Debargue and Geniušas Cool Hand Lukes

Born at the height of the Cold War in 1958, the International Tchaikovsky competition (held every four years, most recently in 2015) has a checkered history, beginning with its first winner, the American Van Cliburn. Conceived by the Soviet regime to celebrate the pre-eminence of its own musicians in a contest that welcomed contenders from around the world, Cliburn’s first-place finish (the jury included Shostakovich, Richter and Gilels) was acclaimed by music lovers in Moscow and the West. Last year’s competition likely produced the biggest surprise since 1958, although it wasn’t the winner, Dmitry Masleev, a by-the-book Russian.

Born at the height of the Cold War in 1958, the International Tchaikovsky competition (held every four years, most recently in 2015) has a checkered history, beginning with its first winner, the American Van Cliburn. Conceived by the Soviet regime to celebrate the pre-eminence of its own musicians in a contest that welcomed contenders from around the world, Cliburn’s first-place finish (the jury included Shostakovich, Richter and Gilels) was acclaimed by music lovers in Moscow and the West. Last year’s competition likely produced the biggest surprise since 1958, although it wasn’t the winner, Dmitry Masleev, a by-the-book Russian.

Lucas Debargue: The surprise was an unheralded Frenchman, Lucas Debargue, who swept through the first two rounds captivating audiences and critics with his playing. Seymour Bernstein (Seymour: An Introduction) was so moved, he sent an email to his list of followers celebrating Debargue’s artistry: “First, the Medtner is unbelievable! But I doubt that anyone will ever hear Ravel’s Gaspard performed like this. The French pianist Lucas Debargue must be in another world. Simply the most miraculous playing. Perhaps because of this alone he may win the competition.”

Reportedly, though, Debargue faltered in the final round concerto performances (he had limited experience in playing with an orchestra) and was awarded Fourth Prize. More importantly, the Moscow Music Critics Association bestowed their top honours on him, and SONY signed the 25-year-old pianist to a record contract.

And now Show One impresario, Svetlana Dvoretsky, has had the acumen to bring him to Toronto! In what promises to be one of the most exciting events of the season, Debargue and fellow Tchaikovsky winner, Lukas Geniušas, will give a unique, joint recital at Koerner Hall, April 30.

(Debargue’s first CD – which he chose to record live in Paris’ Salle Cortot to preserve a sense of risk and spontaneity – with works by Scarlatti, Chopin, Liszt, Ravel (Gaspard de la nuit), Grieg, Schubert and his own variation on a Scarlatti sonata has just been released. In a brief sampling, I was struck by the ethereal quality in his playing of Scarlatti’s K208/L238 Sonata and the breathtaking articulation of K24/L495. He made K132/L457 his own, ruminative, other-worldly. K141/L422 was Horowitz-like but with fresh emphases. He also found the melancholic quality of Grieg’s Melody from Lyric Pieces Book III and brought an exquisite elegance to Schubert’s familiar Moment Musical Op.94.)

If Debargue’s backstory weren’t true, few would believe it as fiction. He heard the slow movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No.21 K467 when he was ten, fell under its spell and into the world of music. He played a friend’s upright piano by ear before beginning lessons at 11 with his first teacher, Madame Meunier, in the northern French town of Compiègne. He credits her with helping him to find his way as an artist, but when he moved to Paris to study literature at Diderot University – yes, he learned English by reading Joyce’s Ulysses – he stopped playing piano (“I had no great guide, no one to share great music with,” he told the BBC), using the bass guitar as a musical outlet. After being away from the piano for years, he accepted an invitation to a competition in his home province. He won and began an intense pupil-teacher relationship with Rena Sherevskaya in Paris at 21.

In a recent interview Debargue gave the German magazine Crescendo right after he recorded his second solo album in Berlin, he was asked if he is living differently now, after the competition: “Externally everything’s changed but internally not. I’m looking for the clarity in my interpretation and I always feel that I need to progress. I’ve always had it that way. It is far more difficult for me to put up with many people around me than to concentrate on the music. Music gives me a new strength.”

Just a few days before his March 24 Paris recital, Debargue graciously took the time to answer a few of my questions via email. His answers were brief, to the point and illuminating:

What is your goal as an interpreter of music?

To find out and then keep as much as possible the spirit of the music I play. Let it live and reach the listener by being clear and expressive.

Which pianists from the past or the present do you especially admire? And why?

Horowitz: for his boldness and freedom. Sofronitsky: for his boldness and freedom. Gould: for his boldness and freedom. I strongly think that no other pianist reached the dimension of Rachmaninov’s playing though. Sokolov and Pletnev are my favorite living pianists. But how can one forget Art Tatum, Monk, Powell and Erroll Garner? Speaking strictly about piano playing they’re the best so far. [Debargue is also a jazzer who’s played clubs in Paris; his Ravinia Festival appearance in August will see him give one classical and one jazz recital on the same day.]

(I asked about two pieces on his Toronto program.) What is your approach to playing Gaspard de la nuit?

Live it from the inside after having found the right tempo and sound for each note.

And Scriabin’s Sonata No.4?

It’s music of fantasy and terror but one has to be very precise in choosing the right pictures and dynamics for each episode.

Lukas Geniušas: Coming from a musical family, headed by his grandmother, Vera Gornostaeva, a well-known Russian pedagogue, Lukas Geniušas took a more conventional path to his second-place Tchaikovsky finish, which followed second place in the 2010 Chopin Competition. Geniušas, like Debargue, is just 25 years old and also took time to answer my email questions. He told me that his grandmother’s importance in his musical life “both early and current is impossible to overrate.” It went beyond the bounds of music in building a foundation for the overall comprehension of art.

Geniušas told me that he has three goals as an interpreter of music: to create his own personal interpretations without harming the composer’s intentions; to seek moments of spiritual presence in a concert; and to pass on traditions that were passed on to him by his teachers.

He told me that he grew up admiring Richter and Michelangeli. “Somehow, intuitively, I have chosen them to be my favourites among many others whom I listened to on CD and DVD (yes, before YouTube!),” he said. “Their playing still appears to me the most complex, multi-layered and profound. Out of contemporary pianists, I would point to Radu Lupu, Zoltan Kocsis and Boris Berezovsky, who mostly capture my attention.”

When I asked him about his approach to Prokofiev’s Sonata No.7 and the seven Chopin mazurkas he will play in Toronto he told me that he first played Chopin mazurkas under his grandmother’s supervision when he was 11 or 12. He spoke of them as “little jewels” that were like a diary, about how a traditional Polish dance reveals “some of the most intimate shades of feelings” as embodied by Chopin, and how this music was a “particular side” of the teaching experience of his grandmother’s teacher, Henry [Heinrich] Neuhaus, who taught Richter, Gilels and Lupu, among many others from 1922 to 1964.

He called the Prokofiev Sonata No.7 one of the central pieces of 20th-century piano music: flawless in form, matchless in its violent brutality inspired by the outrage of WWII. Instead of taking a stormy virtuosic approach that may mislead the listener with flashy tricks, Geniušas prefers an articulated rendering that conveys its depth of meaning.

With eight CDs to his credit already, Geniušas’ path to an international career is well on its way. The Guardian wrote of his recent Southbank recital that he “plays with a prizewinner’s brilliance, yet with a mature ability to recreate a work’s architecture, and an expressiveness that doesn’t overtly draw attention to itself.” I can’t wait to hear him play the two-piano version of Ravel’s La valse with Debargue, the final piece of their Koerner Hall concert.

Geniušas has been in Toronto before: he came last December (and will return in April) to play for Dmitry Kanovich’s Looking at the Stars project that brings professional musicians to unusual venues. “This experience sweeps beyond words,” he said. “I never expected that performing in hospitals, shelters and jails could be so emotional and inspiring.”

Leonid Nediak: A student of Michael Berkovsky, Leonid Nediak (b. 2003) already has extensive concert experience. (He made his debut with the Montreal Symphony Orchestra under Kent Nagano in February 2014.) The grand prize winner of the 2013 and 2014 Canadian Music Competition, both times receiving the highest marks ever awarded in this event, Nediak makes his TSO debut next January playing Mozart’s Piano Concerto No.27 K595 under the baton of Peter Oundjian. At the recent announcement of the TSO’s 2016/17 season, Nediak played Rachmaninov’s Prelude in G Minor, a performance that touched all who were there. If you want to get a sense of this wunderkind before next January, there are two contrasting opportunities in the next few weeks. On Apr 16, Nediak joins with Norman Reintamm and the Cathedral Bluffs Symphony in Beethoven’s kinetic Piano Concerto No.3 Op.37. On May 7, he is the soloist in Rachmaninov’s romantic masterpiece, his Piano Concerto No.2 Op.18, with the Kindred Spirits Orchestra, conducted by Kristian Alexander, the second time Nediak has appeared with this Markham-based ensemble. (In 2014, they performed Chopin’s Piano Concerto No.1 Op.11 together.) In an email exchange, Alexander told me that Nediak played the first movement of the Rachmaninov concerto at a Kindred Spirits audition in 2014. “Leonid played very well, with the right balance of musicality, expression and technique. His performance was convincing and offered qualities that resonated with my interpretational concept about the piece,” he said, explaining the origin of the May 7 concert. Their Chopin collaboration came about just after that audition – Nediak already had it in his repertoire -- and “Leonid’s approach to Chopin’s melodic line was free-spirited and fresh and required a much higher level of elasticity and flexibility from the orchestra than usual.”

Describing Nediak’s qualities as a pianist, Alexander said: “Leonid is a great communicator, able to unlock the emotional content of the piece and unfold the storyline of the composition. He also has a reach and versatile palette of colours, natural sense of phrasing and flawless energy flow.”

QUICK PICKS

Royal Conservatory: Young organ virtuoso Cameron Carpenter brings his contemporary sensibility to Koerner Hall Apr 1. (Two days later, Apr 3, he moves his new custom-designed organ to the Isabel in Kingston, where, four days later, on A pr 7, the Korean-born Minsoo Sohn, will give a live version of his acclaimed recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations). Continuing with the Royal Conservatory, legendary pianist/conductor/teacher/mentor, Leon Fleisher, conducts the Royal Conservatory Orchestra, Apr 8. On Apr 12, the current crop of Rebanks Family Fellows performs a free concert (tickets required) in Mazzoleni Hall; on Apr 19, another free concert there is an opportunity to gauge the future as the Glenn Gould School presents its Chamber Music Competition Finals.

pr 7, the Korean-born Minsoo Sohn, will give a live version of his acclaimed recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations). Continuing with the Royal Conservatory, legendary pianist/conductor/teacher/mentor, Leon Fleisher, conducts the Royal Conservatory Orchestra, Apr 8. On Apr 12, the current crop of Rebanks Family Fellows performs a free concert (tickets required) in Mazzoleni Hall; on Apr 19, another free concert there is an opportunity to gauge the future as the Glenn Gould School presents its Chamber Music Competition Finals.

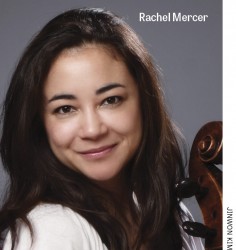

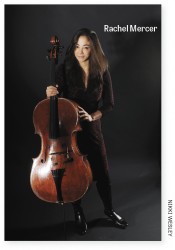

Syrinx presents Ensemble Made in Canada Apr 3 playing piano quartets by Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Omar Daniel at the Heliconian Club. The following week Ensemble Made in Canada travels to Kitchener-Waterloo Chamber Music Society for a double dose, Apr 8 and 9, including more Beethoven, Schumann and John Burge as well as the three pieces the group are doing in Toronto. The group’s cellist Rachel Mercer returns to KWCMS Apr 24 as part of Ménage á six, in a program of string trios by Dohnányi and Schubert along with Brahms’ Sextet No.1. And May 3 Till Fellner (whom I profiled in the March 2015 issue of The WholeNote) also returns to the Narvesons’ house in Waterloo – that “amazing place” – for a recital of works by Schumann, Berio and Beethoven.

The Cecilia String Quartet is joined by James Campbell at U of T’s Walter Hall for a performance of Brahms’ Clarinet Quintet, a cornerstone of the clarinet repertoire, Apr 4. Sunday, May 1 at 11am, the Cecilia invites children on the autism spectrum and their families to the next in its series of free Xenia Concerts. The one-hour performance, “Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms by the Numbers,” takes place in the Sony Centre’s lower lobby performance space.

The COC orchestra’s top two violinists, Marie Bérard and Aaron Schwebel, give a free noontime concert featuring music by Ysaÿe and Leclair, in the Richard Bradshaw Amphitheatre, Apr 5.

Music Toronto: Apr 5, Duo Turgeon, husband-and-wife duo pianists, perform a heavyweight program that includes a new arrangement of Ravel’s Second Suite from Daphnis and Chloe by Vyacheslav Gryaznov, Lutoslawski’s Variations on a Theme by Paganini and Brahms’ Variations on a Theme by Haydn. Music Toronto is well-known as the hub of string quartet concerts in this city, for bringing the world’s finest ensembles to the intimacy and congeniality of the Jane Mallett Theatre. On Apr 14, Music Toronto’s current season closes with the Berlin-based Artemis Quartet’s highly anticipated Toronto debut.

The TSO: Danish conductor Thomas Søndergård and Swiss pianist Francesco Piemontesi make their TSO debuts, Apr 6 and 8, with Sibelius’ cyclic, texturally rich Symphony No.1 Op.39 and Beethoven’s poetic Piano Concerto No.4 Op.58. Associates of the TSO present the Halcyon String Quartet (TSO principal and associate principal second violins, Paul Meyer and Wendy Rose, and TSO violist Kent Teeple and cellist Marie Gélinas) playing Schoenberg and Mendelssohn, Apr 11. Angela Hewitt remounts her Bach hobbyhorse to perform two keyboard concertos, BMV1052 and 1056 on Apr 13 and 14. (On Apr 16, only BMV1052 will be played.) Peter Oundjian accompanies Ms. Hewitt on all three days and leads the orchestra in Shostakovich’s Symphony No.8 Op.65, written in the shadow of the horror of WWII. The exciting composer/conductor Matthias Pintscher follows a performance of his own work, towards Osiris, with Mahler’s perpetually positive Symphony No.1 “The Titan” on Apr 28 and 30. Israeli pianist Inon Barnatan is the soloist in Mozart’s dark-hued Piano Concerto No.24 K491.

WMCT: The Women’s Musical Club of Toronto showcases the eminent violist Steven Dann, his family and friends, Joel Quarrington and Jamie Parker, in an eclectic recital dubbed “Dannthology,” on Apr 7. Their 118th season concludes on May 5 with a crowd-pleasing program by Honens Laureate, Pavel Kolesnikov.

The Blythwood Winds’ program on Apr 7 “explores the musical geography of continental Europe, contrasting old-school German romanticism with the French school of the early 20th century.”

In an intriguing concert at Alliance Française Toronto on Apr 8, Belgian pianist Olivier de Spiegeleir, plays works by Bach, Beethoven, Chopin and Schubert that the movies made even more famous.

In the third concert of a Beethoven String Quartet Cycle that concludes next season, Jeffery Concerts presents the Pacifica Quartet, quartet-in-residence at Indiana University, performing the master’s youthful Op.18 Nos.4 and 6 and the incomparable Op.59 No.1 (“Razumovsky”) on Apr 8.

Apr 9, one day after the Conservatory Orchestra’s concert, the U of T Symphony Orchestra (led by Uri Mayer) performs two masterpieces of the orchestral canon, Brahms’ Symphony No.3 and Shostakovich’s Symphony No.5.

Gallery 345 presents the indefatigable cellist, Rachel Mercer, in a solo concert, Apr 13. On Apr 15, the versatile violinist, Andréa Tyniec, joins forces with the sensitive collaborative pianist, Todd Yaniw, in a wide-ranging program of works by Sokolović, Ysaÿe, Piazzolla, Franck and Brahms.

The dynamic Eric Paetkau leads the Hamilton Philharmonic in Elgar’s ineffable Serenade for Strings and Tchaikovsky’s eternal Symphony No.4 on Apr 16.

Mooredale Concerts presents the infectious Afiara String Quartet in works by Haydn, Mendelssohn and Dvořák (where they will be joined by the redoubtable bassist Joel Quarrington) on Apr 17.

Finally, don’t let this under-the-radar concert presented by Music at St. Andrew’s/Austrian Embassy/Austrian Cultural Forum slip by. Austrian cellist, Friedrich Kleinhapl, and German pianist, Andreas Woyke, bring their romantic European sensibility to Mendelssohn, Franck, Beethoven, Piazzolla and Gade, Apr 22. Steve Smith wrote this about their September 2009 NYC recital: “Mr. Kleinhapl and Mr. Woyke supported their idiosyncratic vision of Beethoven with unimpeachable virtuosity and a thrilling unanimity of spirit. The intensity with which they listened and responded to each other’s impetuous gestures was its own reward, but they also shed new light on these familiar pieces.”

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.