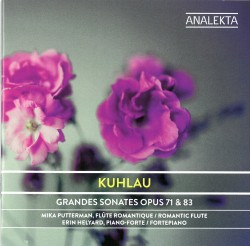

Kuhlau: Grandes Sonates Opus 71 & 83 - Mika Putterman; Erin Helyard

Kuhlau – Grandes Sonates Opus 71 & 83

Kuhlau – Grandes Sonates Opus 71 & 83

Mika Putterman; Erin Helyard

Analekta AN 2 9530 (analekta.com)

Born in Hamburg and later based in Copenhagen, Friedrich Kuhlau (1786-1832) was encountered by my generation mainly as a piano sonatina composer. In his time, however, he succeeded best with music for the flute. Montreal-based specialist Mika Putterman here provides an exemplary demonstration of the Romantic flute’s beauties, in collaboration with Australian fortepianist, conductor and musicologist Erin Helyard. In Kuhlau’s Grand Sonata for Fortepiano and Flute Obbligato, Op. 71 in E Minor (1825) and the similarly named Op. 83, No. 1 in G Major (1827) the duo also practises tempo modification, i.e. speeding up or slowing down beyond what is specified in the score. It takes time to get used to this, as is usual with unfamiliar historically informed performance practices.

I particularly enjoyed the E-minor sonata for its instrumental interplay, florid display and melodic attractiveness. Putterman plays with pure, non-vibrato tone that can be sweet or sad, and is very affecting in the slow movement’s melody. Helyard is a confident fortepianist, though sometimes his solid chords are over-prominent. Both are excellent technically and their ensemble is tight. The G-major sonata’s middle movement is a set of variations, where each player impresses with the ability to play fast passages with convincing expressive touches. Of the outer movements I preferred the first, and must mention Helyard’s fluent double-thirds here and elsewhere. Along with specialists, I think this disc would appeal to those open to new challenges for performers and listeners alike.