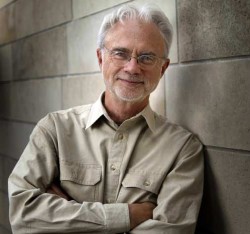

Remembering Johnny Cowell

It is with deep sadness that I have to report on the loss of another giant from our musical world. On January 22, just 11 days after his 92nd birthday, we lost Johnny Cowell, one of Canada’s most outstanding trumpet soloists. Rather than write some form of formal obituary, I would prefer to just recall a few situations over the years where our paths crossed. As is so often the case in the world of music, I cannot state with any certainty when or where I first heard the name Johnny Cowell or when I first met him. As I have mentioned in previous columns, there was a time when band tattoos were a significant part of summer festivities in many towns in southwestern Ontario. I know that his first band experience was with the Tillsonburg Citizens’ Band. At that time, I was a regular member of the Kiwanis Boys’ Band in Windsor. In a conversation with Johnny a few years ago I learned that we had both played in many of same tattoos. I know that he had played trumpet solos in some of these events. I may well have heard his solos then. However, the only young star trumpet player from those days that I remember was Ellis McClintock, later with the Toronto Symphony for many years.

Fast forward 20 or more years, and there I was playing in the same band as Johnny, with Ellis as the leader. It was a band, now long forgotten, for the Toronto Argonaut football club. Yes, even though the Argonaut head office appears to have no record of this band, from 1957 to 1967 the Argos had a 48-piece professional marching band which performed fancy routines on the field at all home games. Why would musicians of Johnny’s stature play in a football club band. Well, if you like football, why not get well paid union fees to watch a game? Since I was playing trombone in the front row and Johnny was playing trumpet in the back, we certainly had no contact with each other during rehearsals or performances. However, that is where we first met.

Fast forward 20 or more years, and there I was playing in the same band as Johnny, with Ellis as the leader. It was a band, now long forgotten, for the Toronto Argonaut football club. Yes, even though the Argonaut head office appears to have no record of this band, from 1957 to 1967 the Argos had a 48-piece professional marching band which performed fancy routines on the field at all home games. Why would musicians of Johnny’s stature play in a football club band. Well, if you like football, why not get well paid union fees to watch a game? Since I was playing trombone in the front row and Johnny was playing trumpet in the back, we certainly had no contact with each other during rehearsals or performances. However, that is where we first met.

During the times between rehearsals and performances there were usually small groups chatting. Frequently, the topic would turn to Johnny’s many compositions, particularly those on the hit parade. His 1956 ballad Walk Hand in Hand, which was just one of his many hits, could be heard on every radio station in those days. Actually, it was reported that at one time Johnny had more numbers on the US hit list than any other writer of popular music. However, his writing wasn’t limited to that genre. He was equally at home writing for trumpet and brass ensembles. I frequently play selections from the Johnny Cowell CDs in my collection. I am amazed at the gamut his trumpet works run. At one end of the spectrum there is his dazzling Roller Coaster and on the other end, his Concerto in E Minor for Trumpet and Symphony Orchestra.

My contact with Johnny was limited over the years, but there are a few meetings that come back to me regularly. Shortly after I began writing this column, I arranged to meet Johnny to get an update on his musical activities. Our meeting was anything but formal. It wasn’t at his home or at The WholeNote office. It was on a park bench in the town of Stouffville, not far from my home and close to the home of a family member of his. A few years after that it was a chance meeting during a break in one of the Hannaford Silver Band’s weekend events. Along with Jack Long of Long & McQuade, we discussed a somewhat less-than-serious subject, i.e. whether or not the names that we were using were the names on our birth certificates. The name “Johnny” was, in fact, the name on his birth certificate. For the other two of us, “Jack” was not our given name.

Then there was the time two years ago when I had the privilege of attending Johnny’s 90th birthday party. During that event, for a short while, I was flanked by two great figures in the Canadian music scene, Johnny and Eddie Graf. Now we have lost them both. At times one wonders how things might have been if Johnny had not turned down attractive offers which might have brought him fame by writing for stage productions or getting involved in the Nashville scene. While the trumpet was his all-abiding first musical love, that for his wife Joan and their family always had precedence.

By the time this issue is released, the Encore Symphonic Concert Band will be presenting a “Tribute to Johnny Cowell” in their regular noon hour concert, playing many of Johnny’s arrangements, on Thursday March 1. I’m sure that similar tributes will be presented by many other bands in the area over the coming months. Tell me about them and I’ll pass the word along.

A public memorial/celebration of life for Johnny will be held on Monday, March 12 at 7:30pm. It will take place at Scarborough Bluffs United Church, 3739 Kingston Rd, near the intersection of Kingston Rd. and Scarborough Golf Club Rd.

Junior Bands

Speaking of junior bands, it has just come to our attention that the 2018 National Youth Band will be hosted this year in Montreal by the Quebec Band Association. The guest conductor will be Wendy McCallum from Brandon University. We understand that this will be taking place in May, but don’t yet have confirmation on precise dates or location. The Yamaha Guest Soloist, on clarinet, will be Simon Aldrich from McGill University.

Changes

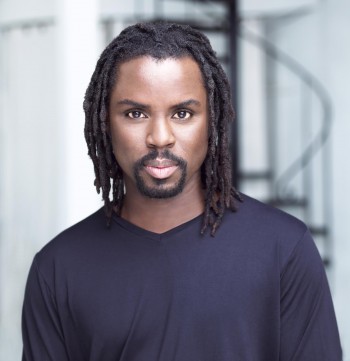

Over the years new bands spring up, old ones disappear and some undergo a significant transition. One group undergoing a major transition is the several New Horizons Bands in the Toronto area. Since their beginning close to ten years ago, the man at the helm has been Dan Kapp. However, not only is Dan relinquishing his leadership on the Toronto New Horizons scene, he is moving to Wolfville, Nova Scotia, soon after his wife Lisa retires from her teaching post this coming June. Rather than have a single person at the helm, now with quite a number of New Horizons bands in the Toronto area, there is scheduled to be a governing committee made up from the membership of the various NH bands. I hope to have more details on New Horizons activities soon.

It is always refreshing to learn of new groups arising from scratch. We just learned of a new swing band which is starting to make its mark. A frequent dilemma is how to give a new band a distinct name for people to associate with them. So, last summer a group forming up in Aurora decided that they should have a name that was unique, but easily recognized as having an affiliation with the name Aurora. Their name: the Borealis Big Band. The band is under the musical direction of Gord Shephard, a longtime resident of Aurora. He is the music director of the Aurora Community Band, as well as an instructor and conductor at York University where he is a PhD Candidate studying community music.

I was invited to attend one of this band’s rehearsals on January 31 and was almost blown away by a group that had just had its first rehearsal in September 2017. I heard a real powerhouse with a repertoire unlike that of any group that I have known. I asked a couple of members to describe this, and I received a variety of answers. The answer from Shephard was: “The Borealis Big Band was set up to provide an opportunity for members to play a wide variety of big band jazz styles including swing, funk, smooth and Latin/Cuban, and to play it to the highest quality possible with lots of room for improvisation for all interested members.” Unlike most such groups, when the band was formed they had designated leaders for each section. Their Debut Concert” went amazingly well. In the words of bassist Carl Finkle: “It was so much fun playing to a sold-out house for our first ever gig.” Their next scheduled performance will be on Friday June 22 at 8pm at the Old Town Hall, Newmarket, 460 Botsford St. We’ll have more on that in a later column.

Coming

On Sunday, March 4 at 3:30pm, the Wychwood Clarinet Choir will present their “Midwinter Sweets” program featuring an assortment of selections arranged by Roy Greaves, Alan Witkin, Richard Moore, Maarten Jense and Frank J. Halferty. Featured will be Five Bagatelles, Op.23 by Gerald Finzi, with artistic director Michele Jacot as clarinet soloist. Steve MacDonald, as tenor saxophone soloist, will perform Hoagy Carmichael’s Georgia on my Mind. Also on the program will be Minuet from “A Downland Suite” by John Ireland, Rikudim, Four Israeli Folk Dances by Jan Van der Roost and Henry Mancini’s Baby Elephant Walk. This concert will be held at The Church of Saint Michael and all Angels, 611 St. Clair Ave. W.

While it is a bit in the future, we might as well look ahead a bit to spring. The Clarington Concert Band’s annual spring concert will take place at 7:30pm on Saturday April 21 at Hope Fellowship Church in Courtice. As always, the program has something for everyone, with music from the band Chicago, to jazz and Broadway standards sung by their popular vocalist, Liza Heitzner. Clarinetist Katherine Carleton will perform Gordon Jenkins’ Blue Prelude and alto saxophonist Liz Jamischek will pay tribute to longtime Ellington soloist Johnny Hodges, with her rendition of Harlem Nocturne. The band’s regular conductor will be away and the band will be under the direction of Shawn Hills. Now retired after decades of heading the music program at Bowmanville High School, she is excited to direct her inaugural post-retirement concert with the Clarington Concert Band.

Jack MacQuarrie plays several brass instruments and has performed in many community ensembles. He can be contacted at bandstand@thewholenote.com.