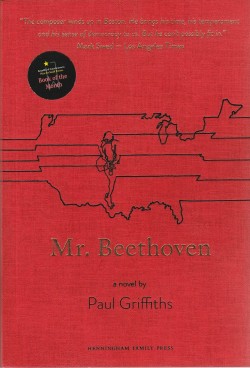

Back in February I mentioned what a joy it was to read the latest from Welsh novelist, musicologist and librettist Paul Griffiths titled Mr. Beethoven. In it, Griffiths imagines Beethoven’s life beyond his purported death in 1827, his visit to Boston and the oratorio he wrote on commission from the Handel and Haydn Society in 1833. I had received an inscribed copy of the small press UK edition (pictured here in red, the small black circle with the gold star declaring it a Republic of Consciousness Prize for Small Presses “Book of the Month”) sent just before Christmas by the author. At his request I deferred writing about the book until the North American publication date this past month. Mr. Beethoven is now available in Canada published by The New York Review of Books (ISBN 9781681375809) and I have taken the occasion to revisit this marvellous novel. In a season when many of my favourite authors have published new books (Richard Powers, Wayne Johnston, Tomson Highway, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Guy Vanderhaeghe, Jonathan Franzen and David Grossman, to name a few) it might have seemed an imposition to have to put them off for a book so recently enjoyed, but I’m pleased to report that, if anything, Mr. Beethoven is even more satisfying the second time around and I know those other books will wait patiently on my To Read shelf.

Back in February I mentioned what a joy it was to read the latest from Welsh novelist, musicologist and librettist Paul Griffiths titled Mr. Beethoven. In it, Griffiths imagines Beethoven’s life beyond his purported death in 1827, his visit to Boston and the oratorio he wrote on commission from the Handel and Haydn Society in 1833. I had received an inscribed copy of the small press UK edition (pictured here in red, the small black circle with the gold star declaring it a Republic of Consciousness Prize for Small Presses “Book of the Month”) sent just before Christmas by the author. At his request I deferred writing about the book until the North American publication date this past month. Mr. Beethoven is now available in Canada published by The New York Review of Books (ISBN 9781681375809) and I have taken the occasion to revisit this marvellous novel. In a season when many of my favourite authors have published new books (Richard Powers, Wayne Johnston, Tomson Highway, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Guy Vanderhaeghe, Jonathan Franzen and David Grossman, to name a few) it might have seemed an imposition to have to put them off for a book so recently enjoyed, but I’m pleased to report that, if anything, Mr. Beethoven is even more satisfying the second time around and I know those other books will wait patiently on my To Read shelf.

As is my wont, I made a point of listening to the music mentioned in the book, at least as far as I was able. The challenge of course was that much of the music discussed, and particularly Job: The Oratorio which is featured so prominently, is imaginary, dating from Beethoven’s fanciful “fourth” (i.e. posthumous) period. Various chamber works are described, including a “Quincy” string quartet, a “Fifths” piano sonata, a clarinet quintet, and even plans for an “Indian Operetta” on indigenous themes using early poetry of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. But there are actual works included as well, such as the antepenultimate – now there’s a word that was new to me – Piano Sonata No.30 in E Major Op.109 and the String Quartet No.15 in A Minor Op.132. But more curiously, other works which would foreshadow the mythical oratorio are mentioned because they would not yet have been performed in Boston at the time, such as the Missa Solemnis Op.123 and the “Choral” Symphony No.9 Op.125 and were therefore unknown to the characters in the novel.

Griffiths has drawn on his skills as a researcher, as well as his imagination and his command of the German language, to produce a hybrid work of pseudo-scholarly biographical/speculative fiction. His conceit that Beethoven, deaf for many years at this point, would have been able to communicate using sign language with the aid of a young amanuensis from Martha’s Vineyard is based on the fact that there was indeed a community there that had developed a system that predated and was later subsumed by American Sign Language. Thankful, the young woman who becomes Beethoven’s voice, interprets for him discretely, leaving out much of the bluster and non-essential verbiage of his interlocutors, enabling him to communicate with those whom he could neither hear nor understand their language. Beethoven’s speech is stilted as a result of this translation process, but Griffiths has ingeniously crafted his dialogue from excerpts of letters and other documents actually written by the composer, as documented in the copious end notes. The characters Beethoven interacts with are fictitious, but also predominantly historical figures, culled from censuses and directories of the time and from the archives of the Handel and Haydn Society. These include the grand landholder John Quincy with whose family the composer spends a summer vacation, and members of the Chickering and Mason households whose descendants would become famous piano manufacturers.

Perhaps most impressive is the description of the mythical oratorio itself, based on the biblical story of Job, and the libretto that is included on facing pages in the final chapters of the book. The details are almost mind-boggling, including notes on orchestration, vocal ranges, staging and interpretation. There is even an authentic notated melody for the boy soprano’s aria, which originated in a sketchbook of Beethoven’s dated 1810.

First published, and first read by me, in 2020 the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth – here are two more words that were new to me (and my spell checker): semiquincentennial and sestercentennial – it seems especially fitting that while reading Mr. Beethoven I immersed myself in the music of that master. Some of it was mentioned in the book, but other works came as a result of new recordings released to coincide with the auspicious year.

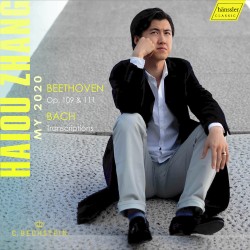

For Op.109 there were numerous choices. Young pianists eager to make their mark with this fabled work included Haiou Zhang and Uriel Pascucci. Zhang’s My 2020 (Hänssler Classic HC20079 naxosdirect.com/search/hc20079) begins with Piano Sonata No.30 followed by the final Sonata No.32 and also includes Bach transcriptions by Feinberg and Lipatti, with two bonus tracks: a cadenza from Beethoven’s fourth piano concerto and the familiar bagatelle Für Elise. In the booklet, Zhang explains the meaning of the disc’s title, referencing COVID-19 and reflecting on having made his Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No.3 debut in Wuhan, and giving masterclasses there, shortly before the outbreak. He goes on to speak about why the Beethoven sonatas have meant so much to him for so long and says that every Sunday morning the Bach transcriptions are part of his “confession.” The performances are equally moving.

For Op.109 there were numerous choices. Young pianists eager to make their mark with this fabled work included Haiou Zhang and Uriel Pascucci. Zhang’s My 2020 (Hänssler Classic HC20079 naxosdirect.com/search/hc20079) begins with Piano Sonata No.30 followed by the final Sonata No.32 and also includes Bach transcriptions by Feinberg and Lipatti, with two bonus tracks: a cadenza from Beethoven’s fourth piano concerto and the familiar bagatelle Für Elise. In the booklet, Zhang explains the meaning of the disc’s title, referencing COVID-19 and reflecting on having made his Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No.3 debut in Wuhan, and giving masterclasses there, shortly before the outbreak. He goes on to speak about why the Beethoven sonatas have meant so much to him for so long and says that every Sunday morning the Bach transcriptions are part of his “confession.” The performances are equally moving.

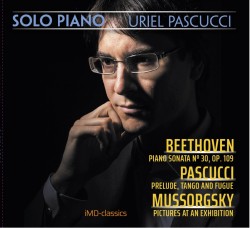

While Zhang has already recorded a number of discs for Hänssler in his young career, Pascucci’s Solo Piano – Beethoven; Pascucci; Mussorgsky (IMD-Classics urielpascucci.com/copy-of-discografía) appears to be his recording debut. Pascucci has chosen to bookend his own Prelude, Tango and Fugue with Beethoven’s Sonata Op.109 and Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. I am a bit discomfited by a couple of abrupt transitions in the third movement of the Beethoven which I attribute to unfortunate edits, but otherwise it is a thoughtful and sensitive performance. The Mussorgsky is powerful and well-balanced, occasional surprises in the use of rubato and syncopation notwithstanding. His own composition shows him at his most comfortable, its contrasting movements each bringing a different mood to the fore. The rhythmic tango, with its pounding chords growing to a near perpetuo mobile ostinato climax is a highlight.

While Zhang has already recorded a number of discs for Hänssler in his young career, Pascucci’s Solo Piano – Beethoven; Pascucci; Mussorgsky (IMD-Classics urielpascucci.com/copy-of-discografía) appears to be his recording debut. Pascucci has chosen to bookend his own Prelude, Tango and Fugue with Beethoven’s Sonata Op.109 and Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. I am a bit discomfited by a couple of abrupt transitions in the third movement of the Beethoven which I attribute to unfortunate edits, but otherwise it is a thoughtful and sensitive performance. The Mussorgsky is powerful and well-balanced, occasional surprises in the use of rubato and syncopation notwithstanding. His own composition shows him at his most comfortable, its contrasting movements each bringing a different mood to the fore. The rhythmic tango, with its pounding chords growing to a near perpetuo mobile ostinato climax is a highlight.

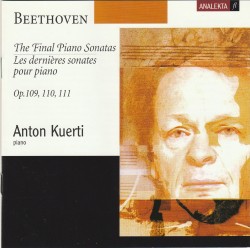

My go-to reference for Beethoven sonatas is Toronto’s own Anton Kuerti. My basement is currently under renovation and the bulk of my vinyl collection is inaccessible at the moment, so I was unable to pull out his original recordings of the entire cycle of 32 on Aquitaine from 1977. Fortunately Kuerti recorded the final five sonatas for Analekta in 2004, released on two CDs: Nos.28, Op.101 and 29, Op.106 (FL 2 3187) and The Final Sonatas, Nos.30, 31 and 32 (FL 2 3182 analekta.com/en). It was to the latter I turned for comparison’s sake, and I must say, to my ears Kuerti just cannot be beat when it comes to this repertoire.

My go-to reference for Beethoven sonatas is Toronto’s own Anton Kuerti. My basement is currently under renovation and the bulk of my vinyl collection is inaccessible at the moment, so I was unable to pull out his original recordings of the entire cycle of 32 on Aquitaine from 1977. Fortunately Kuerti recorded the final five sonatas for Analekta in 2004, released on two CDs: Nos.28, Op.101 and 29, Op.106 (FL 2 3187) and The Final Sonatas, Nos.30, 31 and 32 (FL 2 3182 analekta.com/en). It was to the latter I turned for comparison’s sake, and I must say, to my ears Kuerti just cannot be beat when it comes to this repertoire.

That being said, my piano explorations did not end there. Two mid-career artists also released Beethoven discs recently, Pierre-Laurent Aimard and Jonas Vitaud. Aimard, perhaps best known for his interpretations of contemporary repertoire – especially Messiaen and Ligeti whose Piano Concerto he performed with New Music Concerts here in Toronto early in his career in 1990 – marked the anniversary year with Beethoven: Hammerklavier Sonata and Eroica Variations (PentaTone PTC 5186 724 naxosdirect.com/search/ptc5186724). He is obviously as at home with 200-year-old repertoire as with the music of his own time.

That being said, my piano explorations did not end there. Two mid-career artists also released Beethoven discs recently, Pierre-Laurent Aimard and Jonas Vitaud. Aimard, perhaps best known for his interpretations of contemporary repertoire – especially Messiaen and Ligeti whose Piano Concerto he performed with New Music Concerts here in Toronto early in his career in 1990 – marked the anniversary year with Beethoven: Hammerklavier Sonata and Eroica Variations (PentaTone PTC 5186 724 naxosdirect.com/search/ptc5186724). He is obviously as at home with 200-year-old repertoire as with the music of his own time.

The Eroica Variations date from the year 1802 and Vitaud has chosen to centre his disc around that year in which Beethoven realized he was becoming irreversibly deaf, contemplated suicide and wrote the “Heiligenstadt Testament” to his brothers Carl and Johann. He would overcome his depression and go on to write some of his most powerful works. 1802 – Beethoven Testament de Heiligenstadt (Mirare MIR562 mirare.fr/catalogue) begins with those flamboyant variations and includes Seven Bagatelles Op.33 and Six Variations Op.34 bookending the Piano Sonata Op.31/2 “Tempest” with its undying despair. Vitaud suggests this arc as a depiction of Beethoven’s journey toward hope.

The Eroica Variations date from the year 1802 and Vitaud has chosen to centre his disc around that year in which Beethoven realized he was becoming irreversibly deaf, contemplated suicide and wrote the “Heiligenstadt Testament” to his brothers Carl and Johann. He would overcome his depression and go on to write some of his most powerful works. 1802 – Beethoven Testament de Heiligenstadt (Mirare MIR562 mirare.fr/catalogue) begins with those flamboyant variations and includes Seven Bagatelles Op.33 and Six Variations Op.34 bookending the Piano Sonata Op.31/2 “Tempest” with its undying despair. Vitaud suggests this arc as a depiction of Beethoven’s journey toward hope.

Griffiths mentions that although the first performance in the US of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony was not until 1846, some there might have been aware of the work in Czerny’s piano duet arrangement of 1829. Liszt published solo piano arrangements of the nine symphonies in 1865. As I am writing this, a new two-piano version has just arrived on my desk, Götterfunken (gods’ gleam, or divine spark) featuring the mother-and-daughter team of Eliane Rodrigues and Nina Smeets (navonarecords.com/catalog/nv6382). In the liner notes Rodrigues says; “During the COVID-19 pandemic, I’ve seen so much sadness and pain that I wanted to share a moment of joy, love, and friendship. The only thing that came to mind and heart was Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, in a version for two pianos with my daughter, Nina. My arrangement is not a literal transcription of the orchestral score. Rather, it’s based on what I hear and feel when listening to the orchestral music and Franz Liszt’s arrangement. The main goal was to follow in Beethoven’s footsteps and connect his work to the present day; to achieve what he would have wanted: to unite all people with just one simple melody.” I believe that Rodrigues has succeeded admirably. The semi-improvised sections are not at all jarring, and the result is very satisfying. The overall effect is uplifting, in spite of the absence of Schiller’s anthemic words. Just what we need in these troubled times.

Griffiths mentions that although the first performance in the US of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony was not until 1846, some there might have been aware of the work in Czerny’s piano duet arrangement of 1829. Liszt published solo piano arrangements of the nine symphonies in 1865. As I am writing this, a new two-piano version has just arrived on my desk, Götterfunken (gods’ gleam, or divine spark) featuring the mother-and-daughter team of Eliane Rodrigues and Nina Smeets (navonarecords.com/catalog/nv6382). In the liner notes Rodrigues says; “During the COVID-19 pandemic, I’ve seen so much sadness and pain that I wanted to share a moment of joy, love, and friendship. The only thing that came to mind and heart was Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, in a version for two pianos with my daughter, Nina. My arrangement is not a literal transcription of the orchestral score. Rather, it’s based on what I hear and feel when listening to the orchestral music and Franz Liszt’s arrangement. The main goal was to follow in Beethoven’s footsteps and connect his work to the present day; to achieve what he would have wanted: to unite all people with just one simple melody.” I believe that Rodrigues has succeeded admirably. The semi-improvised sections are not at all jarring, and the result is very satisfying. The overall effect is uplifting, in spite of the absence of Schiller’s anthemic words. Just what we need in these troubled times.

Well that’s a lot of piano indeed, but I’m none the worse for wear. I did add cello to the mix with Yo-Yo Ma and Emmanuel Ax’s Hope Amid Tears – Beethoven Cello Sonatas (sonyclassical.com/releases), a three-CD set that includes the five sonatas and the three sets of variations. I found my personal favourites, Sonata No.3 in A Major, Op.69 and the Variations on Handel’s “Hail the Conquering Hero” to be particularly satisfying. For the record I also listened to the penultimate string quartet, and full orchestral versions of the Ninth Symphony and the Missa Solemnis. For String Quartet No.15 in A Minor Op.132, I chose two recordings from my archives, one by the Tokyo String Quartet recorded when Canadian Peter Oundjian was a member of the group (RCA Red Seal Masters 88691975782), and the other by Canada’s Alcan Quartet (ATMA ACD2 2493). Both are taken from complete cycles of all 16 quartets and I’d be hard pressed to pick a favourite. For Symphony No.9 it was Mariss Jansons conducting a live performance for Bavarian Radio in 2007 whose soloists included Canadian tenor Michael Schade (BRK90015 naxosdirect.com/search/brk90015), and for the Missa Solemnis, it was Leonard Bernstein conducting the New York Philharmonic with the Westminster Choir and soloists Eileen Farrell, Carol Smith, Richard Lewis and Kim Borg from 1961, reissued on Leonard Bernstein The Royal Edition in 1992 (Sony Classical SM2K 47522). I must say I found Borg’s performance put me in mind of the description of the wonderful bass who sang the lead role in the imaginary Job: The Oratorio. It’s a shame it was all in Griffiths’ mind, and of course, in the pages of his marvellous book!

Well that’s a lot of piano indeed, but I’m none the worse for wear. I did add cello to the mix with Yo-Yo Ma and Emmanuel Ax’s Hope Amid Tears – Beethoven Cello Sonatas (sonyclassical.com/releases), a three-CD set that includes the five sonatas and the three sets of variations. I found my personal favourites, Sonata No.3 in A Major, Op.69 and the Variations on Handel’s “Hail the Conquering Hero” to be particularly satisfying. For the record I also listened to the penultimate string quartet, and full orchestral versions of the Ninth Symphony and the Missa Solemnis. For String Quartet No.15 in A Minor Op.132, I chose two recordings from my archives, one by the Tokyo String Quartet recorded when Canadian Peter Oundjian was a member of the group (RCA Red Seal Masters 88691975782), and the other by Canada’s Alcan Quartet (ATMA ACD2 2493). Both are taken from complete cycles of all 16 quartets and I’d be hard pressed to pick a favourite. For Symphony No.9 it was Mariss Jansons conducting a live performance for Bavarian Radio in 2007 whose soloists included Canadian tenor Michael Schade (BRK90015 naxosdirect.com/search/brk90015), and for the Missa Solemnis, it was Leonard Bernstein conducting the New York Philharmonic with the Westminster Choir and soloists Eileen Farrell, Carol Smith, Richard Lewis and Kim Borg from 1961, reissued on Leonard Bernstein The Royal Edition in 1992 (Sony Classical SM2K 47522). I must say I found Borg’s performance put me in mind of the description of the wonderful bass who sang the lead role in the imaginary Job: The Oratorio. It’s a shame it was all in Griffiths’ mind, and of course, in the pages of his marvellous book!

Although Beethoven did not write an oratorio, he did compose one opera, Fidelio. You may read Pamela Margles’ review of the latest recording further on in these pages, and Raul da Gama’s take on the original 1805 version, Leonore, in Volume 26 No.6 of The WholeNote published in March this year.

(Full disclosure, I did not put all of my other reading on hold for the sake of this article. I actually read Grossman’s More Than I Love My Life before starting this column and will read the final 15 pages of Powers’ Bewilderment as soon I finish.)

We invite submissions. CDs, DVDs and comments should be sent to: DISCoveries, WholeNote Media Inc., The Centre for Social Innovation, 503 – 720 Bathurst St. Toronto ON M5S 2R4.

David Olds, DISCoveries Editor

discoveries@thewholenote.com