anniversary celebration of swing-era music with special selections from Duke Ellington and Count Basie. Martin Loomer, guitar, arranger, leader. Arts and Letters Club, 14 Elm St. Licensed facility. Even after the death of its founder, this band is always worth hearing because it is so unique and has been left in the capable hands of its chief arranger/transcriber and longtime rhythm guitarist, Martin Loomer.

NOV 30, 8PM: Zula. Nick Fraser Trio: “Rock on Locke.” Nick Fraser, drums/composition; Tony Malaby, saxophones; Kris Davis, piano. Church of St. John the Evangelist, 320 Charlton Ave. W., Hamilton. zulapresents.org. $15 or PWYC. A concert by a very interesting trio featuring three of the most inventive players on the local scene, or any other for that matter.

NOV 30, 8PM: Zula. Nick Fraser Trio: “Rock on Locke.” Nick Fraser, drums/composition; Tony Malaby, saxophones; Kris Davis, piano. Church of St. John the Evangelist, 320 Charlton Ave. W., Hamilton. zulapresents.org. $15 or PWYC. A concert by a very interesting trio featuring three of the most inventive players on the local scene, or any other for that matter.

Toronto bassist Steve Wallace writes a blog called “Steve Wallace jazz, baseball, life and other ephemera” which can be accessed at wallacebass.com. Aside from the topics mentioned, he sometimes writes about movies and food.