Domenico Scarlatti; Muzio Clementi – Keyboard Sonatas

Domenico Scarlatti; Muzio Clementi – Keyboard Sonatas

John McCabe

Divine Art dda 21231 (divineartrecords.com)

The erudite composer and pianist John McCabe left his mark on British music-making in the 20th century. His gifts as interpreter at the keyboard were very much equal to his abilities as composer. Discographic focus for the majority of his life centred upon neglected composers of old: Haydn, Clementi and Nielsen, among others. A recent reissue of two LPs that McCabe recorded in the early 1980s is a welcome one, pairing well-loved sonatas by Domenico Scarlatti with somewhat obscure works by the Italian-born English composer, pianist, pedagogue, conductor, music publisher, editor and piano manufacturer(!) Muzio Clementi.

McCabe brings a muscular, cerebral approach to these pieces. One immediately detects a scrupulous composer behind the studio microphones, carefully etching formal structures for the benefit of the listener with accuracy and intellectual rigour. It is evident that McCabe delights in this piano music yet never indulges, electing for efficient lines and tasteful embellishment, reflective of both style and substance.

Among the various highlights of Disc Two (Clementi) is the Sonata in G Minor, Op.50 No.3, subtitled “Didone Abbandonata” and composed in 1821. Expressive and probing, this music is liberated from the confines of continental neoclassicism, at once mournful and forlorn in prophetic anticipation of 19th-century music yet unwrit. From the last of his opuses for piano, Clementi marks the final movement of this sonata Allegro agitato e con disperazione. Such qualifiers were few and far between, even in 1821!

Adam Sherkin

Haydn Piano Sonatas Vol.2

Haydn Piano Sonatas Vol.2

John O’Conor

Steinway & Sons 30110 (steinway.com)

Celebrated for his characterful, refined interpretations of Beethoven, Schubert and – rather notably – John Ireland, Irish pianist John O’Conor has recently ventured into the 52 sonata-strong catalogue of Franz Joseph Haydn. The second in a projected series of such recordings with Steinway & Sons, this most recent release generally features late sonatas, varied in their formal structures yet irresistible in their innovations. O’Conor brings his customary warmth and tasteful approach to these classical essays: quirky, unexpected works at a good distance from the tautly balanced sonatas of Mozart and Schubert.

Haydn’s experiments in the genre offer a wide spectrum of musical personality. They brush boisterously with folk idioms of the 18th century, skewing phrasing and lyrical gesture in a ribald quest of mirth and merriment. Their slightly rough-and-tumble profile is not always captured by O’Conor. He appears to prize refined voicing and sculpted colour over a bit of pianistic fun. (Once in a while however, he does let himself loose amongst this music’s rustic urgings.) Despite the craft and polish, one detects a faint lack of familiarity with these works; figures and flourishes sound half-hearted, almost glossed over.

It is in the slow movements on this record where O’Conor sounds most at home. He brings a sincerity to Haydn’s melodic lines born of an intimate, semplice mode of expression. O’Conor’s ear for colouristic subtlety delivers harmonic poise and vocal nuance, begetting interpretations that would surely have made the old Austrian composer smile.

Adam Sherkin

Beethoven – The Piano Concertos

Ronald Brautigam; Die Kolner Akademie; Michael Alexander Willens

BIS BIS-2274 SACD (bis.se)

Beethoven – Piano Concertos 0-5

Mari Kodama; Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin; Kent Nagano

Berlin Classics 0301304BC (naxosdirect.com)

The arrival of 2020 commences a year of celebration for classical music presenters and aficionados across the globe, who will celebrate the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth with innumerable concerts featuring the master’s greatest works. In advance of this significant anniversary, two recordings of Beethoven’s complete piano concertos were released late last year: one features the husband and wife duo of pianist Mari Kodama and conductor Kent Nagano; while the other presents fortepianist Ronald Brautigam, who is no stranger to Toronto, having performed with Tafelmusik at Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre in 2010.

Although these collections contain nearly identical musical contents (in addition to the standard five concertos, the Kodama/Nagano release includes the Rondo in B-flat, Eroica Variations, Triple Concerto, and the reconstructed Piano Concerto “0”), the end results are strikingly similar yet could also not be more different. Both recordings are of the highest musical quality, starting with the sound of the orchestras. Each ensemble is sleek and streamlined, with an overall transparency of sound that is now expected from both modern and period orchestras alike; no longer is the Beethoven standard one of deep, heavy, vibrato-filled tone, but it is rather characterized by its agility and precision, as players and conductors attempt to apply historical principles to their modern instruments and ensembles.

Both discs feature thoughtful and precise interpretations that are themselves similar in many ways. Beethoven intended to be quite clear about his expected tempi and dynamics and years of scholarly investigation and research have resulted in scores that are more faithful to the composer’s wishes and intentions than at any other time in post-Beethoven history. We should, therefore, expect overall consistency between slightly differing interpretations, as we discover with these two discs.

What is far more worthwhile to uncover are the differences between these two Beethovenian essays, the most apparent of which is the choice of keyboard instrument. Kodama, as one might expect, plays a grand piano and has the backing of a full symphony orchestra, the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, to provide balance. This is a standard modern approach in which “loud” is loud and “soft” is soft, and we hear this on disc as we would in a concert hall.

Brautigam, however, plays a fortepiano, which began a period of steady evolution in Beethoven’s time, culminating in the late 19th century with the modern grand. It is perhaps easiest to think of the fortepiano as a harpsichord-piano hybrid, for it bridged the gap between these two instruments. The sound is closer to that of a modern piano due to the strings being struck rather than plucked, but its lack of size and power results in a timbre that is far more subdued and subtle than any modern piano. Brautigam’s fortepiano is, therefore, a perfect match for the Köln Academy Orchestra, a period instrument ensemble, whose own instruments are significantly less strident than their modern counterparts.

If Nagano and Kodama’s concertos are built for the concert hall, Brautigam’s are conceived for the chamber hall or theatre. While this decrease in overall volume is not perceptible over a mastered audio disc, it is noticeable that the “loud” is not as loud and the “soft” not as soft, simply due to the fortepiano’s reduced size and inherent limitations; it increases one’s desire to focus as it cuts out the dynamic extremities of the modern piano and shifts one’s attention to subtle changes in volume and articulation.

Choosing or recommending one of these recordings over the other is an impossible task. When viewed through the widest lens, both are superb studies featuring exquisite playing and impeccable musicianship, and the differences become almost secondary. Perhaps the best approach is to acquire both and absorb the slight stylistic differences produced by the instrumental choices, especially if one is familiar primarily with either modern or historical performances. In the end, these discs demonstrate one irrefutable truth: after 250 years, Beethoven’s music is still vibrant and thrilling, even to those who have heard these works many times before.

Matthew Whitfield

Piano Works by Clara and Robert Schumann

Piano Works by Clara and Robert Schumann

Margarita Hohenrieter

Solo Musica SM312 (naxosdirect.com)

I am quite a fan of pianist Margarita Höhenrieder, particularly playing the Schumanns. However, my immediate and continued focus of attention on first hearing this disc was not on the repertoire, not on the pianist, but on the piano. Attending to its authenticity, Höhenrieder tells the story of how this recording came to be. “After just a few notes on the exceptionally fine Pleyel grand piano in Kellinghausen, north of Hamburg, in a collection of Eric Feller’s, I found myself plunged into a different century. The pianoforte was built in Paris in about 1855 and professionally restored using historical materials and methods. It is absolutely uniform with the instrument that Chopin possessed and of typically French elegance – in sound as well as in appearance. It reflects the soul of the Romantic era. Apart from that, it offers an authentic testimony to the sound of the instruments that Fryderyk Chopin and Robert and Clara Schumann played.”

The technique then required to play this piano differs from today’s. The sound from this old instrument is finely articulate and does not produce the same overtones and resonance, nor the volume. Such instruments were expected to be heard in a room or salon having only a fraction of the volume of today’s concert halls. Moreover, a suitable room for a perfect recording is certainly essential. In this case a private salon in Zug, Switzerland from January 16 to 18, 2019 was just that.

Our pianist was right; what we hear here takes to us back to a different century. I hope that Solo Musica plans to record Chopin with Höhenrieder playing the same instrument. That would be something to hear.

Bruce Surtees

Chopin – Late Masterpieces

Chopin – Late Masterpieces

Sandro Russo

Steinway & Sons 30125 (naxosdirect.com)

Italian pianist Sandro Russo revives the elegance and grandeur of the 19th-century piano tradition in this recording of late Chopin works. Having previously recorded several major piano works from the Romantic repertoire (as well as those of lesser-known composers), on this album Russo highlights every aspect of Chopin’s inner world. A selection of pieces that includes both intimate forms such as the mazurka and berceuse and the monumental Third Piano Sonata, this album feels like a personal memento. Noble forces are at work here, generating the sound aesthetics of beauty and adroit virtuosity, a combination that is well suited to Chopin’s music and is the essence of Russo’s artistic expression.

Three mazurkas on this album are a perfect example of Chopin’s mastery of expressing the grand gestures in small-scale works. Mazurka in C Minor Op.56 in particular is a microcosm of understated emotions of melancholy and surrender, yet it contains innovative musical language that at times seems different than anything Chopin had written previously. As a contrast, the Sonata in B Minor Op.58 is as big as it can get. This complex piece is a macrocosm of amplified emotions, an unrestricted cascade of brilliant phrases that command attention and challenge the performer both musically and technically. Sandro Russo is immaculate in both, bringing a fresh approach while keeping with the tradition of the grandiose Romantic era.

Ivana Popovic

Alkan – Symphony for Solo Piano; Concerto for Solo Piano

Alkan – Symphony for Solo Piano; Concerto for Solo Piano

Paul Wee

BIS BIS-2465 SACD (naxosdirect.com)

Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813-88) was a true maverick amongst the great French musicians of the mid-19th century. A child prodigy from a family of exceptionally talented Jewish musicians (the Morhanges), Valentin, using his father’s given name of Alkan as his surname, performed brilliantly in fashionable Parisian salons beginning in 1826, a practice that soon attracted an invasion of foreign pianists including Liszt and Chopin. In 1838, having unwittingly fathered an illegitimate son, he withdrew from the concert circuit for some time, raising his child and devoting himself to composition. He briefly returned to the stage before becoming a total recluse for some 20 years, involving himself with creating a now lost French translation of the Bible from Hebrew sources and publishing numerous compositions.

Alkan’s legacy was largely neglected until a revival of interest in the 1960s brought forth a flood of recordings. Among the five Alkan discs issued in 2019 we have this release by the admirable pianist and barrister Paul Wee, who delivers insightful and riveting accounts of the gargantuan Symphony and Concerto for Solo Piano that form the bulk of Alkan’s Douze études dans tous les tons mineurs Op.39. This is music of extraordinary energy whose obsessive rhythmic profile sweeps all before it with a Beethovenian grandeur. Alkan’s daunting technical demands are never merely gaudy examples of pianistic prestidigitation; they are rather an integral architectural component of his unique and strangely compelling voice.

Daniel Foley

Ravel – Jeux de miroirs

Ravel – Jeux de miroirs

Javier Perianes; Orchestre de Paris; Josep Pons

Harmonia mundi HMM902326 (harmoniamundi.com)

As the clever title indicates this most enjoyable, adventurous undertaking by harmonia mundi sets the piano works of Ravel side by side with their orchestral versions as if they were mirrored. Coincidentally one set of Ravel’s piano works is entitled Miroirs from which we hear the fourth piece Alborada del grazioso, inspired by Spain, one of his main influences.

Ravel was a tremendous orchestrator and he orchestrated many of his own works plus the works of others. Here we can see why and the pianist chosen is Javier Perianes, a young Spanish pianist who has already conquered many of the world’s concert stages and worked with some of the greatest conductors. An artist with unbounded imagination and a special affinity towards French impressionisme, he has beautiful touch and unlimited technical skill.

The main work is Le Tombeau de Couperin, Ravel’s highly personal tribute to 18th-century French Baroque composers, Couperin, Rameau and Lully. The set of six pieces first appears in the piano version and my favourites are Forlane with an infectious, incessant and very catchy melody that’s almost hypnotic, Rigaudon an explosive, high-spirited French courtly dance and the final Toccata where the pianist literally plays up a storm. Later on come the orchestral versions of these and we will be surprised how much additional richness a brilliant orchestration can produce.

The disc opens with the orchestral version of Alborada del grazioso followed by the original solo piano Tombeau. Cleverly set in between the mirrored versions of these pieces is an absolutely astounding reading of the very popular, forward-looking and jazzy Concerto in G characterized by “subtle playing of Javier Perianes and the refined sonorities of the Orchestre de Paris, conducted by Josep Pons.”

I’ve listened to this disc over and over again and hopefully so will you.

Janos Gardonyi

The Etudes Project Volume One – ICEBERG

The Etudes Project Volume One – ICEBERG

Jenny Lin

Sono Luminus DSL-92236 (sonoluminus.com)

Another marvel of a record hits our ears from the enviable, masterful pianist – a paragon of the 21st-century keyboard – Jenny Lin. Lin has long been fascinated with the “intricate history of piano études,” examining the current state of the genre and charting its near 300-year lineage. She has themed this journey and its transpiring narratives, The Etudes Project.

Aligning with composers of ICEBERG New Music, Lin gave its ten members absolute freedom of style and pianistic approach when crafting new etudes for her. The exceptional results were not only premiered by Lin this past October in New York but also published by NewMusicShelf in complete score, released on the same day.

In addition to her Herculean playing, the fearless pianist brings curatorial prowess to bear in pairing each new etude with an existing work from the canon. Seminal music by Ligeti, Chin, Glass, Crawford Seeger, Debussy, Scriabin and – of course – Chopin is featured. Accordingly, the record frames ten diptychs, (old meeting new), as it delivers a novel focus and perspective. The staggering array of textures and colouristic effects – not to mention the technical demands – here demonstrate Lin’s utter virtuosity at the piano, founded upon tireless application of intellect, study, two ultra-keen ears and a generous musical heart worthy of any audience’s patronage and awe.

Have a listen to this disc and then have another; purchase a copy of the score. The Etudes Project will repay you manifestly.

Adam Sherkin

Aubade – Music by Auguste Descarries

Aubade – Music by Auguste Descarries

Janelle Fung

Centrediscs CMCCD 27519 (cmccanada.org)

The rarely performed and underrepresented Quebec composer, Auguste Descarries (1896-1958) is the focal point of a new solo disc by ambitious young pianist Janelle Fung. The composer’s piano sonata was only just given its premiere in 2017, 64 years after its composition! Fung has retrieved six of Descarries’ keyboard works from the proverbial dustbin of musical history, offering forthright and impressive attention to every last note on this recording.

Descarries was an industrious pianist/composer, penning the Rhapsodie Canadienne for piano and orchestra in 1936. His style seems indebted to the Russian and French schools, further enhanced by an apparent meeting with Sergei Rachmaninoff and close relationship with Nicolai Medtner, (carried out during the 1920s). In the end, Descarries lived his latter days in Montreal, the city of his birth.

Opening with the poetic, fantastical Serenitas, this album lures us into a seemingly familiar yet recondite soundworld. Romantic gesture and pastoral vignette meld in such offbeat North American pieces from a bygone age. Fung manoeuvres every turn and lyrical leap with virtuosic aplomb. Her eager, communicative style reveals a pianistic maturity. Such assuredness is most remarkable and one can only muse about Fung’s next projects and newfound devotions to unduly neglected keyboard works by Canadian composers.

The sound quality itself is bright and vivid, the record expertly produced. The team behind the project runs an impressive list, complementing the fine liner notes and poignant artist statement from Fung.

Adam Sherkin

Poul Ruders Edition Vol.15 – Piano Concerto No.3; Cembal d’Amore, Second Book; Kafkapriccio

Poul Ruders Edition Vol.15 – Piano Concerto No.3; Cembal d’Amore, Second Book; Kafkapriccio

Various Artists

Bridge Records 9531 (bridgerecords.com)

Illustrious Danish composer Poul Ruders seems to have been blessed with abiding compositional fluency. He pens work after work in a consistent outpouring of top-notch pieces, adding to a lifelong musical catalogue that is both communicative and compelling. A most recent album featuring his music for keyboard is no exception.

With a rather eclectic mix of concerto, harpsichord/piano duo and operatic paraphrase, this record begins with Ruders’ newest piano concerto – the third – written in 2014. Pianist Anne-Marie McDermott tackles this demanding, mesmerizing single movement with her habitual panache. The dizzying acrobatics sound only a sheer delight under her steadfast command. Subtitled “Paganini Variations,” Ruders here takes a timeworn tune – long pillaged and mined by others – turning music afresh. Variation after variation offer up surprises, highlighting the mark of a true craftsman still at the height of his powers.

Cembal d’Amore, Second Book (a duo for piano and harpsichord) from 2007 is perhaps more novel in its conception, at once celebrating the disparity and similarity between two keyboard instruments. Quattro Mani masters the blend and kinship of the diverse sound pallets throughout the eight movements. With the help of Ruders’ quicksilver, pugnacious score, this performance reaches an impressive benchmark, refined and exacting in its artistry. The work was commissioned by New York’s Speculum Musicae; it is feasible that not since Elliott Carter’s Double Concerto for piano and harpsichord (1961), has this unique instrumental combination been employed so successfully.

Adam Sherkin

Anna Höstman – Harbour

Anna Höstman – Harbour

Cheryl Duvall

Redshift Records TK473 (redshiftrecords.org)

Composer Anna Höstman and Toronto-based pianist Cheryl Duvall collaborate effectively on Harbour. Born in Bella Coola, British Columbia, now teaching at the University of Victoria, Höstman has earned significant residencies and performances. Her sense of the Pacific coastal environment is congenial, at least to my Vancouver-raised sensibilities. Also, I applaud her composing of the short, slow piano-left-hand piece, late winter (2019), for a musician whose right hand was temporarily disabled, having this condition myself and having done musical work with people with disabilities. In this composition, two recurring but long-separated high tones sound over a texture of arpeggiated chords. The note A becomes important, while one high E now recurs. Gradual change, peaceful though somewhat uneasy moods, and expertise with piano writing and sonority seem characteristic for this composer.

There is much variety among other works: allemande (2013) begins sparely, reminding us of the voice. Subtle textural changes begin with two- or three-note sonorities, followed by register shifts and larger clusters. Harbour (2015) is full and more turbulent yet clearly layered – Duvall’s refined but powerful pianism brings sonorous appeal throughout this longer work. If we lose our way isn’t it enough to become attentive to sounds, allowing the piece to grow on us? darkness … pines (2010) begins with complex chords; later a few triads glint through. Yellow Bird (2019) moves fitfully, topped with high chirping; Adagio (2019) pulsates slowly. A disc to be experienced – gradually.

Roger Knox

Across the veiled distances – Music by Hope Lee

Across the veiled distances – Music by Hope Lee

Yumiko Meguri; Stefan Hussong

Centrediscs CMCCD 27219 (cmccanada.org)

Canadian composer Hope Lee’s unique music with its self-described ancient Chinese influences is heard in four piano compositions and one piano/accordion duet from four decades (1979-2017).

Brilliant Japanese pianist Yumiko Meguri performs Lee’s technically challenging, dramatic works perfectly. The four-section Across the veiled distances (1996) is part of a larger multimedia project inspired by a Marguerite Yourcenar short story based on Chinese legend. Played as one movement, the loud chordal opening leads to mystical musical conversations between the hands, with ringing string resonances, trills and contrasting driving and reflective repeated notes. The more atonal new-music-sounding Dindle (1979) opens with very soft percussive banging, followed by contrasting dynamic chords, pitches and single lines separated by silent spaces. These same ideas resurface in Lee’s later piano work in o som do desassossego (2015).

In Entends le passé qui march (1992), recorded sound files add unique sound and exact time dimensions to the intense live piano part. In 2017’s Imaginary Garden V. (renewed at every glance) – part of a seven-section chamber piece for unusual instruments – superstar German free bass accordionist Stefan Hussong joins Meguri. Effective use of each instrument’s inherent qualities can be heard in such soundscapes as a piano percussive marching riff against long-held accordion tones, accordion held-note swells and vibratos against piano high note lines, accordion air button-created whispers and simultaneous two-instrument high pitches.

Across the veiled distances provides a great, in-depth cross-section of Lee’s piano works.

Tiina Kiik

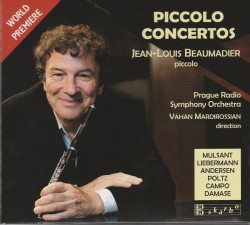

Piccolo Concertos

Piccolo Concertos