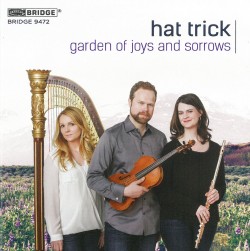

Garden of Joys and Sorrows - Hat Trick

Garden of Joys and Sorrows

Garden of Joys and Sorrows

Hat Trick

Bridge Records 9472 bridgerecords.com

Review

This CD features the first recording of Debussy’s Sonata for Flute, Viola, and Harp (1915) using the new Carl Fischer edition, incorporating original score details differing from the initial publication. The opening Pastorale is somewhat reminiscent of Debussy’s piano prelude The Girl with the Flaxen Hair, yet more mysterious. The New York-based trio Hat Trick plays it with suggestions of light and colour, but without the languorous drooping at cadences I have heard sometimes. In the Interlude following, Hat Trick again resists over-interpretation, letting the tonal feast proceed unhindered. Articulation and ensemble are precise in their spirited Finale.

A conventional Terzettino (1905) by Théodore Dubois was the first piece for flute, viola, and harp, given here with appealing French sentiment. Uruguayan-born Miguel del Aguila’s commissioned work Submerged (2013) here receives its CD premiere. Hat Trick brings excitement and commitment to its dance rhythms and under-the-sea imagery. The group plays Toro Takemitsu’s And then I knew ’twas Wind (1992) with sensitivity to evocative contemporary timbres and textures, the work’s main attractions. I find the tonal material much derived from Messiaen’s scales, though. Sofia Gubaidulina`s 1980 Garten von Freuden und Traurigkeiten (Garden of Joys and Sorrows) is the lengthiest work. Its extended exploration of harmonics, glissandi, percussive harp and many other effects is realized here with maximal facility. Altogether this is a stellar production by Hat Trick – April Clayton, flute; David Wallace, viola; and Kristi Shade, harp – who indeed make every shot count.