The Dreaded Cough

Welcome to this double edition of Choral Scene! By the time you get your hands on this magazine the holiday season will be well under way. Carols will get in your ear, festive sounds will echo out and bells will be a-ringing throughout the region. I hope you’ve got your concert tickets in hand. If not, hurry up and reserve your place in these amazing concerts before you’re disappointed. Balancing out the holiday season, I’m also going to highlight some interesting performances you should check out in the choral world into the new year. We’ll be back in February, just in time for Chinese New Year on February 16, 2018 – the Year of the Dog! But I’m going to highlight a few performances well beyond the date that you might want to circle in one of the seasonal calendars you will doubtless be acquiring in the coming weeks.

Stage Coughs

But first, from a chorister’s perspective, some thoughts on the dreaded cough and wintry illness for singers!

In November’s WholeNote, Vivien Fellegi wrote about major injuries and musicians and noted that 84 percent of musicians will have to deal with a significant injury affecting their ability to make music. If you ask any vocalist to name their performance terror, it usually involves being sick around performance time. Four years ago, during an especially illness-fraught Messiah run at the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, the flu and cold hit our soprano and bass soloists. Eventually, a sub for the bass needed to be called in to finish the run. Members of the choir were hit as well. Good performers put on a good show even when adverse conditions exist, but even then, there’s only so much one can do when your body is under bacterial or viral attack.

This past October, I got a pretty bad viral throat infection. It cleared, but the residual cough and throat irritation continued for a few weeks. The result was a lot of rehearsals spent sitting in the back, humming along as we began going through Suzanne Steele and Jeffrey Ryan’s Afghanistan: Requiem for a Generation. My voice returned in time for the Remembrance Day performances but there was coughing during the performance I just couldn’t control. A persistently irritated throat, diminished lung capacity, wonky musculature around the vibrating air and sudden bursts of coughing made it hard to rehearse and perform. It’s quite upsetting to find your instrument unreliable. Something is physically making your voice not work and it is quite distressing, because when it is your body, nothing can really make the healing process go faster than it takes.

And Audience Echoes

Let’s be clear though, illness sucks even if you aren’t a performer. If you’re in the audience, sometimes the tension of trying not to make a sound makes you uncomfortable to the point where you’re no longer enjoying the music and instead just trying to be silent. I know many of my colleagues feel very strongly about audience noises. Some barely notice, but some take great issue with coughs and shuffles and the noises that crowds of hundreds of people make just by existing.

For me, any good performer can do their job, even when there is noise; the aural presence of the audience adds an ambience to the overall process of performing. Performing without an audience is just glorified rehearsal. Real audiences are made of real people and they make noises. They react to the music and they respond in kind. Think about how the energy in the room changes when everyone stands for the “Hallelujah Chorus” in Messiah – there is a visceral, physical and emotional change in the room. You don’t have to be a music aficionado to notice it, or more importantly, to feel changed by it. I like when there’s an audience, especially a big one, and I think most performing arts organizations would prefer you’re there, even if a bit noisy.

So, into this season of coughs, hacks, sneezes and other wintry ailments we go. Be healthy and get your flu shot! And be kind to the singers in your life, especially if we Purell ourselves religiously and take precautions to stay away from potential illness. We’re worried sick about losing our voices!

The Governor General’s Messiah

The newly installed Governor General, Julie Payette, once sang in the Tafelmusik Chamber Choir. She famously carried a recording of Tafelmusik’s Messiah with her into space. Her Excellency’s love of music will surely serve her well in her position as a grand patron of the arts in Canada.

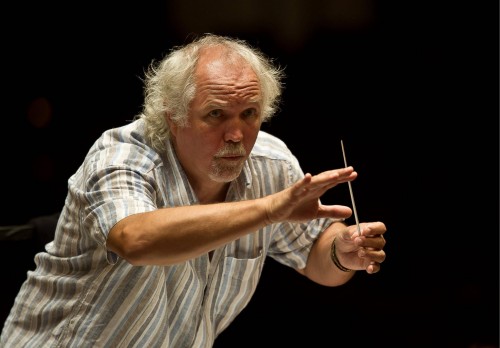

Tafelmusik’s annual Messiah continues to provide a period interpretation in the inimitable Koerner Hall, December 12 to 16. Ivars Taurins leads the ensembles. Presenting one of the smaller Messiah performances annually, Tafelmusik also presents the largest Messiah in town with its annual “Sing-Along Messiah” at Massey Hall, where 2,700 fans join the orchestra and choir in a grand tradition under the baton of the great maestro himself, Herr Handel (aka. Ivars Taurins), December 17 at 2pm.

Tafelmusik’s annual Messiah continues to provide a period interpretation in the inimitable Koerner Hall, December 12 to 16. Ivars Taurins leads the ensembles. Presenting one of the smaller Messiah performances annually, Tafelmusik also presents the largest Messiah in town with its annual “Sing-Along Messiah” at Massey Hall, where 2,700 fans join the orchestra and choir in a grand tradition under the baton of the great maestro himself, Herr Handel (aka. Ivars Taurins), December 17 at 2pm.

A Solid Choral Holiday at the TSO

The Toronto Symphony Orchestra (TSO) has an exceptionally choir-filled holiday season.

Home Alone in concert is being performed live with the Etobicoke School of the Arts Concert Choir, conducted by Constantine Kitsopoulos, November 30 to December 2. This beloved movie is very much a holiday favourite and one of John Williams’ most magical scores. “Somewhere in my Memory,” nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Song, has become a choral classic for the season.

Then, joining the TSO for the first time, Resonance Youth Choir from Mississauga makes its debut in Roy Thomson Hall on December 10 at 3pm. Only in its second season, Bob Anderson’s choir will join Tha Spot Holiday Dancers and TSYO Concerto Competition winner, cellist Dale Yoon Ho Jeong. Sing-along classics Jingle Bells, Joy to the World, Hark! The Herald Angels Sing and more are part of the program, as well as an excerpt from Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No.1. David Amado, music director of the Delaware Symphony and the Atlantic Music Festival, leads the groups. The main presentation will be live accompaniment of Howard Blake’s score to the holiday favourite film The Snowman.

No holiday season is complete without the TSO Pops Concert, featuring the Canadian Brass and the Etobicoke School of the Arts Holiday Chorus. Lucas Waldin conducts. The program December 12 and 13 looks magical, including bits from The Polar Express film, unique Canadian Brass arrangements like White Christmas, Go Tell it On the Mountain, The First Noël and carols arranged by TSO Pops conductor Stephen Reineke. (Waldin, who works with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra, was most recently in Toronto conducting the hugely popular and totally-sold-out TSO Carly Rae Jepsen performance.)

Last but not least, the TSO and Toronto Mendelssohn Choir presentation of Messiah promises to be as grand as ever. Matthew Halls, British early music specialist, takes the helm. This performance has an impeccable set of soloists: Karina Gauvin, soprano; Krisztina Szabó, mezzo-soprano; Frédéric Antoun, tenor; and Joshua Hopkins, baritone. December 18 to 23 in Roy Thomson Hall. (Barring an uncontrollable relapse into viral coughing, I’ll be there in my usual place in the Mendelssohn tenor section.)

The New Year

With most musical programming seasons running to the end of June, I’ve decided to highlight one performance from each of the next few months. They might make great gifts if you’re thinking ahead, and there are some you’ll surely want to secure seats to before they sell out.

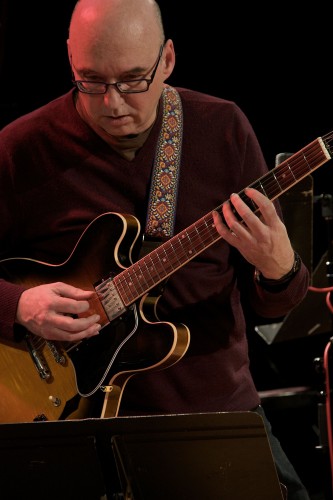

January: Annually, at the end of January, the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir hosts one of the most important training intensives for emerging conductors anywhere in North America. Under the supervision of Noel Edison, five symposium participants are exposed to a rigorous schedule of about 20 diverse songs from global choral repertoire and tested by the chamber-sized Elora Festival Singers and the symphonic, full Toronto Mendelssohn Choir. The week culminates with a free concert and a chance to see these conductors in action on January 27 at 3pm, Yorkminster Park Baptist Church, Toronto.

February: The Orpheus Choir presents “Nordic Light.” The Northern Lights, also known as the Aurora Borealis, have long captured the imagination and spirit of peoples in the far North. Indigenous peoples in Canada have an especially strong connection to their presence. Ēriks Ešenvalds, Latvian composer, has written Nordic Light Symphony. He will be in Toronto to introduce the work prior to the performance. This is the Canadian premiere of the work and a chance to experience Ešenvalds’ ethereal, atmospheric and deeply satisfying work, February 24 at 7:30pm, Metropolitan United Church, Toronto.

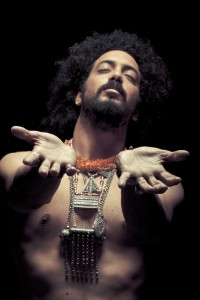

March: Soundstreams presents Tan Dun’s Water Passion. Choir 21, soloists and instruments are conducted by David Fallis. I’m deeply intrigued by the program. Billed as a reimagination of the Bach St. Matthew Passion. Dun’s East Asian musicality will weave a blending of the words of Christ through the theme of water, guided by Eastern musical traditions. From Mongolian overtone singing to Peking Opera to the sound of water, this promises to be an experience, March 9 at 8pm, Trinity-St. Pauls Centre, Toronto.

Follow Brian on Twitter @bfchang. Send info/media/tips to choralscene@thewholenote.com.