Electric Bonds of Life: The Ins and Outs of Indie

Christopher Hoile, our regular opera columnist, will return to his usual spot here in March, so I will leave it to him in his upcoming column, next issue, to walk you through the fine points of the Canadian Opera Company’s just-announced 2018/2019 season.

Instead, as an enthusiastic but inexpert guest columnist, I thought it might be fun to start out by addressing myself not to the column’s usual readers, but to those of you who, either as guests to our city, or new readers of this magazine, or opera newbies might benefit from some friendly advice on how to traverse the potentially tricky terrain (both geographic and semantic) of opera in our fair town. The rest of you, who know your way around both these things, can skip ahead a few paragraphs, for what’s actually on the menu.

Rule One (Geography): Be careful what you ask for – especially if you are in a cab. You might be lucky (or unlucky) enough to get a cab driver who actually knows his way around town, in which case responding to “Where to?” with a nonchalant“The Opera House, please” could result in finding yourself 3.7km due east of your intended destination, in an old Queen St. E. venue (that is actually called The Opera House!) in a throng of 1,200 or so mostly bobbing and weaving concertgoers, listening to Avatar, The Brains & Hellzapoppin’, with Gilda and Rigoletto nowhere in sight.

The actual opera house here is called the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts (named after Vivaldi’s favourite hotel chain), and the city’s premier opera company, with typical Toronto understatement, is called the Canadian Opera Company. The COC shares the FSCPA, for performing purposes with Toronto’s premier ballet company, the equally modestly named National Ballet of Canada, otherwise known as NBoC, or “the Ballet.”

Rule Two (Semantics): Having established that “The Opera House” is not the opera house, let’s move on to an equally crucial distinction, this time semantics. It is this: in Toronto, expressing an interest in "the opera" does not mean the same thing as expressing an interest in "opera." The former is generally assumed by listeners to mean performances by the the city’s premier opera company in the city’s premier opera house. The latter can mean a far more nuanced range of things.

Rule Two (Semantics): Having established that “The Opera House” is not the opera house, let’s move on to an equally crucial distinction, this time semantics. It is this: in Toronto, expressing an interest in "the opera" does not mean the same thing as expressing an interest in "opera." The former is generally assumed by listeners to mean performances by the the city’s premier opera company in the city’s premier opera house. The latter can mean a far more nuanced range of things.

So listen very carefully when someone tells you about their relationship to this particular art form! The distinction between “I went to the opera” and “I went to an opera” is as important as the difference between a residential address on the 200s block of Chaplin Crescent or on the 300s block, the latter being where, after that winding avenue of stately homes crosses Eglinton Avenue, it peters out in a little thicket of mostly post-World War II midrise apartment buildings.

(I also suspect, with only the slightest tinge of arts worker bitterness, that more residents of the 200 block of Chaplin Crescent would be likely to have tickets to the opera than their trans-Eglintonian 300-block counterparts.)

All that being said, within their respective genres the COC and NBoC are, without doubt, the definite article, towering like forest giants above the Torontonian cultural undergrowth, and well-worth a visit.

So, now that we’ve established what the opera means in this town, and how to get there, let’s take a little ramble instead through the city’s operatic undergrowth, where the fascinating biodiversity of the town’s actual operatic culture can be observed and measured.

Welcome to the Undergrowth: It must first be said that “forest giant” and “undergrowth” are highly unscientific terms. For one thing, calling everything other than the two or three tallest trees in town the undergrowth is a vast oversimplification. Passionate devotees of Opera Atelier are almost as likely to say “the opera” as to say “an opera” when asked where they have been. And there are other companies out there (Tapestry and Against the Grain) which at this point have the capacity to flip between mainstream finesse and indie panache almost at will. There are also theatre companies that have tall tree status within their own non-operatic realm that occasionally turn their attention to the art form (Canadian Stage Company is perhaps the most notable among these, and we'll have much more to say about them in a future issue.)

That being said, there’s a pleasantly rich tangle of operatic activity in town. Some of it, to be sure, focuses on rendering, on a smaller, more community-friendly scale, the repertoire most usually performed at “the opera” (Toronto City Opera, Opera York and Opera by Request come most readily to mind.)

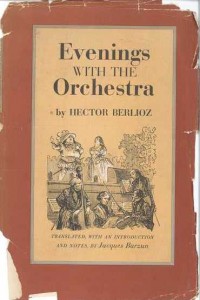

And there is a uniquely Torontonian gem of a company around, called VOICEBOX: Opera in Concert, featuring top-flight performers in very lightly staged concert renditions, occasionally of new works but more often of rarities from the grand operatic tradition too risky or problematic, for one reason or another, for the forest giants to stage.

And then there is the mysterious thing called “Indie Opera.”

Indie Opera: At any given moment in time, Toronto seems to have 10 or 12 indie opera companies, on the go. Not always the same 10 or 12, mind you. Birth, decay and death are as necessary to a fertile operatic climate as they are to a good operatic plot. And even within the 10-or-12-company official membership of Indie Opera Toronto, it doesn’t do to generalize as to individual companies’ stated purposes.

Loose Tea Music Theatre, for example, is currently investing significant time and passion in a third-Sunday-of-every-month residency at Bad Dog Comedy Theatre on Bloor near Ossington (their next show is February 18), with a madcap improvised show called “Whose Opera Is It Anyway?” Under the inspired co-direction of Loose Tea artistic director Alaina Viau and comedy improv heavyweight Carly Heffernan, Loose Tea’s core ensemble has been steeping themselves in the standard games and structures that are the meat and potatoes of comedy improv. It’s a win-win-win. The show is a delight for fans of opera and of improv alike. And the ensemble itself is learning the conspicuous bravery of actually listening affirmatively to each other and responding truthfully in the moment – attributes that will stand them in good stead as they re-engage down the line with projects with the social and artistic heft of their 2016 Carmen.

Meanwhile, Essential Opera, another indie stalwart, is working towards an April 22 concert performance with Orchestra Toronto of Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi, an exercise in cross-genre audience building and in carrying forward the key message inherent in the company name -- namely that the essence of opera is something different than its trappings and machinery.

What these two companies, and everything in between, have in common is that at some point in their gestation some individual or individuals said “If we are going to ever get to do operatically what we are interested in, we are going to have to do it ourselves.”

As already mentioned, you can get a rough idea of the players in the indie opera undergrowth by visiting indieoperatoronto.ca. But again, a cautionary note: like its member companies are, or were, Indie Opera Toronto has sprouted from do-it-yourself, volunteer-driven roots. So the information on the website is best viewed as a snapshot of the scene, compiled at a particular moment rather than chapter and verse. It nevertheless offers a way to delve deeper into projects and plans of the companies listed there, but it sometimes takes the site a while to catch up with the scene.

The Electric Bond Opera Ensemble

Soprano Sara Schabas' newly created Electric Bond Opera Ensemble is definitely the new kid on the indie opera block, but Schabas herself is not, having grown up in the world of “the opera.” So she comes to this project with a deeply rooted, organic passion for the storytelling power of the medium. Her grandfather, Ezra Schabas, among other musical achievements, was head of the University of Toronto Faculty of Music performance and opera department from 1968 to 1978, where Sara Schabas herself went on to complete an undergraduate degree in vocal performance. “Dad was a french horn player before he became a lawyer,” she explains, “and both my parents and all my grandparents had a huge love for opera. Starting at age four, they’d put on a VHS of La Boheme, Act 1 for me. I’d listen to Saturday Afternoon at the Opera every week. I was that weird kid who loved opera from a very young age. So it’s always been a very natural thing for me.”

The ensemble's name, she tells me, is a quote from Thomas Huxley, the agnostic 19th-century British biologist, nicknamed “Darwin’s Bulldog.” “We aim to present classical and operatic works that tell untold stories, reminding audiences and performers of what Huxley called the ‘electric bond of being’ by which all people are united.”

The ensemble's name, she tells me, is a quote from Thomas Huxley, the agnostic 19th-century British biologist, nicknamed “Darwin’s Bulldog.” “We aim to present classical and operatic works that tell untold stories, reminding audiences and performers of what Huxley called the ‘electric bond of being’ by which all people are united.”

The company’s first show dives headlong into the company's stated aims – a fully staged, Canadian premiere performance, on February 10 and 11, of “ two one-act operas of survival,” Another Sunrise and Farewell, Auschwitz, by U.S. composer Jake Heggie and librettist Gene Scheer – partners in operatic crime for Moby-Dick (2010) and the more recent It's a Wonderful Life which premiered at Houston Grand Opera in 2016.

The Toronto Another Sunrise and Farewell, Auschwitz will take place in Beth Tzedec Congregation’s Herman Hall on Bathurst Street and will represent, at several different levels, a journey of return for Schabas. We chatted briefly in The WholeNote offices.

WholeNote: So how did you discover Heggie?

Schabas: After undergrad at U of T, I went to Chicago College of Performing Arts at Roosevelt University for a master's, and from there into an internship with Dayton Opera Company. I was one of their artists-in-residence and Jake Heggie actually came and did a short residency with us – so we put on a concert of his works that he narrated and coached us on. And then we also did Dead Man Walking [Heggie’s first big hit, in 2000, with librettist Terrence McNally]. Getting to know him and hearing the personal stories behind each of his works really drew me in, as well as the visceral reaction we got from audiences in all those performances. So when I heard he had this Holocaust one-act/two-act opera I thought it would be a really interesting experience for me not only to perform more of his works but to explore my heritage through an art form that doesn’t often explore Jewish stories.”

So which was the chicken and which was the egg? You wanted to do this particular opera so you decided to do it yourself? Or you wanted to do your own thing, and this was a perfect fit?

Well, moving back from the States after my student visa expired it took a bit to re-establish myself within the community. So, like many other singers, I started producing my own concerts, and I did a lot of refugee fundraising recitals – three of them when I moved back – as well as some other volunteer work. I knew I wanted to produce my own work with this specific social-justice-oriented angle. This piece was already there as a side passion project, and it fit perfectly.

Right now I’m guessing you are in the DIY thick of things …

Exactly right. When you’re in do-it-yourself mode you’re doing your own press releases, you’re pulling together the partners and in the middle of all of it you’re learning the music and all the rest of it.

So who is the actual artistic team you've assembled? The ones who are going to force you to take off your producer’s hat when you’re on the stage? Who had you already worked with?

SS: Yeah – well Michael Shannon, our music director, I worked with earlier this year at Tapestry Opera for Bandits in the Valley. I played Henri, which was both a piano-playing and a singing character. So Michael Shannon and I got quite close because he had to help me a lot with the piano, which is not something I’ve studied extensively, and he was just such a vibrant strong leader in that experience and in the other performances that I’ve seen him in that I thought he would be a perfect person to take the helm on this project. And Aaron Willis I’ve actually never worked with before ...

Aaron is …?

He’s the director – I’ve worked with his wife, Julie Tepperman, who was the librettist for Bandits in the Valley so we did a lot of talking about our shared Jewish heritage and I initially actually reached out to her to see if she’d be interested in directing. She she said she wasn't, but her husband would be. He has never directed an opera by himself before – he assisted with Julie last year at Canadian Stage – but he’s a very interesting director: he’s done a lot of immersive theatre, some of which also has a Jewish angle. He has this one famous play called The Yehud which is a comedy about two Orthodox Jews and what happens right after they get married – there’s the yehud room. The opportunity for me taking on this really meaty acting role to work with someone – he also has a background as an actor – with a strong theatrical background was a priority. So some old, some new ...

You say it's a meaty role? Does that tie in with the “untold stories” goal you talked about?

Krystyna Zywulska is a very interesting story because she’s someone who actually hid her Jewish identity: when she was in the Warsaw ghetto she created this new identity, and when she was imprisoned at Auschwitz it wasn’t as a Jew it was as a political prisoner; her story is one of reconciling with the terrible thing she did to her fellow Jews, and then finding out if her past can exist with her present …

So how to embrace the dichotomy ...

Absolutely. So hers is a very conflicted Holocaust story and a very rich one.

And the partnership with Beth Tzedec and with the Azrieli Foundation. How does all that happen?

Well – since moving back I’ve been doing a lot of singing in synagogues, so I’ve been a member of the choir at Beth Tzedec and they’re very interested in presenting survivors’ testimonies in different ways so basically I pitched the opera to them and they were interested. Azrieli also happened to be interested ...

How did you know about Azrieli?

That was a bit of an aha moment: I was at the Canadian Children's Opera Company's Brundibár last year, for which I know they also received help from the Azrieli foundation. So then I started looking them up ...

So, getting back to the show itself, what’s the breakdown of instruments?

It’s piano, clarinet, violin, cello and bass.

Sounds like almost a klezmer feel to it.

Yeah, the clarinet voice definitely has that feel. It has this certain chant-like melody that occurs throughout the piece and I was just remarking to Michael Shannon on how Jewish it sounds at times.

So how did you find the other singers?

Again, recommendations – I sang with Sean Watson in the Beth Shalom choir and Georgia Burashko I’ve just heard wonderful things about and she was very interested.

Any other projects already in the works? Do you dare wait to get the next thing going?

Yeah ... there are some ideas floating out there ... my friend Jacques Arsenault who’s a tenor and accordion player – also from Bandits in the Valley – and a couple of other friends and I are working on a potential Satie program for next year but we’re still finding the social justice, untold-story lens for that. He was a bit of an outcast in his lifetime – Satie – and he also has a lot of interesting dichotomies in his life between his cabaret works and his more formal works so we’re looking to put together a program about that. That’s the main thing right now. But it’s true – once you do one you have to start thinking about the next

Even while you're still doing the one ...otherwise you're stuck in the middle ...

Yeah – and then you miss out.

David Perlman can be reached at publisher@thewholenote.com.