“Grimaud doesn’t sound like most pianists. She is a rubato artist, a reinventor of phrasings, a taker of chances.”

— D.T. Max, The New Yorker, 2011

The remarkable French-born pianist Hélène Grimaud last visited Toronto a year ago when she performed Brahms’ Piano Concerto No.1 with the TSO and showed off her great dynamic range. Her intimate pianism exposed the intrinsic beauty of the slow movement and she entered fully into the passion of the third movement with its rhapsodic cadenza, spurring the audience into an immediate standing ovation. The year before she held the Koerner Hall audience in her sway with a performance of her Resonances CD that moved from Mozart to Berg to Liszt to Bartók, all united by the historical fact of the composers being children of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The remarkable French-born pianist Hélène Grimaud last visited Toronto a year ago when she performed Brahms’ Piano Concerto No.1 with the TSO and showed off her great dynamic range. Her intimate pianism exposed the intrinsic beauty of the slow movement and she entered fully into the passion of the third movement with its rhapsodic cadenza, spurring the audience into an immediate standing ovation. The year before she held the Koerner Hall audience in her sway with a performance of her Resonances CD that moved from Mozart to Berg to Liszt to Bartók, all united by the historical fact of the composers being children of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Her upcoming Koerner Hall appearance April 19 is typical of her adventurous spirit and imaginative programming. All the pieces are united by the theme of water: Berio’s Wasserklavier III; Takemitsu’s Rain Tree Sketch II; Fauré’s Barcarolle No.5 in F-sharp Minor, Op.66; Ravel’s Jeux d’eau; Albéniz’s Almería from Iberia Suite Book 2; Liszt’s Les jeux d’eaux à la Villa d’Este from Années de pèlerinage: Troisième année, Janáček’s In the Mists I; Debussy’s La Cathédrale engloutie from Préludes, Book I; concluding with Brahms’ Piano Sonata No.2 in F-sharp Minor, Op.2.

She told William Grimes of The New York Times: “Water is the element most necessary to life, the most precious resource for our planet, the most endangered and the one that poses the greatest risk on its potential for conflict.” Explaining her process in a video for the artnet News website, she described how she spent two years “boiling down” her conception of pieces having to do with water, to reduce it to “something very pure and abstract in its expression.” There were several Liszt works that fit her original idea but the one she finally selected was the “most abstract of all his water pieces.”

“An art form has to live in the moment,” she said. “It has to sound as if it is being written while you hear it.” On the San Francisco Classical Voice website she explained to Lara Downes earlier this year that the water program is “more fragile and vulnerable repertoire, and as an audience member you have to be willing to make that journey.”

When she performed the same pieces last December in New York over ten nights, she did so in an inch of water, mixing performance art metaphors. Anthony Tommasini in The New York Times described the riveting 20-minute process of filling the 55,000 square foot Drill Hall of the Park Avenue Armory with that inch of water for “Tears Become ... Streams Become ... ” He called the collaboration between Grimaud and the artist Douglas Gordon a “compelling, boldly original work, a dramatic combination of art installation, light show and piano recital.”

Brian Levine, the executive director of the Glenn Gould Foundation, sees in Grimaud a resemblance to Gould: “She has this willingness to take a piece of music apart and free herself from the general body of practice that has grown up around it.”

Ten days after her Toronto concert she performs with the Stamford Symphony Orchestra to bring awareness to her other passion: environmental education centred around wolves – she founded the Wolf Conservation Center in South Salem, New York in 1996.

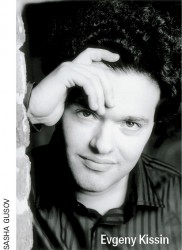

Evgeny Kissin: Evgeny Kissin’s mother was a piano teacher, his father an engineer. When Kissin was born (in Moscow in 1971), his sister, who was more than ten years older, was learning the piano. In Christopher Nupen’s DVD Evgeny Kissin: The Gift of Music, Kissin tells a tale one would be inclined to dismiss as apocryphal were it not for everything that has happened to him since. He had been a quiet baby, even standing on his cot in silence as his sister practised. When he was 11 months old, he opened his mouth and sang the Bach fugue she had just been playing (the Prelude and Fugue in A-Major from the 2nd book of the Well-Tempered Clavier). By the time he could reach the keyboard he was two and on his way to superstardom.

Evgeny Kissin: Evgeny Kissin’s mother was a piano teacher, his father an engineer. When Kissin was born (in Moscow in 1971), his sister, who was more than ten years older, was learning the piano. In Christopher Nupen’s DVD Evgeny Kissin: The Gift of Music, Kissin tells a tale one would be inclined to dismiss as apocryphal were it not for everything that has happened to him since. He had been a quiet baby, even standing on his cot in silence as his sister practised. When he was 11 months old, he opened his mouth and sang the Bach fugue she had just been playing (the Prelude and Fugue in A-Major from the 2nd book of the Well-Tempered Clavier). By the time he could reach the keyboard he was two and on his way to superstardom.

He elaborated in an interview with Frederic Gaussin for piano mag on iplaythepiano.com. “Before I began my studies at the School, I had been listening to music non-stop, practically from the day I was born. I became familiar very early on with all different kinds of music and pieces, until one day I became physically able to touch the keyboard and play this repertoire, these melodies, by ear ... From the very beginning, my taste was vast, very eclectic.”

In that interview he speaks of Chopin as the composer that he plays the most, “whose music is closest to my heart.” He continues: “From a pianistic point of view, Chopin was a revolutionary, the only one (with the exception of young Scriabin, who drew much from Chopin) who demands such flexibility from the hand at the piano.” Gaussin raises the topic of Debussy – not in Kissin’s repertoire – as someone who was not “any less sensitive or technically innovative than Chopin in his personal idiom.” Kissin responds that the same is true of Shostakovich, Schoenberg and Prokofiev, adding Messiaen, “whose works I do not yet play. His music is profound, very spiritual. He’s a perfect counter-example ... I see him in a way as the last survivor of an extinct species. I will certainly play Messiaen in the future.”

May 1 marks Kissin’s first solo recital at RTH in 15 years; his most recent appearance with the TSO was in May of 2012. It’s a virtuoso program beginning with Beethoven’s Sonata No.21 in C major, Op.53 “Waldstein” with its glorious third movement, followed by Prokofiev’s quietly charming, utterly logical Sonata No. 4 in C minor, Op.29. Then three nocturnes and six mazurkas by Chopin lead into Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 15 S.244/15 “Rákóczi March,” a quixotic foot stomper.

Kissin’s popularity is immense, his intellectual and musical gifts even more so. He once said that the main purpose of music is “that it elevates us into the world of the sublime.” The evening should be memorable.

Sara Constant:The WholeNote’s social media editor, flutist Sara Constant, headlines a concert titled “Xi” at Array Space April 24 featuring an intriguing line-up of mid to late 20th-century music. Stockhausen’s Xi (1987) for solo flute utilizes microtonal glissandi throughout. Denisov’s Sonata for Flute and Piano (1960) has been described as a collage of styles. Chiel Meijering, the composer of I Hate Mozart (1979) for flute, alto saxophone, harp and violin, says that he considers eroticism, sensuality and even obscenity prerequisites for a high-quality performance of his music. In each of Lutosławski’s Three Fragments (1953) the flute takes the melodic lead and the harp supplies a consistent, animated backdrop. Tsuneya Tanabe’s Recollections of the Inland Sea (1995) for flute and marimba was inspired by the scenic impression the composer had as an adult of a beautiful inland sea, Setonaikai, in the middle of Japan. The music, he says is his effort to “express my interior vision of the sea, spreading out before me….”

Seen and Heard:The elegant Vadim Repin shone in his Russian repertoire – Stravinsky and Tchaikovsky – in Koerner Hall March 6; The Vienna Piano Trio displayed an exemplary sense of ensemble and an unusually close seating arrangement in their well-received recital March 8 highlighted by Beethoven’s Kakadu Variations and two Mendelssohn Andantes (from his Trio Nos.1 and 2; the latter played as an encore); Till Fellner brought exceptional musicianship to Mozart’s Piano Sonata K282 on March 10. Kudos to Music Toronto’s Jennifer Taylor for bringing us Fellner as well as the London-based Elias Quartet March 19. French sisters Sara and Marie Bittloch on violin and cello set the tone for the quartet’s intimate sound and its impeccable sense of ensemble. Equally attentive were second violinist Scotsman Donald Grant and Swedish violist Martin Saving. Together the foursome brought heavenly pianissimos and wonderful silences that allowed Mozart’s music to breathe in his “Dissonance” Quartet K465 and unrelenting anger and passion to Mendelssohn’s last string quartet without losing the ruminative lyricism of its slow movement.

Quick Picks:

April 8 and 9 former TSO music director Jukka-Pekka Saraste returns to conduct Mahler’s glorious Symphony No.5 and accompany pianist Valentina Lisitsa in Rachmaninoff’s romantic masterpiece, his Concerto No.2. Conductor Peter Oundjian, soprano Isabel Bayrakdarian, violinist Sergey Khachatryan and pianist Serouj Kradjian join with the TSO April 22 for a concert celebrating Armenian music. It includes a double dose of Aram Khachaturian as well as the world premiere of Mychael Danna’s Ararat, a suite Danna constructed from his soundtrack to Atom Egoyan’s film of the same name. May 6 finds Oundjian supporting the up-and-coming twentysomething German violinist Augustin Hadelich in Mendelssohn’s justly celebrated Violin Concerto, a work which will appear on his next CD later this spring.

April 8 the co-artistic directors of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, cellist David Finckel (ex-Emerson Quartet) and pianist Wu Han, are joined by the versatile violinist Daniel Hope and violist Paul Neubauer in a compelling program of piano quartets by Mahler [Movement in A Minor], Schumann [E-Flat Major Op.47] and Brahms [No.1 in G Minor Op.25] at Koerner Hall. Also at Koerner Hall, April 24, take advantage of a rare chance to hear international superstar Yannick Nézet-Séguin conduct his hometown ensemble, Orchestre Métropolitain in a program of English music: Vaughan Williams’ Symphony No.4; Elgar’s indelible Enigma Variations and his ever-popular Cello Concerto with 20-year-old cellist Stéphane Tétreault as soloist.

April 10 the Mercer-Oh Trio play Haydn, Jean Lesage and Smetana under the auspices of the Kitchener-Waterloo Chamber Music Society. Pianist Eric Himy shows off his technical prowess in a program of Rachmaninov, Scriabin, Chopin, Albéniz and de Falla April 25. Still in Waterloo, TSO violinist Arkady Yanivker leads the Toronto Serenade String Quartet in music from Latin America April 28 while on May 2 it’s Sofya Gulyak of London’s Royal College of Music who tests the mettle of the Music Room’s piano in music by Liszt, Coulthard and Mussorgsky. She repeats the program in Toronto May 3 under Syrinx’s banner at the Heliconian Hall.

April 12 Syrinx presents the Seiler Trio (violinist Mayumi Seiler, cellist Rachel Mercer and pianist Angela Park) playing Beethoven’s beloved Archduke Trio, Mendelssohn’s Trio No.2 and Kevin Lau’s Trio.

April 12 Syrinx presents the Seiler Trio (violinist Mayumi Seiler, cellist Rachel Mercer and pianist Angela Park) playing Beethoven’s beloved Archduke Trio, Mendelssohn’s Trio No.2 and Kevin Lau’s Trio.

April 13 finds the Associates of the Toronto Symphony saluting the double bass with music of Rossini, Boccherini and Dvořák. Double bassist Tim Dawson teams up with violinists Etsuko Kimura and Angelique Toews. violist Christopher Redfield and cellist Marie Gelinas at Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre.

April 16 Music Toronto presents the Lafayette Quartet, an all-female ensemble who have remained together since their founding in 1986, a distinct rarity. Since then they have spent their time entertaining audiences and teaching some of Canada’s finest young string players from their base at the University of Victoria. Their program includes a middle Haydn quartet (No.28, Op.29, No.6), a late Beethoven (No. 15, Op.132) and Jean Coulthard’s String Quartet No.2, “Threnody.” The latter two pieces will be part of their Chamber Music Hamilton concert April 19.

April 17, group of 27: TSO principal oboist Sarah Jeffrey brings her warm sound to Mozart’s tuneful Oboe Concerto K314; Symphonies by C.P.E. Bach (the wild and beautiful Wq.179) and Haydn (No. 19), along with Jocelyn Morlock’s addictive Disquiet complete an intriguing group of 27 program. The group’s founder and music director, the dynamic Eric Paetkau, whom I interviewed in the December/January issue of The WholeNote, has just been named music director of the Saskatoon Symphony Orchestra. The night before the concert, April 16, The WholeNote will be hosting an open rehearsal of the group at the Centre for Social Innovation, 730 Bathurst St., ground floor. Doors open at 7:30pm. Experience g27’s lively playing in a casual, intimate atmosphere.

April 17, group of 27: TSO principal oboist Sarah Jeffrey brings her warm sound to Mozart’s tuneful Oboe Concerto K314; Symphonies by C.P.E. Bach (the wild and beautiful Wq.179) and Haydn (No. 19), along with Jocelyn Morlock’s addictive Disquiet complete an intriguing group of 27 program. The group’s founder and music director, the dynamic Eric Paetkau, whom I interviewed in the December/January issue of The WholeNote, has just been named music director of the Saskatoon Symphony Orchestra. The night before the concert, April 16, The WholeNote will be hosting an open rehearsal of the group at the Centre for Social Innovation, 730 Bathurst St., ground floor. Doors open at 7:30pm. Experience g27’s lively playing in a casual, intimate atmosphere.

April 25 Karin Kei Nagano, the teenage daughter of conductor Kent Nagano and pianist Mari Kodama (read the glowing review of her recording of all 32 Beethoven sonatas elsewhere in this issue), joins her mother for what should be a memorable afternoon of piano music; part of the BravoNiagara! Festival of the Arts.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.