The Blurring of Time at 21C

Keeping apace of new music events in the city is like a never-ending discovery of new ideas, initiatives and opportunities to expand one’s horizons on both the local and international scenes. The Royal Conservatory’s annual 21C Music Festival, running from May 23 to 27, provides an opportunity to experience all this within a five-day span, with eight concerts and 37 premieres. The Kronos Quartet, along with composer and multi-instrumental performer Jherek Bischoff, will open the festival, followed by concerts featuring a number of different international and national pianists, including Anthony de Mare with his special project Liaisons: Re-Imagining Sondheim From the Piano, Sri Lankan-Canadian composer and pianist Dinuk Wijeratne performing with Syrian composer and clarinetist Kinan Azmeh, and the French sibling pianists Katia and Marielle Labèque.

As is customary for 21C, one of their concerts is a co-presentation with an established Toronto new music presenter – in this case, New Music Concerts, who will bring a Claude Vivier-inspired program to Mazzoleni Hall on May 27. This year, however, a second co-presentation also caught my eye: Grammy Award-winning vocal ensemble Vox Clamantis with Maarja Nuut & HH, presented on May 26 in collaboration with Estonian Music Week, running concurrently in the city from May 24 to 29.

The Estonian Music Week co-presentation is one of two concerts at 21C that combine music by contemporary composers with music of the past – thus creating a blurring of time, as it were. Vox Clamantis will offer both Gregorian chant music alongside contemporary works by primarily Estonian composers – while in another 21C show on May 25, pianist Simone Dinnerstein and the A Far Cry chamber orchestra will combine two works by J.S. Bach and two by Philip Glass.

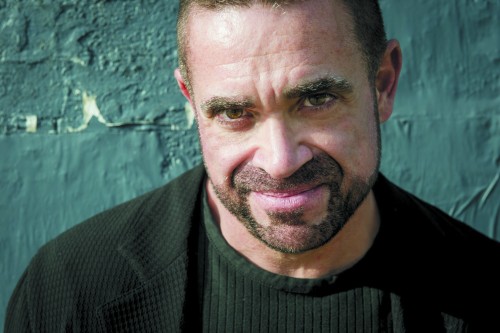

I had an opportunity to speak with Jaan-Eik Tulve, the conductor of Vox Clamantis, about the ensemble, the connections between Gregorian chant and contemporary music, and the legendary singing tradition in Estonia. Vox Clamantis was formed 20 years ago by Tulve as a way to continue singing the Gregorian chant he had studied in Paris in the 1990s. However, it quickly expanded into an ensemble that embraced the music of contemporary Estonian composers, who were keen to write music for them. One of the key reasons for this desire to compose for Vox Clamantis, Tulve told me, “was because they found that our musicality, phrasing and voices are different from classical singers. Even though Gregorian chant is the basis for classical music, the differences are that it is unmetered and monophonic music, so you must pay close attention to phrasing and listening to each other.”

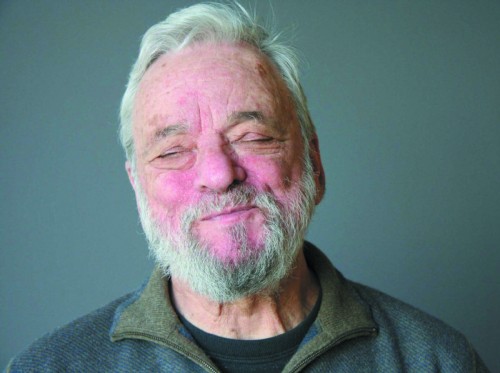

One of the composers the ensemble has a very close working relationship with is the esteemed Estonian composer Arvo Pärt. Back in 1980, Pärt was forced to leave Estonia, which was part of the USSR at the time, in order to have his creative freedom. He lived in Berlin for 30 years, only returning to Estonia in the late 1990s after the country regained its independence. A strong relationship between Pärt and Vox Clamantis was quickly established, strengthened by the fact that Pärt had studied Gregorian chant when he was young. “We found a lot of similarities in our musical expressions and understandings of music, and little by little we sang more and more music that he wrote for us. He also often comes to us with new compositions while he is working on them so he can hear what they sound like,” Tulve said. The program at the 21C Festival will include five pieces by Pärt, all of which are on The Deer’s Cry CD, an album fully dedicated to performances of Pärt’s music by Vox Clamantis. As well, one of the repertoire programs that the ensemble regularly performs is comprised of a mixture of Pärt’s music with Gregorian music, a program designed by both Tulve and Pärt.

One of the composers the ensemble has a very close working relationship with is the esteemed Estonian composer Arvo Pärt. Back in 1980, Pärt was forced to leave Estonia, which was part of the USSR at the time, in order to have his creative freedom. He lived in Berlin for 30 years, only returning to Estonia in the late 1990s after the country regained its independence. A strong relationship between Pärt and Vox Clamantis was quickly established, strengthened by the fact that Pärt had studied Gregorian chant when he was young. “We found a lot of similarities in our musical expressions and understandings of music, and little by little we sang more and more music that he wrote for us. He also often comes to us with new compositions while he is working on them so he can hear what they sound like,” Tulve said. The program at the 21C Festival will include five pieces by Pärt, all of which are on The Deer’s Cry CD, an album fully dedicated to performances of Pärt’s music by Vox Clamantis. As well, one of the repertoire programs that the ensemble regularly performs is comprised of a mixture of Pärt’s music with Gregorian music, a program designed by both Tulve and Pärt.

Other contemporary composers whose works will be on Vox Clamantis’ 21C program include the music of Helena Tulve, Jaan-Eik’s wife, who also studied Gregorian chant along with contemporary composition. “It’s a very short but concentrated monophonic piece which is quite different from most of her other instrumental compositions,” Tulve said. It will be paired with Ave Maria by Tõnis Kaumann, who is also a singer in the ensemble. And finally, a work by American composer David Lang will round out the concert, demonstrating Lang’s ability to write in a wide range of styles. When I asked Tulve about the connection between the ensemble and Lang’s musical language, he remarked that Lang’s music “was perfect for our ensemble as it is quite close to our musicality. It’s minimalist music, and we find minimalism in Pärt’s music, Gregorian chant and Lang’s music. Minimalism is the one common point.”

I concluded my conversation with Tulve by asking him to speak about the relationship between singing and the Estonian national identity. In what’s known as the Estonian Age of Awakening, which began in the 1850s and ended in 1918 with the declaration of the Republic of Estonia, the Estonian Song Festival was established in 1869. It is one of the largest amateur choral events in the world, held every five years, bringing together around 30,000 singers to perform the same repertoire for an audience of up to 80,000. “This festival was very important during the Soviet occupation” Tulve told me, “and helped Estonians survive this period by strengthening their own national identity. To preserve this strong link between singing and the Estonian identity, every child learns to sing in choirs at school, and the singing is at a very high level throughout the country with many good amateur choirs.”

Two other Estonian performers will also take to the stage that same evening – Maarja Nuut, performing on vocals, violin and electronics, along with Hendrik Kaljujärv on electronics. For the evening finale, the choir and these two young experimental performers will come together with a work performed by Vox Clamantis with improvisations by Nuut and Kaljujärv.

Simone Dinnerstein with A Far Cry

One of the pianists the 21C Festival is programming is Brooklyn-based Simone Dinnerstein, who burst onto the international scene with her self-produced recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations in 2007. Since that time, she has performed internationally, with repertoire spanning from Baroque to select 21st-century works especially composed for her. Recently, she entered into a creative collaboration with composer Philip Glass, whose Piano Concerto No. 3 for piano and strings will receive its Canadian premiere at 21C along with pieces by J.S. Bach and Glass’ Symphony No.3. The concerto was a co-commission from a consortium of 12 orchestras; it was premiered in Boston in 2017 with string orchestra A Far Cry.

In my recent phone interview with her, Dinnerstein spoke about how this came about. The idea arose in 2014 when both artists discovered that they had a mutual interest in the music of Bach. Glass was interested in writing a work for her and Dinnerstein proposed that it be a concerto for piano and string orchestra. “I thought it would be interesting if the performance of the piece was paired with a Bach concerto,” she said. “All of Bach’s keyboard concertos are for keyboard and string orchestra, and there haven’t been many pieces written for that combination since Bach’s time. Glass liked the idea and from there, along with A Far Cry, we all decided it would be interesting to create a whole program with music by Bach and Glass.” At the May 25 concert, the first half includes Glass’ Symphony No. 3 followed by Bach’s Keyboard Concerto in G Minor BWV1058, and in the second half, Bach’s Orchestral Suite No. 2 in B Minor will be followed by Glass’ new Piano Concerto. And just in time for the festival, the two keyboard concertos on the program will be available on a CD titled Circles.

In my recent phone interview with her, Dinnerstein spoke about how this came about. The idea arose in 2014 when both artists discovered that they had a mutual interest in the music of Bach. Glass was interested in writing a work for her and Dinnerstein proposed that it be a concerto for piano and string orchestra. “I thought it would be interesting if the performance of the piece was paired with a Bach concerto,” she said. “All of Bach’s keyboard concertos are for keyboard and string orchestra, and there haven’t been many pieces written for that combination since Bach’s time. Glass liked the idea and from there, along with A Far Cry, we all decided it would be interesting to create a whole program with music by Bach and Glass.” At the May 25 concert, the first half includes Glass’ Symphony No. 3 followed by Bach’s Keyboard Concerto in G Minor BWV1058, and in the second half, Bach’s Orchestral Suite No. 2 in B Minor will be followed by Glass’ new Piano Concerto. And just in time for the festival, the two keyboard concertos on the program will be available on a CD titled Circles.

Glass’ concerto is written in three movements, with some parts more flowing and others quite dynamic. Dinnerstein said that in the second movement, some parts remind her of rock music in terms of sonority and rhythm. “At times the orchestra almost sounds like one of those 1970s synthesizers and it’s a really amazing sound. The third movement is definitely what I call transcendental music.”

In a an accidental but striking instance of synchronicity between 21C and Estonian Music Week, this third movement is dedicated to Arvo Pärt. “I can see why he dedicated it to Pärt,” Dinnerstein commented, “because there is a stillness to it that is present in a lot of Pärt’s music. But to me, it still sounds very much like Philip Glass. It’s a very slow-paced movement and is extremely difficult to rehearse because you need to be an active listener all the time. Everybody in the orchestra and the pianist have to be really aware of each other and of the music moment by moment, which takes a great deal of focus. I’ve now played this with a number of orchestras and one of the things that is wonderful about playing it with A Far Cry is they are an ensemble that really spends a lot of time listening to each other since they have no conductor. It’s part of their artistic personality to be able to respond to each other in a very instantaneous way, so we’ve tried different things with that movement. I might suddenly change something I’m doing and they have to respond to it without having a plan, so it’s much more improvisatory. That kind of thing is very hard to do with a larger orchestra and a conductor, but with them, it’s really possible.”

Dinnerstein went on to describe the commonalities between the music of Glass and Bach. “Both of their writing deals a lot with sequences of patterns and they have a common interest in the larger architecture of a piece. As well, they have written relatively very little regarding the interpretation of a performance. Their use of tempo, articulation and dynamic markings is quite bare, so that leaves a great deal up to the interpreter to try and delve into the music and see what the music is saying to them. I love that about those composers. As a result, when you hear different people play their music, it can sound wildly different.”

As for commonalities between Baroque and contemporary music, Dinnerstein commented: “I’ve always thought there’s a stronger connection there than between Romantic music and contemporary music. There’s a kind of abstraction to both Baroque and contemporary, and if you listen to Chopin for example, it feels very much of its time. You’re very aware of Chopin the artist. With Bach and Glass, the expression is less tied to the composers themselves – I don’t feel a sense of them as people. Rather, I feel that whoever is playing their music can bring out something quite different. The personality of the composer feels less dominant and there is a wider spectrum that lies within the music itself.”

What is striking about both these concerts I’ve highlighted here is the way contemporary music is linked with the sensibilities of both medieval Gregorian chant and Baroque music. It will definitely make for some fascinating listening – and an opportunity to experience music in all its timelessness.

Wendalyn Bartley is a Toronto-based composer and electro-vocal sound artist. sounddreaming@gmail.com.