Virtuoso Violins Piano Prodigies

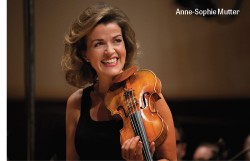

Anne-Sophie Mutter was only 22 years old when she started her first foundation in aid of young string players; it was limited to the area of Germany at the foot of the Black Forest where she was born. As a teenager if had become clear to her – she told me in a recent telephone conversation – that “we string players sooner or later run through the same circle of problems mainly to do with finding the right teacher but also with finding an instrument which can be a musical partner for life, and hopefully financially obtainable as well. So my first foundation was sort of a tryout, how I could help younger colleagues.”

Anne-Sophie Mutter was only 22 years old when she started her first foundation in aid of young string players; it was limited to the area of Germany at the foot of the Black Forest where she was born. As a teenager if had become clear to her – she told me in a recent telephone conversation – that “we string players sooner or later run through the same circle of problems mainly to do with finding the right teacher but also with finding an instrument which can be a musical partner for life, and hopefully financially obtainable as well. So my first foundation was sort of a tryout, how I could help younger colleagues.”

Now in its 16th or 17th year, the Circle of Friends of the Anne-Sophie Mutter Foundation provides instruments for the foundation’s chosen scholars as one attempt to help. Another is commissioning new works. The Toronto program of Anne-Sophie Mutter and the Mutter Virtuosi in Roy Thomson Hall on November 21 opens with a commission by the Circle of Friends for double bass -- Ringtones by the American Sebastian Currier.

“Obviously throughout history the double bass has been one of the important pillars of the orchestra but there have been very few solo performers,” she said. “Roman Patkoló was one of my first scholars and I was totally blown away by his talent, by his artistry and great passion,” she continued. So even though her original plan had not included the double bass that much, it became “really a main focus of my foundation” with four pieces commissioned for Patkoló starting with “a beautiful double concerto” written and recorded by André Previn, “a very pizzazz-y solo piece by Penderecki,” as well as “a very intellectual spherical piece” by Wolfgang Rihm.

“Ringtones is a very serious piece but also leaves room for fun,” she continued, explaining that it’s a way to build a case for the virtuosity of the bass. Showing off her sense of humour, she dead-panned: “Ringtones are for the very first time in a concert welcome!”

As to what it’s like to perform with her students and former students -- who comprise the Mutter Virtuosi with whom she’s sharing the RTH stage – she recounts how when she was 13, Karajan treated her as an adult, addressing her with the German equivalent of “vous,” not “tu,” which would be normal in speaking to a 13-year-old. She points this out to indicate that experience and age are irrelevant to the “all-embracing strength of musical language.”

“No matter how young we are,” she went on. “At the end of the day it’s really your personal viewpoint, and of course, a certain skillfulness, that we only have to share.

“Of course I’m looking with great love and devotion into the lives of the ones I’ve been a small part of for 10 or 15 years and it’s beautiful to see how all of them have found their place in music... it is really the Olympic ideal to make the best out of what you have that is the driving force behind the [foundation’s] selection process.”

Mendelssohn’s great Octet is on the program in Toronto, so I asked Ms. Mutter why she admires the composer so much. Her answer was especially revealing. She began by saying that it was only eight or ten years ago she re-started learning the Violin Concerto:

“My wonderful teacher Aida Stucki never seemed to be quite taken by what I did with the piece and I never felt quite free with what my vision was. So it wasn’t one of the pieces I felt comfortable with and when it was up to me to decide what repertoire I would delve into I thought, ‘Well if no one likes my Mendelssohn playing, I’ll just stop playing it.’

“Then many years ago, I think around Kurt Masur’s 75th or 80th birthday [80th in fact, in 2007] he said ‘I want a gift from you: Restudy the Mendelssohn and let’s do it together.’ Of course, when Kurt Masur wishes something I’ll go to the end of the world for him, so the least I could do was restudy the piece and come to different conclusions. And he gave me wonderful insights.

“I came to admire Mendelssohn as the humanist he was and actually today he’s for me a perfect example of what I expect a musician to be, also [what I expect] of the younger generation: someone who is socially engaged and open-minded and goes with open eyes through life.”

She explained that Mendelssohn built the first music school in Germany for “students of all cultural and financial backgrounds,” and of course, “he resurrected Johann Sebastian Bach.” She summed up her feelings: “Somehow I seem to admire an artist in general even more if he also turns out to be a useful member of human society, apart from being very skillful at what he’s doing.

“Obviously the Octet stands for all these qualities. There’s such a beautiful quote from Mendelssohn who used to say, particularly about the Octet, that when he is writing or making chamber music he hopes that it is ‘like a conversation between very well-educated and interesting friends.’

“And this is pretty much how I feel when I am playing with my young colleagues. We all bring our own viewpoints to it and there’s a lot of freshness and passion in the air, which is the main ingredient really of rediscovering what we think we know.”

“And this is pretty much how I feel when I am playing with my young colleagues. We all bring our own viewpoints to it and there’s a lot of freshness and passion in the air, which is the main ingredient really of rediscovering what we think we know.”

I had read that Ms. Mutter had recently begun using a baroque bow to perform Bach, so I asked her if she would be using one in the Toronto performance of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, only to discover that new regulations involving animal materials made it difficult to bring even copies to North America. She told me that she will continue to play Bach with it wherever she is able mainly “because the original phrasing in the Bach scores is only to be obtained by bows which are much lighter in the frog [the bottom part of the bow that is nearest to the hand] which was the case in Baroque times.”

While they don’t use baroque bows in their playing of the Vivaldi, it’s nevertheless much less dense and more transparent playing today than what she thought was proper in the 1980s. In Toronto she and her Virtuosi would be keeping that “transparent and very airy sound in mind, for sure.”

I was quite curious about what led Ms. Mutter to take up the violin as a child since I knew that she didn’t come from a family of musicians. She spoke of growing up “kind of a tomboy” with two older brothers in a house with a lot of classical music and literature. Her father was a journalist who later became a newspaper editor. As engagement presents her parents gave each other recordings by Furtwängler and by Menuhin. “That shows how much that was part of their life and how much that became part of our life at home.”

“We listened to a lot of classical music as well as jazz,” she continued. “And that is probably the reason for my deep-rooted love of jazz because I felt so comfortable and basically soaked it up like mother’s milk.

“So for my fifth birthday – it must have been the constant presence of that violin sound which made me want to try it for myself. And I’m still trying it,” she added, almost seriously.

I asked her about the violinists who made an impression on her in her youth and the depth of her answer was quite telling: “The great, unforgettable David Oistrakh definitely left the deepest impression: his presence on stage, the warmth of his personality. I remember there were students sitting literally at his feet ... Yes, I was six years old and he played the three Brahms sonatas.

“A few years later I was fortunate enough to hear Nathan Milstein who became another of my [favourites]; I obviously also played with Menuhin at a later stage of his life; I heard Isaac Stern in person; I was rather close to Henryk Szeryng. I was really very fortunate to hear all of these icons of violin playing at a still fabulous age and in great shape.”

As to what makes a great violinist great, Ms. Mutter responded that “we’re all trying to be a well-rounded musican.” She finds the idea of being a specialist rather boring, caught up with technical details and perfecting them without really having the scope to see the bigger picture. She thinks it’s wonderful that the violin is “an instrument which is best in company with someone else, with another musical partner.” At the same as she extols the virtues of “just being a useful part of the whole” she says, “Of course you have to find – as violinist, pianist or conductor – you have to find an angle where music is newly or freshly or whatever ... it has to bring a spark to something.”

She spoke of shattering the illusion of the listener who might think he knows what you’re playing already and may feel slightly tired of it. “Of course that illusion has to be taken away the moment that the particular artist goes on stage,” she explained. ”Then it really has to be totally fascinating.” When I enthusiastically agree, she responds, “Hopefully.”

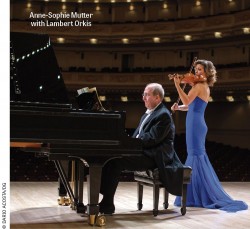

Her extensive discography which began when she was just 15 – Deutsche Grammophon celebrated her 35-year recording career with a 40-CD box set last year and her 25-year collaborative partnership with pianist Lambert Orkis was marked with The Silver Album, a 2-CD compilation this year – prompted a question about what, if anything in the violin repertoire she looks forward to recording.

“Sadly, sadly, of course life is too short,” she responded. She is fascinated, she went on to say, with the great encores that Jascha Heifetz used to play, “a repertoire that is sadly, frowned upon in German-speaking countries.” Listening to two CDs over the course of an evening recently, she remarked how struck she was by the “nobility of this great violinist,” and that for the next few months she would be exploring this repertoire. Beyond that? “The repertoire is endless – you can go in this direction or that, ...Walton, ... Barber, more contemporary music ... the Beethoven string quartets.”

“Yes, Paul, it’s kind of [a mock scream over the phone, as if saying it’s all too much to contemplate]” I counter that it’s something to look forward to; “One after the other,” she replies.

There is so much to do. Even as she takes the Mutter Virtuosi on their first North American tour, their New York appearance is just one part of Carnegie Hall’s Anne-Sophie Mutter Perspectives in which all facets of her musicianship will be on display, from her recent appearance in the Bruch Violin Concerto No.1 with the Berlin Philharmonic under Simon Rattle at the beginning of October, to the Annual Isaac Stern Memorial Concert November 11 (with Orkis on piano for Beethoven’s “Kreutzer” sonata, and a performance of Currier’s Ringtones with Patkoló), to a concert next spring with Yefim Bronfman and Lynn Harrell (including Beethoven’s “Archduke” trio). Playing Sibelius, Berg and Moret with the Danish National Symphony Orchestra and Michael Tilson Thomas’ New World Symphony completes the six-concert series.

WholeNote readers will be interested in the fact that the Mutter Virtuosi Carnegie Hall concert on November 18 will be live-streamed and available on medici.tv for view for 90 days thereafter. Like the concert in Toronto three days later, the program includes Vivaldi’s Four Seasons but instead of Mendelssohn and Currier the Carnegie program features Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins BWV 1043 and André Previn’s.

What does she think about the live streaming, I ask. “It’s not downloadable but you can look at it and get horrified from another angle,” she jests, before adding more seriously: “I feel very honoured [because very few concerts are being streamed].”

So anyone going to the November 21 Roy Thomson Hall concert (or contemplating it) will be able to get a sneak preview in the few days before, or more likely cement a memory of parts of the Toronto concert any time through mid-February.

Jan Lisiecki: Like Mutter, Calgary-born pianist Jan Lisiecki began music lessons at five and started recording for Deutsche Grammophon as a teenager (he was 17). He will bring his musical sensibilities to Beethoven’s third, fourth and fifth piano concertos in a series of concerts with the TSO November 12 to 22. I was fortunate several summers ago to hear Alfred Brendel play all five of the concertos with the Boston Symphony at Tanglewood and I can’t overstress what a pleasure such concentrated exposure can be. Guest conducting the TSO will be Thomas Dausgaard who has paired each concerto with a symphony by his Danish countryman, Carl Nielsen. Nielsen, a contemporary of Sibelius, is known for his energetic post-romanticism, and he was quite explicit about the life force music represented to him. Symphony No. 4 “The Inextinguishable” is particularly expressive in this vein, having been composed during the first half of the First World War. It’s paired with Beethoven’s most lyrical piano concerto, the Fourth, November 12 and 13.

Jan Lisiecki: Like Mutter, Calgary-born pianist Jan Lisiecki began music lessons at five and started recording for Deutsche Grammophon as a teenager (he was 17). He will bring his musical sensibilities to Beethoven’s third, fourth and fifth piano concertos in a series of concerts with the TSO November 12 to 22. I was fortunate several summers ago to hear Alfred Brendel play all five of the concertos with the Boston Symphony at Tanglewood and I can’t overstress what a pleasure such concentrated exposure can be. Guest conducting the TSO will be Thomas Dausgaard who has paired each concerto with a symphony by his Danish countryman, Carl Nielsen. Nielsen, a contemporary of Sibelius, is known for his energetic post-romanticism, and he was quite explicit about the life force music represented to him. Symphony No. 4 “The Inextinguishable” is particularly expressive in this vein, having been composed during the first half of the First World War. It’s paired with Beethoven’s most lyrical piano concerto, the Fourth, November 12 and 13.

Itzhak Perlman: Like Mutter, Izhak Perlman is a towering figure on the world violin stage and occupied as well with music education. His upcoming RTH recital December 1 with pianist Rohan De Silva crosses three centuries with music by Vivaldi, Schumann, Beethoven and Ravel. At his concert here two years ago with collaborator De Silva, he introduced the entire post-intermission part of the program from the stage, with the joyful aplomb of a Borscht Belt kibitzer. Any opportunity to hear what he cals his “fiddle playing” should not be missed.

Itzhak Perlman: Like Mutter, Izhak Perlman is a towering figure on the world violin stage and occupied as well with music education. His upcoming RTH recital December 1 with pianist Rohan De Silva crosses three centuries with music by Vivaldi, Schumann, Beethoven and Ravel. At his concert here two years ago with collaborator De Silva, he introduced the entire post-intermission part of the program from the stage, with the joyful aplomb of a Borscht Belt kibitzer. Any opportunity to hear what he cals his “fiddle playing” should not be missed.

Leon Fleisher: For many years this city has been fortunate to have Leon Fleisher in its midst. As the occupant of the inaugural Ihnatowycz Chair in Piano at the Royal Conservatory, his presence has been felt in teaching, conducting, performing, examining and giving masterclasses. On November 25 at the Bloor Hot Docs Cinema, he will appear on stage in a Q & A after the screening of the fully packed 17-minute film, Two Hands: The Leon Fleisher Story, which documents his battle to overcome focal dystonia, a movement disorder that affected the use of the fourth and fifth fingers of his right hand. Watching him rise from the depths of despair at the peak of his concert career to remake his life as a musician is thrilling to behold. Take advantage of the opportunity to meet him in person.

Three days later on November 28, Fleisher conducts the Royal Conservatory Orchestra in a program that includes Mozart’s Symphony No.39 and Brahms’ Symphony No.3. On the mornings and afternoons of November 29 and 30 he will give masterclasses in Mazzoleni Hall. He will share a musical legacy traceable back to Beethoven directly through his teacher Artur Schnabel and Schnabel’s teacher Theodor Leschetizky who studied with Carl Czerny who studied with Beethoven. Anton Kuerti can claim a similiar connection through another pupil of Leschetizky, Mieczysław Horszowski, who taught Kuerti.

Three days later on November 28, Fleisher conducts the Royal Conservatory Orchestra in a program that includes Mozart’s Symphony No.39 and Brahms’ Symphony No.3. On the mornings and afternoons of November 29 and 30 he will give masterclasses in Mazzoleni Hall. He will share a musical legacy traceable back to Beethoven directly through his teacher Artur Schnabel and Schnabel’s teacher Theodor Leschetizky who studied with Carl Czerny who studied with Beethoven. Anton Kuerti can claim a similiar connection through another pupil of Leschetizky, Mieczysław Horszowski, who taught Kuerti.

The evening at the Bloor also includes the feature-length, documentary Horowitz: The Last Romantic, a true curiosity by the noted filmmakers Albert and David Maysles (best know for Salesman, Grey Gardens and Gimme Shelter). The impish pianist and his shrewd wife Wanda (Toscanini’s daughter) are filmed in their apartment where Horowitz is recording an album at the age of 81. The up-close camerawork devoted to his fingers is just one of the attractions of this fascinating film.

Bavouzet and the LPO: Coincidentally, pianist Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, who recently played Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3 at RTH October 17 with an energetic London Philharmonic Orchestra under Vladimir Jurowski, suffered from functional dystonia that affected his right hand from 1989 to 1993. In the Prokofiev Bavouzet moved confidently from wistful calm to devilish passagework, from idiosyncratic note picking to mysterious pianissimos as he revealed the composer’s Russian soulfulness. In the evening’s other major work, Shostakovich’s Symphony No.8, the LPO displayed great clarity and airiness including wonderful sound clashes, vibrant searing melodies in the strings, terrific brass work and yeoman flute playing that set up the intermittently febrile march of the second movement and the sardonic third before the gratifying, sombre conclusion.

And So Much More: MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship-winner Jeremy Denk leads a parade of world-class pianists into November’s concert halls. He’s followed by the inimitable Richard Goode, the dynamic aestheticism of Simon Trpčeski, the elegance of Angela Hewitt (in a program that ranges far and wide from Bach and Scarlatti through Beethoven’s Op.110 to Albéniz and Liszt), to Mooredale Concerts’ “Piano Dialogue” between David Jalbert & Wonny Song and the adventuresome Christina Petrowska Quilico whose name is often found in the pages of TheWholeNote’s CD section.

And then there’s the Dover Quartet, the Daedalus String Quartet, the Cecilia String Quartet, the Windermere String Quartet, the Zuckerman Chamber Players, the Canadian Brass, Leonidas Kavakos & Yuja Wang, Dmitri Levkovich ... It goes on and on. Like Tchaikovsky, Danny Kaye’s famous tongue-twister of a patter song, name after name, concert after concert. What riches there are to be found in this issue’s listings.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote. He can be reached at editorial@thewholenote.com.