Something in the Air | Understanding Pianist Paul Bley’s Musical Legacy - November 2021

Although Paul Bley died in 2016 the extent of his legacy and associations are still being felt. That’s because the pianist was one of the few jazz players who moved through several musical areas and made his mark on each. Born in Montreal on November 10, 1932, he would have been 89 this year. A piano protégé, Bley began as a teenage swing pianist in his native city. Yet he became so proficient a bopper after his move to New York in the early 1950s that he was soon playing with Charles Mingus and Charlie Parker. An encounter with Ornette Coleman allowed him to bring freer ideas to his improvising and composing during the 1960s and he worked with members of the burgeoning free jazz movement during that decade and afterwards. Later on, while continuing to play contemporary jazz with various acoustic bands, he expanded his interests into early experiments with the Moog synthesizer and when he started his own record label he made sure that visual as well as audio tracks were created. He also taught part-time at the New England Conservatory (NEC) and over the years collaborated and recorded with a cross section of international musicians. Read a more detailed view of Bley’s life and career in the February 2016 issue of The WholeNote.

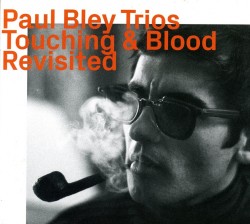

By the time Touching & Blood Revisited (ezz-thetics 1108 hathut.com) was recorded in 1965/1966, Bley had already perfected his mature style. The herky-jerky evolution he brought to his own compositions reflects those of his ex-wife Carla Bley plus Thelonious Monk’s quirkiness. Other tracks written by Carla or his then-wife Annette Peacock delineate phraseology that moves from animated runs on bouncy tunes to paused interludes on the slower numbers. These trio sessions also make particular use of Barry Altschul’s drumming. As the pianist varies the exposition with theme repetitions and unexpected asides, powerful press rolls, cymbal pops and reverb help preserve the tracks’ broken-chord evolution. A gentle ballad like Touching gives space to bassist Kent Carter’s widening plucks, with keyboard rumbles added for a dramatic interchange. Peacock’s writing is most spidery on Both, with the narrative created as shaded keyboard tones vibrate at quicker and quicker speeds alongside overt drum ruffs. On the other hand the almost-19-minute Blood from a year later with Mark Levinson on bass is more overtly rhythmic as the bassist and Altschul shake and rustle alongside Bley’s theme depiction. The pianist first outlines the exposition with hand pressure, adds thickening variations mirrored by drum ruffs and concludes with a dramatic keyboard flourish. Fluctuating between methodical and munificent, Closer and Pablo, two Bley originals, display the resolved contradictions in his playing and writing. Driven by single notes, the former is atmospheric and animated, working through muted expression; it swings without increasing the tempo. Just the opposite, Pablo rolls out a piano introduction that is as hard and heavy as Carter’s caustic pizzicato stops and Altschul’s smacks and tone shattering. The finale contrasts Bley’s rolling narrative with Altschul’s clips, rolls and ratamacues.

By the time Touching & Blood Revisited (ezz-thetics 1108 hathut.com) was recorded in 1965/1966, Bley had already perfected his mature style. The herky-jerky evolution he brought to his own compositions reflects those of his ex-wife Carla Bley plus Thelonious Monk’s quirkiness. Other tracks written by Carla or his then-wife Annette Peacock delineate phraseology that moves from animated runs on bouncy tunes to paused interludes on the slower numbers. These trio sessions also make particular use of Barry Altschul’s drumming. As the pianist varies the exposition with theme repetitions and unexpected asides, powerful press rolls, cymbal pops and reverb help preserve the tracks’ broken-chord evolution. A gentle ballad like Touching gives space to bassist Kent Carter’s widening plucks, with keyboard rumbles added for a dramatic interchange. Peacock’s writing is most spidery on Both, with the narrative created as shaded keyboard tones vibrate at quicker and quicker speeds alongside overt drum ruffs. On the other hand the almost-19-minute Blood from a year later with Mark Levinson on bass is more overtly rhythmic as the bassist and Altschul shake and rustle alongside Bley’s theme depiction. The pianist first outlines the exposition with hand pressure, adds thickening variations mirrored by drum ruffs and concludes with a dramatic keyboard flourish. Fluctuating between methodical and munificent, Closer and Pablo, two Bley originals, display the resolved contradictions in his playing and writing. Driven by single notes, the former is atmospheric and animated, working through muted expression; it swings without increasing the tempo. Just the opposite, Pablo rolls out a piano introduction that is as hard and heavy as Carter’s caustic pizzicato stops and Altschul’s smacks and tone shattering. The finale contrasts Bley’s rolling narrative with Altschul’s clips, rolls and ratamacues.

Although defining experiences in more energetic improvising with Sonny Rollins and others would be in the future, the introspective approach in Bley’s developed style resulted from the two years he was in Jimmy Giuffre’s chamber-jazz trio. With only Bley’s piano and Steve Swallow’s bass backing him, the clarinetist created introspective miniatures that emphasized mood over motion. Free Fall Clarinet 1962 Revisited (ezz-thetics 1119 hathut.com) was the final session before the trio disbanded. Like the subsequent fame of the Velvet Undergound’s LPs, the Giuffe3’s sets were neglected in the early 1960s, but have since been recognized as the template for much subsequent free music. Giuffre projects his astringent a cappella clarinet solos with squeaks and peeps, yet his extended glissandi without pause on a track like Dichotomy presage circular breathing passages that are now almost commonplace. Not only did the group not include a drummer, but also (for the most part) avoided pulse and melody. Instead, eccentric harmony predominated, marked by Bley’s key clips and Swallow’s intermittent string pumps. Sticking to clarion or higher registers, Giuffre’s flutter tonguing and splayed trills connect often enough with keyboard pressure to keep tracks linear as on Spasmodic. At the same time his playing is often wide bore enough to suggest tonal extensions with interludes like that on Threewe completed against a backdrop of double bass plucks. Unlike Bley’s agitated minimalist asides, Swallow’s only solo is on Divided Man, and even there shares space with mid-range clarinet breaths. With those antecedents, the ten-minute The Five Ways seems like a swing session. Double bass bounces and low-pitched piano colouration introduce the piece which goes through numerous transitions. A piano crescendo introduces three-part modulations that lead to sprightly storytelling from Giuffre, with the track finally climaxing with a high-pitched reed slur, almost replicating the one which began the album.

Although defining experiences in more energetic improvising with Sonny Rollins and others would be in the future, the introspective approach in Bley’s developed style resulted from the two years he was in Jimmy Giuffre’s chamber-jazz trio. With only Bley’s piano and Steve Swallow’s bass backing him, the clarinetist created introspective miniatures that emphasized mood over motion. Free Fall Clarinet 1962 Revisited (ezz-thetics 1119 hathut.com) was the final session before the trio disbanded. Like the subsequent fame of the Velvet Undergound’s LPs, the Giuffe3’s sets were neglected in the early 1960s, but have since been recognized as the template for much subsequent free music. Giuffre projects his astringent a cappella clarinet solos with squeaks and peeps, yet his extended glissandi without pause on a track like Dichotomy presage circular breathing passages that are now almost commonplace. Not only did the group not include a drummer, but also (for the most part) avoided pulse and melody. Instead, eccentric harmony predominated, marked by Bley’s key clips and Swallow’s intermittent string pumps. Sticking to clarion or higher registers, Giuffre’s flutter tonguing and splayed trills connect often enough with keyboard pressure to keep tracks linear as on Spasmodic. At the same time his playing is often wide bore enough to suggest tonal extensions with interludes like that on Threewe completed against a backdrop of double bass plucks. Unlike Bley’s agitated minimalist asides, Swallow’s only solo is on Divided Man, and even there shares space with mid-range clarinet breaths. With those antecedents, the ten-minute The Five Ways seems like a swing session. Double bass bounces and low-pitched piano colouration introduce the piece which goes through numerous transitions. A piano crescendo introduces three-part modulations that lead to sprightly storytelling from Giuffre, with the track finally climaxing with a high-pitched reed slur, almost replicating the one which began the album.

Malleability and volume may have predisposed Swallow’s shift to the five-string electric bass guitar in the early 1970s, and at 81 he’s still playing in a more audible, but just as tasteful fashion. On Eightfold Path (Little (i) music littleimusic.com) he’s part of the Sunwatcher Quartet. Leader, tenor saxophonist Jeff Lederer, and the other players, organist/pianist Jamie Saft and drummer Matt Wilson, are two or three decades younger than the bassist. No matter, Swallow’s echoing frails provide these tracks with bedrock, and all put a 21st-century sheen on soul jazz. Boisterous, where Giuffre’s sound was muted, most tracks pulsate with jumping organ runs coupled with the saxophonist’s energetic cries and split tones that mate Albert Ayler and Lockjaw Davis. With the drummer’s rugged shuffles or backbeats, the few piano-accompanied ballads like Right Effort also find Lederer flutter tonguing changes that are both mellow and barbed. More typical are tunes such as Right Resolve where saxophone honks and bass guitar pops glue the bottom alongside Saft’s herky-jerky tremors, creating a bluesy afterimage. Add in Wilson’s stop-time drumming and the image presented is of a good-time after-hours party somehow interrupted by austere free jazz multiphonics. That’s also why Right Action stands out with post-modern insouciance. Using Swallow’s continuous patterns as rhythmic glue, Wilson’s tambourine-on-hi-hat-splashes take on a Latin tinge while the saxophonist’s extended altissimo screams seem to relate as much to pioneering rock’n’roll tenor saxist Big Jay McNeely as to free jazz proponents like Ayler.

Malleability and volume may have predisposed Swallow’s shift to the five-string electric bass guitar in the early 1970s, and at 81 he’s still playing in a more audible, but just as tasteful fashion. On Eightfold Path (Little (i) music littleimusic.com) he’s part of the Sunwatcher Quartet. Leader, tenor saxophonist Jeff Lederer, and the other players, organist/pianist Jamie Saft and drummer Matt Wilson, are two or three decades younger than the bassist. No matter, Swallow’s echoing frails provide these tracks with bedrock, and all put a 21st-century sheen on soul jazz. Boisterous, where Giuffre’s sound was muted, most tracks pulsate with jumping organ runs coupled with the saxophonist’s energetic cries and split tones that mate Albert Ayler and Lockjaw Davis. With the drummer’s rugged shuffles or backbeats, the few piano-accompanied ballads like Right Effort also find Lederer flutter tonguing changes that are both mellow and barbed. More typical are tunes such as Right Resolve where saxophone honks and bass guitar pops glue the bottom alongside Saft’s herky-jerky tremors, creating a bluesy afterimage. Add in Wilson’s stop-time drumming and the image presented is of a good-time after-hours party somehow interrupted by austere free jazz multiphonics. That’s also why Right Action stands out with post-modern insouciance. Using Swallow’s continuous patterns as rhythmic glue, Wilson’s tambourine-on-hi-hat-splashes take on a Latin tinge while the saxophonist’s extended altissimo screams seem to relate as much to pioneering rock’n’roll tenor saxist Big Jay McNeely as to free jazz proponents like Ayler.

Like Swallow, Barry Altschul had been germane to Bley’s trio music, but over the years he’s worked with numerous other advanced musicians. Now 78, Long Tall Sunshine (NotTwo MW 1012-2 nottwo.com) by his 3DOM Factor features his compositions played by the drummer plus saxophonist/clarinetist Jon Irabagon and bassist Joe Fonda, whose broad woody strokes open this live set. Energy music of the highest order, there’s delicacy here as well as dissonance. These attributes also emanate from the drummer, who on the eponymous first track and especially the final, Martin’s Stew, projects solos that thunder with taste. Pounding rim shots, clanking cymbals and bass drum rumbles cement the beat without unnecessary volume and quickly lock in with Fonda’s logical pumps and arco asides. Outlining and recapping the theme here and elsewhere, Irabagon races through a compendium of staccato squawks, yelping bites and altissimo burbles. His a cappella deconstruction of the title tune with foghorn-like honks, key percussion and strangled yelps is like aural sleight of hand. Extended techniques appear almost before you realize it and they ease into a more standard playing before the finale. Irabagon’s ability to source phrase after phrase and tone after tone in expanding and extended fashion is complemented by Altschul’s composition. As outside as they become with reed split tones, percussion splatters and weighty string slithering, a kernel of melody is referred to on and off. Fragmented quotes from disguised modern jazz classics lurk just below the surface and are heard in the saxophonist’s theme statements and asides.

Like Swallow, Barry Altschul had been germane to Bley’s trio music, but over the years he’s worked with numerous other advanced musicians. Now 78, Long Tall Sunshine (NotTwo MW 1012-2 nottwo.com) by his 3DOM Factor features his compositions played by the drummer plus saxophonist/clarinetist Jon Irabagon and bassist Joe Fonda, whose broad woody strokes open this live set. Energy music of the highest order, there’s delicacy here as well as dissonance. These attributes also emanate from the drummer, who on the eponymous first track and especially the final, Martin’s Stew, projects solos that thunder with taste. Pounding rim shots, clanking cymbals and bass drum rumbles cement the beat without unnecessary volume and quickly lock in with Fonda’s logical pumps and arco asides. Outlining and recapping the theme here and elsewhere, Irabagon races through a compendium of staccato squawks, yelping bites and altissimo burbles. His a cappella deconstruction of the title tune with foghorn-like honks, key percussion and strangled yelps is like aural sleight of hand. Extended techniques appear almost before you realize it and they ease into a more standard playing before the finale. Irabagon’s ability to source phrase after phrase and tone after tone in expanding and extended fashion is complemented by Altschul’s composition. As outside as they become with reed split tones, percussion splatters and weighty string slithering, a kernel of melody is referred to on and off. Fragmented quotes from disguised modern jazz classics lurk just below the surface and are heard in the saxophonist’s theme statements and asides.

During Bley’s 1990s tenure at the NEC, one student who stood out was Japanese pianist Satoko Fujii, whose first American disc in 1996 was a duo with Bley. Now involved with ensembles ranging from duos to big bands, you can sense the Canadian pianist’s influence and how Fujii evolved from it when she heads a trio. Moon on the Lake (Libra Records 203-065 librarecords.com) with her Tokyo Trio is completed by bassist/cellist Takashi Sugawa and drummer Ittetsu Takemura. Taking from both the mainstream and the avant garde, she allows ideas to squirm along the piano keys and sometimes dips inside the frame to pluck the strings for added resonance. Quick to feature her partners, she plays percussively to match Takemura’s clanking rolls and whistling ruffs or slowly, chords to extract the proper colours alongside temple bell-like cymbal vibration, or the trembling pulls of Sugawa’s formalist arco work. While the title – and final – tune is quiet and romantic, individual internal string plucks and a dry processional pace prevents it from sinking into sentimentality. Keep Running, and especially the extended Aspiration on the other hand, are progressively dissonant. Beginning with spinning drum top raps, then press rolls, the former tune gains its broken chord shape as the pianist pounds out kinetic patterns with one hand and relaxed fingering with the other. The narrative climaxes with rifle-shot-like pops from the drummer. Aspiration sums up both sides of her keyboard personality. From slow and stately her chording works up to florid impressionism and then relaxes into low-pitched shakes mated with the cello’s mournful interlocution. Later, barely there cymbal shuffles and rim shots accelerate to woody thumps and pumps as Fujii’s stopped piano keys unearth a spreading metronomic rhythm. Reaching a crescendo of allegro key pummeling seconded by metallic percussion rattles and rugged bass string plucks, the piece sinks back to its lento beginning framed with single piano notes.

During Bley’s 1990s tenure at the NEC, one student who stood out was Japanese pianist Satoko Fujii, whose first American disc in 1996 was a duo with Bley. Now involved with ensembles ranging from duos to big bands, you can sense the Canadian pianist’s influence and how Fujii evolved from it when she heads a trio. Moon on the Lake (Libra Records 203-065 librarecords.com) with her Tokyo Trio is completed by bassist/cellist Takashi Sugawa and drummer Ittetsu Takemura. Taking from both the mainstream and the avant garde, she allows ideas to squirm along the piano keys and sometimes dips inside the frame to pluck the strings for added resonance. Quick to feature her partners, she plays percussively to match Takemura’s clanking rolls and whistling ruffs or slowly, chords to extract the proper colours alongside temple bell-like cymbal vibration, or the trembling pulls of Sugawa’s formalist arco work. While the title – and final – tune is quiet and romantic, individual internal string plucks and a dry processional pace prevents it from sinking into sentimentality. Keep Running, and especially the extended Aspiration on the other hand, are progressively dissonant. Beginning with spinning drum top raps, then press rolls, the former tune gains its broken chord shape as the pianist pounds out kinetic patterns with one hand and relaxed fingering with the other. The narrative climaxes with rifle-shot-like pops from the drummer. Aspiration sums up both sides of her keyboard personality. From slow and stately her chording works up to florid impressionism and then relaxes into low-pitched shakes mated with the cello’s mournful interlocution. Later, barely there cymbal shuffles and rim shots accelerate to woody thumps and pumps as Fujii’s stopped piano keys unearth a spreading metronomic rhythm. Reaching a crescendo of allegro key pummeling seconded by metallic percussion rattles and rugged bass string plucks, the piece sinks back to its lento beginning framed with single piano notes.

Unlike others, there will never be a Bley school of improvisation. Yet musicians like Fujii continue to build on his ideas and guidance and many of his associates are still producing notable advanced music.