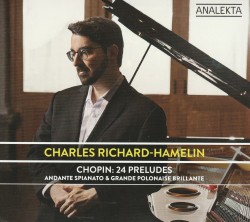

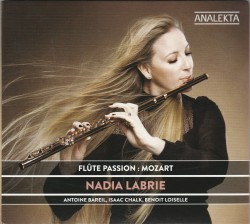

Flute Passion: Mozart - Nadia Labrie; Antoine Bareil; Isaac Chalk; Benoit Loiselle

Flute Passion: Mozart

Flute Passion: Mozart

Nadia Labrie; Antoine Bareil; Isaac Chalk; Benoit Loiselle

Analekta AN 2 8925 (analekta.com/en)

Mozart’s dislike of the flute has long been a topic of controversy, and whatever truth there may be behind the theory, some of his most charming works were written for the instrument, albeit the result of commissions received between 1778 and 1787. Five of these compositions – the Quartets K285, 285a and 285b in addition to the Quartet K298 and the renowned Andante K315 (as arranged and adapted by François Vallières) are presented here on this delightful Analekta recording performed by flutist Nadia Labrie and her accomplished colleagues Antoine Bareil, violin, Isaac Chalk, viola and Benoit Loiselle, cello. First-prize winner from the Conservatoire de musique du Québec, Labrie holds a master’s degree from the Université de Montréal and has appeared as soloist with such ensembles as the Orchestre Symphonique de Québec and the Vienna Chamber Orchestra. This is her third in the Flute Passion series.

These one-, two-, or three-movement works – never more than 17 minutes in length – may have only been written for the purpose of financial gain, but after 250 years they remain miniature gems – amiable chamber music where all parts are deemed equal.

As a cohesive ensemble, this group of four succeeds admirably! From the beginning, the listener is struck with the wonderfully intimate sound these musicians produce. Labrie’s pure and sonorous tone is perfectly complemented by the underlying strings that provide a sensitive partnership. This is nowhere more evident than in the second movement of K285b, a theme and six variations. Here, the artists approach the graceful intertwined melodies with great finesse, achieving a delicate balance throughout.

Félicitations à tous! This is a wonderful performance of engaging music played by four gifted musicians. Whatever feelings Mozart may have had for the flute, he would surely have approved!