Editor's Corner - July 2022

Here we are at the summer issue, the final installment of Volume 27 (the completion of our 27th year of publishing The WholeNote). This means my last chance until September to try to make it through the pile of excellent discs that have caught my attention. I have winnowed them down to a top ten, but even so I will be hard pressed to cover them all within my allotted space. Of course it would be a much simpler task if I restricted myself to talking more about the discs and less about my own connections to them, but as regular readers know, the chances of that are slim at best.

The latest release by Montreal’s Quatuor Molinari is Philip Glass – Complete String Quartets Volume One (ATMA ACD2 4071 atmaclassique.com/en). Glass continues to add to the repertoire – he has eight quartets so far – heedless of those artists who have already published “complete” recordings. The first four are arranged here in a non-sequential, but quite effective order. String Quartet No.2 “Company” – with its haunting opening – is first up, followed by No.3 “Mishima” which was adapted from the soundtrack of the film by that name. Both of these works reflect Glass’ mature minimalism and it comes as a bit of shock when they are followed by his first venture into the genre, written in 1966 before he developed his signature style. This quartet is more angular and searching, although it too features a cyclical return to its starting point, a feature that the notes point out may “evoke for some the mythical Sisyphus, condemned to eternal repetition.” String Quartet No.4 “Buczak” – commissioned as a memorial for artist Brian Buczak – returns us to more familiar ground – its slow movement is even reminiscent of the opening of the second quartet – and brings an intriguing disc to a fitting close.

The latest release by Montreal’s Quatuor Molinari is Philip Glass – Complete String Quartets Volume One (ATMA ACD2 4071 atmaclassique.com/en). Glass continues to add to the repertoire – he has eight quartets so far – heedless of those artists who have already published “complete” recordings. The first four are arranged here in a non-sequential, but quite effective order. String Quartet No.2 “Company” – with its haunting opening – is first up, followed by No.3 “Mishima” which was adapted from the soundtrack of the film by that name. Both of these works reflect Glass’ mature minimalism and it comes as a bit of shock when they are followed by his first venture into the genre, written in 1966 before he developed his signature style. This quartet is more angular and searching, although it too features a cyclical return to its starting point, a feature that the notes point out may “evoke for some the mythical Sisyphus, condemned to eternal repetition.” String Quartet No.4 “Buczak” – commissioned as a memorial for artist Brian Buczak – returns us to more familiar ground – its slow movement is even reminiscent of the opening of the second quartet – and brings an intriguing disc to a fitting close.

This Molinari release is digital only at the moment, but on completion of Volume Two, ATMA says they will be issued together as a double CD. Although founder Olga Ranzenhofer is the only remaining original member of the quartet, which has undergone myriad personnel changes in its 25-year history, the Molinari sound remains consistent and exemplary, and their dedication to contemporary repertoire is outstanding. Molinari’s impressive discography now numbers 14 in the ATMA catalogue, and includes such international luminaries as Gubaidulina, Schnittke, Penderecki, Kurtág and Zorn, along with Canadians Jean-Papineau Couture, Petros Shoujounian and the 12 quartets of R. Murray Schafer.

Listen to 'Philip Glass – Complete String Quartets Volume One' Now in the Listening Room

Canadian Soundscapes: Schafer; Raminsh; Schneider (CMCCD29722 cmccanada.org/shop/cd-cmccd-29722) opens with The Falcon’s Trumpet, a concerto R. Murray Schafer wrote for Stuart Laughton, a longtime participant in Schafer’s Wolf Project in the Haliburton Forest. Schafer wrote the piece while working at Strasbourg University in France and says “no doubt my nostalgia for Canadian lakes and forests strongly influenced the conception of this piece.” Certainly it is evocative of the wilderness, as the trumpet soars above the orchestra like a falcon in flight. In this performance soloist Guy Few joins the Okanagan Symphony Orchestra (OSO) under the direction of Rosemary Thomson. Thomson has been music director of the OSO since 2006, previously serving as assistant conductor of the Canadian Opera Company and conductor-in-residence of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. The OSO is the third largest professional orchestra in B.C. and this is its inaugural recording. A striking feature of Schafer’s concerto is the wordless soprano obbligato in the final minute, in this instance sung by Carmen Harris. Perhaps more surprising, considering Schafer has frequently used high sopranos in his wilderness pieces, is the inclusion of a soprano in a vocalise duet with the soloist in Imant Raminsh’s Violin Concerto. Raminsh, best known and well-loved for his lush choral music, says he felt some trepidation when approached to write a piece for Vancouver Symphony Orchestra concertmaster Robert Davidovici. He felt no affinity for works of “flash and little substance” but ultimately felt comfortable creating something “more along the Brahmsian line – a symphonic work with solo violin obbligato.” At more than 40 minutes in four movements, it is truly grand in scope and lusciously Romantic in sensibility. Soprano Eeva-Maria Kopp is first heard in the final minute of the Agitato Appassionato movement and throughout the following Andante con moto. She re-enters briefly towards the end of the Con Spirito finale. The shared timbres are scintillating and violinist Melissa Williams shines throughout this remarkable work. Ernst Schneider’s self-proclaimed Romantic Piano Concerto is the earliest piece here, dating from 1980, at a time when the composer was immersing himself in the study of piano concerti of the Baroque, classical and Romantic eras. It is just as advertised and young Canadian soloist Jaeden Izik-Dzurko rises to the occasion admirably. I was particularly taken with the Adagio Molto Espressivo second movement, to my ears reminiscent of the same movement in Ravel’s Concerto in G.

Canadian Soundscapes: Schafer; Raminsh; Schneider (CMCCD29722 cmccanada.org/shop/cd-cmccd-29722) opens with The Falcon’s Trumpet, a concerto R. Murray Schafer wrote for Stuart Laughton, a longtime participant in Schafer’s Wolf Project in the Haliburton Forest. Schafer wrote the piece while working at Strasbourg University in France and says “no doubt my nostalgia for Canadian lakes and forests strongly influenced the conception of this piece.” Certainly it is evocative of the wilderness, as the trumpet soars above the orchestra like a falcon in flight. In this performance soloist Guy Few joins the Okanagan Symphony Orchestra (OSO) under the direction of Rosemary Thomson. Thomson has been music director of the OSO since 2006, previously serving as assistant conductor of the Canadian Opera Company and conductor-in-residence of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. The OSO is the third largest professional orchestra in B.C. and this is its inaugural recording. A striking feature of Schafer’s concerto is the wordless soprano obbligato in the final minute, in this instance sung by Carmen Harris. Perhaps more surprising, considering Schafer has frequently used high sopranos in his wilderness pieces, is the inclusion of a soprano in a vocalise duet with the soloist in Imant Raminsh’s Violin Concerto. Raminsh, best known and well-loved for his lush choral music, says he felt some trepidation when approached to write a piece for Vancouver Symphony Orchestra concertmaster Robert Davidovici. He felt no affinity for works of “flash and little substance” but ultimately felt comfortable creating something “more along the Brahmsian line – a symphonic work with solo violin obbligato.” At more than 40 minutes in four movements, it is truly grand in scope and lusciously Romantic in sensibility. Soprano Eeva-Maria Kopp is first heard in the final minute of the Agitato Appassionato movement and throughout the following Andante con moto. She re-enters briefly towards the end of the Con Spirito finale. The shared timbres are scintillating and violinist Melissa Williams shines throughout this remarkable work. Ernst Schneider’s self-proclaimed Romantic Piano Concerto is the earliest piece here, dating from 1980, at a time when the composer was immersing himself in the study of piano concerti of the Baroque, classical and Romantic eras. It is just as advertised and young Canadian soloist Jaeden Izik-Dzurko rises to the occasion admirably. I was particularly taken with the Adagio Molto Espressivo second movement, to my ears reminiscent of the same movement in Ravel’s Concerto in G.

The Canadian Music Centre’s latest release is a digital EP, Mascarada by Alice Ping Yee Ho (Centrediscs CMCCD 29922 cmccanada.org/shop/cd-cmccd-29922) featuring cellist Rachel Mercer, flamenco dancer Cyrena Luchkow-Huang and the Allegra Chamber Orchestra under Janna Sailor. The press release included a link to a video of Mascarada (youtube.com/watch?v=3hb7fvsAJ2o) and at first I was confused as to whether this was a video or an audio release. It seemed strange to credit a dancer in an audio-only recording, but once you hear it you will understand why. The flamboyant, percussive choreography is an integral part of the composition and is very present on the recording. Watching the video where all the performers are masked and socially distanced, it seems likely that this is yet another result of the current pandemic, but it is also an apt touch for a piece called a masquerade. Ho has successfully captured the flamenco spirit and it could just as easily have been called “My Spanish Heart.” I first met Mercer as a young artist while working as a music programmer at CJRT-FM in the early 90s. Since that time she has gone on to a stellar solo and chamber career, and now serves as principal cellist for Canada’s National Arts Centre Orchestra. She shares the spotlight with Luchkow-Huang here, and it’s hard to decide who is stealing the show from whom in this stunning performance.

The Canadian Music Centre’s latest release is a digital EP, Mascarada by Alice Ping Yee Ho (Centrediscs CMCCD 29922 cmccanada.org/shop/cd-cmccd-29922) featuring cellist Rachel Mercer, flamenco dancer Cyrena Luchkow-Huang and the Allegra Chamber Orchestra under Janna Sailor. The press release included a link to a video of Mascarada (youtube.com/watch?v=3hb7fvsAJ2o) and at first I was confused as to whether this was a video or an audio release. It seemed strange to credit a dancer in an audio-only recording, but once you hear it you will understand why. The flamboyant, percussive choreography is an integral part of the composition and is very present on the recording. Watching the video where all the performers are masked and socially distanced, it seems likely that this is yet another result of the current pandemic, but it is also an apt touch for a piece called a masquerade. Ho has successfully captured the flamenco spirit and it could just as easily have been called “My Spanish Heart.” I first met Mercer as a young artist while working as a music programmer at CJRT-FM in the early 90s. Since that time she has gone on to a stellar solo and chamber career, and now serves as principal cellist for Canada’s National Arts Centre Orchestra. She shares the spotlight with Luchkow-Huang here, and it’s hard to decide who is stealing the show from whom in this stunning performance.

I will venture out of my field of expertise for this next one, but not so much out of my comfort zone. Joel Quarrington – The Music of Don Thompson (Modica Music joelquarrington.com/store) is a fabulous collaboration between two of Canada’s top musicians. Although the overall feel of the disc is rooted in Thompson’s more-than-half-century career as jazz bass, vibes and piano player, he is featured here as composer and accompanist to Quarrington, a world-renowned musician who has served as principal double bass player for the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto Symphony, Canada’s National Arts Centre Orchestra and most recently the London Symphony Orchestra. The first four tracks feature Quarrington with Thompson on piano, beginning with Thompson’s arrangement of the classic A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square, followed by three Thompson originals. Quarrington’s tone is sumptuous and his ability to swing is truly impressive, as rarely heard from a classical musician.

I will venture out of my field of expertise for this next one, but not so much out of my comfort zone. Joel Quarrington – The Music of Don Thompson (Modica Music joelquarrington.com/store) is a fabulous collaboration between two of Canada’s top musicians. Although the overall feel of the disc is rooted in Thompson’s more-than-half-century career as jazz bass, vibes and piano player, he is featured here as composer and accompanist to Quarrington, a world-renowned musician who has served as principal double bass player for the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto Symphony, Canada’s National Arts Centre Orchestra and most recently the London Symphony Orchestra. The first four tracks feature Quarrington with Thompson on piano, beginning with Thompson’s arrangement of the classic A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square, followed by three Thompson originals. Quarrington’s tone is sumptuous and his ability to swing is truly impressive, as rarely heard from a classical musician.

The album notes comprise an extended reminiscence from Thompson in which he tells of early meetings with Quarrington and how their paths continued to cross over the years. One example was in 1989 when Quarrington asked him to write a piece for a gig he was doing for New Music Concerts involving multiple bass players, including Wolfgang Güttler, principal of the SWR Symphony Orchestra, Baden-Baden and Freiburg. The result was Quartet 89 for four double basses. Thompson, who was to play pizzicato in the ensemble, says “I knew I couldn’t write a real ‘classical’ piece, so I just tried to come up with something we could play that might be fun. I wrote a big part for myself with a solo intro, a solo in the middle plus a cadenza, and left it up to the rest of them to decide who played [what].” I was at that concert, although it was before my association with NMC began, and I can tell you they had fun indeed. In the current iteration, which completes the disc, Thompson sits out and Roberto Occhipinti takes his spot with aplomb, and great sound, with Quarrington, Joseph Phillips and Travis Harrison on the arco parts. Not a classical piece per se, but somewhere between that and the world of jazz with a foot in both camps, much like this unique collaboration.

Another disc that falls between two worlds is Im Wald conceived by, and featuring, pianist Benedetto Boccuzzi (Digressione Music DCTT126 digressionemusic.it). In this instance the two worlds are the piano music of the late classical/early Romantic era, juxtaposed with contemporary works by Jörg Widmann, Wolfgang Rihm and Helmut Lachenmann. While purists will likely be offended by the imposition of sometimes abrasive works into such beloved cycles as Schumann’s Waldszenen and Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin (in a piano arrangement) I personally find it refreshing and even invigorating. The first half of the disc involves a complete performance of the Schumann (Forest Scenes in English) with selected movements from Widmann’s Elf Humoresken (11 Humoresques) interspersed. Then as a “palette cleanser” Boccuzzi inserts an electronic soundscape of his own creation, Im Wald (Into the Woods). In the second half of the disc we hear eight of the 20 movements of the Schubert, this time “interrupted” by a Ländler by Rihm and Fünf Variationen über ein Thema von Schubert (not from Die schöne Müllerin) by Lachenmann. This latter is of particular interest to me as it is an early melodic work (1956) that predates the mature style I am familiar with in which Lachenmann focuses mainly on extra-musical timbres achieved through extended instrumental techniques. Boccuzzi is to be congratulated not only for the overall design of this project, but for his understanding and convincing realization of the varying esthetics of these diverse composers.

Another disc that falls between two worlds is Im Wald conceived by, and featuring, pianist Benedetto Boccuzzi (Digressione Music DCTT126 digressionemusic.it). In this instance the two worlds are the piano music of the late classical/early Romantic era, juxtaposed with contemporary works by Jörg Widmann, Wolfgang Rihm and Helmut Lachenmann. While purists will likely be offended by the imposition of sometimes abrasive works into such beloved cycles as Schumann’s Waldszenen and Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin (in a piano arrangement) I personally find it refreshing and even invigorating. The first half of the disc involves a complete performance of the Schumann (Forest Scenes in English) with selected movements from Widmann’s Elf Humoresken (11 Humoresques) interspersed. Then as a “palette cleanser” Boccuzzi inserts an electronic soundscape of his own creation, Im Wald (Into the Woods). In the second half of the disc we hear eight of the 20 movements of the Schubert, this time “interrupted” by a Ländler by Rihm and Fünf Variationen über ein Thema von Schubert (not from Die schöne Müllerin) by Lachenmann. This latter is of particular interest to me as it is an early melodic work (1956) that predates the mature style I am familiar with in which Lachenmann focuses mainly on extra-musical timbres achieved through extended instrumental techniques. Boccuzzi is to be congratulated not only for the overall design of this project, but for his understanding and convincing realization of the varying esthetics of these diverse composers.

Listen to 'Im Wald' Now in the Listening Room

Speaking of Die schöne Müllerin, I was surprised when no one spoke up when I offered Gerald Finley’s new Hyperion recording with Julius Drake to my team of reviewers (CDA68377 hyperion-records.co.uk/dw.asp?dc=W1922_68377). I was also surprised to find that the renowned Canadian bass baritone had not previously recorded the cycle, familiar as I am with his other fine Schubert recordings. As we have come to expect from Finley and Drake’s impeccable performances of Winterreise and Schwanengesang, this latest release is everything one could ask for: nuanced, emotionally moving, pitch-perfect and well balanced. Finley is in top form and Drake is the perfect partner.

Speaking of Die schöne Müllerin, I was surprised when no one spoke up when I offered Gerald Finley’s new Hyperion recording with Julius Drake to my team of reviewers (CDA68377 hyperion-records.co.uk/dw.asp?dc=W1922_68377). I was also surprised to find that the renowned Canadian bass baritone had not previously recorded the cycle, familiar as I am with his other fine Schubert recordings. As we have come to expect from Finley and Drake’s impeccable performances of Winterreise and Schwanengesang, this latest release is everything one could ask for: nuanced, emotionally moving, pitch-perfect and well balanced. Finley is in top form and Drake is the perfect partner.

I was unfamiliar with the Bergamot Quartet before their recording In the Brink (New Focus Recordings FCR316 newfocusrecordings.com). Founded at the Peabody Institute in Baltimore in 2016, the quartet is “fueled by a passion for exploring and advocating for the music of living composers” and this disc is certainly a testament to that. It opens with a work by American cellist and composer Paul Wiancko, commissioned by the Banff Centre for the Toronto-based Eybler Quartet during the 2019 Evolution of the Quartet festival and conference. (The Eybler were on the faculty and the Bergamot were participants in the program that year.) Ode on a Broken Loom is evocative of a spinning wheel and its rhythmic drive is compelling. Tania Léon’s Esencia (2009) is a three-movement work that incorporates influences from the Caribbean and Latino America, cross-pollinated with Coplandesque harmonic overtones. Suzanne Farrin’s Undecim (2006) is the earliest work here, and is in some ways the most intriguing. The composer says it was written “when I was thinking about how memory could be applied as a process in my music. I was fascinated by the long lifespan of stringed instruments. In this work, I liked to imagine that the bow remembers all of the repertoire of its past and could […] utter articulations of older pieces in an ephemeral, non-linear [gloss on] the present.” It’s a wild ride. The final work, the group’s first commission, is by first violinist Ledah Finck. In the Brink (2019) adds a drum set (Terry Feeney) to the ensemble, and requires the string players to vocalise, exclaim and whisper while playing. Not your traditional string quartet!

I was unfamiliar with the Bergamot Quartet before their recording In the Brink (New Focus Recordings FCR316 newfocusrecordings.com). Founded at the Peabody Institute in Baltimore in 2016, the quartet is “fueled by a passion for exploring and advocating for the music of living composers” and this disc is certainly a testament to that. It opens with a work by American cellist and composer Paul Wiancko, commissioned by the Banff Centre for the Toronto-based Eybler Quartet during the 2019 Evolution of the Quartet festival and conference. (The Eybler were on the faculty and the Bergamot were participants in the program that year.) Ode on a Broken Loom is evocative of a spinning wheel and its rhythmic drive is compelling. Tania Léon’s Esencia (2009) is a three-movement work that incorporates influences from the Caribbean and Latino America, cross-pollinated with Coplandesque harmonic overtones. Suzanne Farrin’s Undecim (2006) is the earliest work here, and is in some ways the most intriguing. The composer says it was written “when I was thinking about how memory could be applied as a process in my music. I was fascinated by the long lifespan of stringed instruments. In this work, I liked to imagine that the bow remembers all of the repertoire of its past and could […] utter articulations of older pieces in an ephemeral, non-linear [gloss on] the present.” It’s a wild ride. The final work, the group’s first commission, is by first violinist Ledah Finck. In the Brink (2019) adds a drum set (Terry Feeney) to the ensemble, and requires the string players to vocalise, exclaim and whisper while playing. Not your traditional string quartet!

Listen to 'In the Brink' Now in the Listening Room

The San Antonio-based SOLI Chamber Ensemble has been championing contemporary music since their founding in 1994. They are comprised of violin, clarinet, cello and piano, the formation immortalized in Messiaen’s iconic Quatuor pour la fin du temps. Their latest CD presents The Clearing and the Forest (Acis APL50069 acisproductions.com), “an evening-length, staged work that dramatizes the relationship between landscape, migration and refuge through music, theater and sculpture” by Scott Ordway. A very brief Prologue featuring quiet wind chimes leads into Act I – we must leave this place forever in five instrumental sections, mostly calm but with occasional clarinet and violin shrieks reminiscent of ecstatic passages in Messiaen’s work. The six-movement Act II – we must run like wolves to the end begins with quiet solo clarinet, once again echoing Messiaen. In Ordway’s defence it must be virtually impossible to write for this combination of instruments without referring to that master; however, there is much original writing here in Ordway’s own voice. A contemplative Intermezzo – a prayer of thanksgiving leads to the final Act III – the things we lost we will never reclaim. This single extended movement gradually builds and builds before receding and fading once again into the sound of chimes. Ordway says “I have tried to create a work which honors and embodies the values of welcoming, of care and concern for others, of keen attention to the small and secret phenomena unfolding around us in the living world every day.” I would say he has succeeded, as has the SOLI Ensemble in bringing this work to life.

I first listened to Vicky Chow’s CD Sierra (Cantaloupe Music CA21174 cantaloupemusic.com/albums/sierra) without reading the press release or the program notes and initially assumed I was hearing a remarkable piano solo. It turns out however that the compositions by Jane Antonia Cornish presented here are actually works for multiple pianos (up to six) with all the parts overdubbed by Chow in the studio. The lush, and luscious, pieces are beautifully performed, their multiple layers seamlessly interwoven to produce an entrancing experience. The five pieces, Sky, Ocean, Sunglitter, Last Light and the extended title work for four pianos, comprise a meditative, bell-like suite that I found perfect for releasing the tensions of everyday tribulations. Hmm, tintinnabulations as antidote to tribulations, I like that.

I first listened to Vicky Chow’s CD Sierra (Cantaloupe Music CA21174 cantaloupemusic.com/albums/sierra) without reading the press release or the program notes and initially assumed I was hearing a remarkable piano solo. It turns out however that the compositions by Jane Antonia Cornish presented here are actually works for multiple pianos (up to six) with all the parts overdubbed by Chow in the studio. The lush, and luscious, pieces are beautifully performed, their multiple layers seamlessly interwoven to produce an entrancing experience. The five pieces, Sky, Ocean, Sunglitter, Last Light and the extended title work for four pianos, comprise a meditative, bell-like suite that I found perfect for releasing the tensions of everyday tribulations. Hmm, tintinnabulations as antidote to tribulations, I like that.

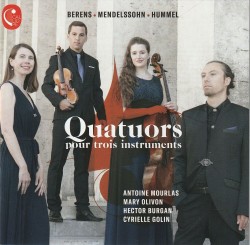

I did not know what to expect from the title Quatuors pour trois instruments (Calliope Records CAL2195 calliope-records.com). I am familiar with trio sonatas – which, while called trios, actually require four musicians, two melody instruments and continuo often made up of a keyboard and a bass, kind of a Baroque rhythm section – but in this instance “quartet for three instruments” refers to a piano trio – violin, cello and piano – with two players in piano four hands formation. Evidently it was a common 19th-century grouping, which has since virtually disappeared. Violinist Hector Burgan and cellist Cyrielle Golin are joined by Antoine Mourlas and Mary Olivon sharing the piano bench in delightful multi-movement works by Hermann Berens (1826-1880) and Ferdinand Hummel (1855-1928). (Hummel is not related to Johann Nepomuk Hummel, the only composer of that name of whom I was previously aware.) The only composer represented here whom I did recognize is Felix Mendelssohn, whose Ruy Blas Overture was written in 1839 for a Leipzig production of Victor Hugo’s play of the same name. Fresh and sprightly, Hummel’s Sérénade Im Frühling from 1884 depicts Vienna in sunny springtime, while Berens’ two quartets from the 1860s are in a more classical style, harkening back to the aforementioned Mendelssohn. I was initially concerned that the four hands on the piano would make for muddy textures, hiding the two string instruments, but these well-balanced performances put the lie to that. I’m pleased to have made the acquaintance of these composers, and these fine players, in this great introduction to some little-known repertoire.

I did not know what to expect from the title Quatuors pour trois instruments (Calliope Records CAL2195 calliope-records.com). I am familiar with trio sonatas – which, while called trios, actually require four musicians, two melody instruments and continuo often made up of a keyboard and a bass, kind of a Baroque rhythm section – but in this instance “quartet for three instruments” refers to a piano trio – violin, cello and piano – with two players in piano four hands formation. Evidently it was a common 19th-century grouping, which has since virtually disappeared. Violinist Hector Burgan and cellist Cyrielle Golin are joined by Antoine Mourlas and Mary Olivon sharing the piano bench in delightful multi-movement works by Hermann Berens (1826-1880) and Ferdinand Hummel (1855-1928). (Hummel is not related to Johann Nepomuk Hummel, the only composer of that name of whom I was previously aware.) The only composer represented here whom I did recognize is Felix Mendelssohn, whose Ruy Blas Overture was written in 1839 for a Leipzig production of Victor Hugo’s play of the same name. Fresh and sprightly, Hummel’s Sérénade Im Frühling from 1884 depicts Vienna in sunny springtime, while Berens’ two quartets from the 1860s are in a more classical style, harkening back to the aforementioned Mendelssohn. I was initially concerned that the four hands on the piano would make for muddy textures, hiding the two string instruments, but these well-balanced performances put the lie to that. I’m pleased to have made the acquaintance of these composers, and these fine players, in this great introduction to some little-known repertoire.

We invite submissions. CDs, DVDs and comments should be sent to: DISCoveries, WholeNote Media Inc., The Centre for Social Innovation, 503 – 720 Bathurst St. Toronto ON M5S 2R4.

David Olds, DISCoveries Editor

discoveries@thewholenote.com