Although there were isolated experiments dating back to the 1940s, the watershed recording of saxophone solos was Anthony Braxton’s double LP For Alto in 1969. Comparably innovative sets by Evan Parker and Steve Lacy followed soon afterwards. Since then, many exploratory reedists have added their own challenging chapters to the solo saxophone literature.

Although there were isolated experiments dating back to the 1940s, the watershed recording of saxophone solos was Anthony Braxton’s double LP For Alto in 1969. Comparably innovative sets by Evan Parker and Steve Lacy followed soon afterwards. Since then, many exploratory reedists have added their own challenging chapters to the solo saxophone literature.

One of them is Braxton himself, whose most recently recorded alto foray is Solo – Victoriaville 2017 (Victo cd 130 victo.qc.ca), nine tracks from a concert at last year’s Festival International de Musique Actuelle de Victoriaville in Quebec. Nearly a half-century after For Alto, Braxton is still showcasing novel approaches. Interestingly enough, while all the tunes except for the standard Body and Soul have abstract titles, at this juncture hints of melodies and inferences to tunes as unanticipated as Everything Happens to Me, It’s Now or Never, Strike Up the Band and even The Anniversary Song insinuate themselves into the improvisations. This is no game of Name that Tune however, for Braxton’s talents are communicated through the technical alchemy obvious on each track. For instance, No 394c elongates the narrative line until it’s suddenly shaped into a balladic melody. The same sort of tunefulness informs the introductory No 392a; here, shaky cadenzas turn moderato when Braxton emphasizes the chalumeau register. At the same time no one would mistake Braxton for a member of Guy Lombardo’s sax section. Sophisticated funk works its way into the circular breathing and overblowing on No 392c, while its tremolo exposition showcases pauses and timbre extensions. More characteristically, No 394a consists of near-stifled reed screams, tongue slapping and pressurized action, culminating in terminal growling. Plus No 392b evolves with Flight of the Bumblebee-like buzzing swiftness, with multiple slurred and staccato notes tried on for size. As the balladic inferences slide by in nanoseconds, the improvisation’s finale is packed with innumerable pitches and tones. Yet, when Braxton tackles Body and Soul in tremolo double time, the distinctive theme is present along with a traditional final recapping of the head.

Three decades Braxton’s junior, Chicago’s Dave Rempis follows an analogous but distinct route on Lattice (Aerophonic 015 aerophonicrecords.com) by bookending his improvisations with two jazz standards. Although Rempis plays alto, tenor and baritone saxophone, his strategy is similar on each horn – using its distinctive properties to better describe the improvisations. Billy Strayhorn’s A Flower is a Lovesome Thing and Eric Dolphy’s Serene are treated no differently than the abstract improvisations. Playing baritone on the former, he digs deep, shaking textures from the instrument’s body tube that accelerate from snorts to screams before creating variations on a mellow version of the theme. Dolphy’s avant-garde credentials are emphasized with stratospheric whistles, duck quacks and chicken cackles in the middle of Serene following a near inchoate theme elaboration by the alto saxophone. However the piece climaxes with rhapsodic mellowness and the head recapped. The most impressive instance of Rempis’ solo musicianship is on If You Get Lost in Santa Paula, where he inveigles a collection of tongue slaps and pops into captivating textures that are almost danceable and certainly rhythmic, then maintains this mouth percussion until the end. A track like Horse Court demonstrates how he can output enough bites and beeps for two saxophonists in counterpoint while using spatial dimensions to bounce back the sound; meanwhile Loose Snus proves that split tones and spetrofluctuation can be vibrated into satisfying storytelling.

Three decades Braxton’s junior, Chicago’s Dave Rempis follows an analogous but distinct route on Lattice (Aerophonic 015 aerophonicrecords.com) by bookending his improvisations with two jazz standards. Although Rempis plays alto, tenor and baritone saxophone, his strategy is similar on each horn – using its distinctive properties to better describe the improvisations. Billy Strayhorn’s A Flower is a Lovesome Thing and Eric Dolphy’s Serene are treated no differently than the abstract improvisations. Playing baritone on the former, he digs deep, shaking textures from the instrument’s body tube that accelerate from snorts to screams before creating variations on a mellow version of the theme. Dolphy’s avant-garde credentials are emphasized with stratospheric whistles, duck quacks and chicken cackles in the middle of Serene following a near inchoate theme elaboration by the alto saxophone. However the piece climaxes with rhapsodic mellowness and the head recapped. The most impressive instance of Rempis’ solo musicianship is on If You Get Lost in Santa Paula, where he inveigles a collection of tongue slaps and pops into captivating textures that are almost danceable and certainly rhythmic, then maintains this mouth percussion until the end. A track like Horse Court demonstrates how he can output enough bites and beeps for two saxophonists in counterpoint while using spatial dimensions to bounce back the sound; meanwhile Loose Snus proves that split tones and spetrofluctuation can be vibrated into satisfying storytelling.

Swedish alto saxophonist Martin Küchen is also involved with spatial properties since Lieber Heiland, laß uns sterben (SOFA Music 60 sofamusic.no) was recorded in the crypt of the cathedral in Lund, Sweden and utilizes field recording, an iPod, speakers and electronics plus overdubbed saxophone lines. An idea of how this works is Ruf Zu Mer Bezprizorni…, where the distant sounds of piano students rehearsing Baroque classics cause Küchen to retaliate with mocking squeaks and puffs, plus percussive slaps that emphasize the saxophone’s metal body. Music To Silence Music in contrast makes the ancient crypt walls another instrument, as they vibrate and echo back the initial saxophone lowing and air-piercing extensions, the equivalent of overdubbed reed parts. Real overdubbing to a multiple of six is used on Amen Choir, but when coupled with low-pitched electronic drones and the outdoor noises leaking into the space, the results not only almost replicate scrubs and sawing on double bass strings, but also suggest a near visual picture of reed breaths floating across the sound field. Far-off pealing church bells make the perfect coda. Küchen’s solo design has non-Western precedents as well, as on Purcell in the Eternal Deir Yassin. Traces of the 17th-century composer’s music drift though an open window via a bel canto soprano’s vocalizing; more prominent are Indian influences, with an electronic tambura providing an appropriately sub-continental drone, while voluminous reed tones side-slip into various keys and pitches.

Swedish alto saxophonist Martin Küchen is also involved with spatial properties since Lieber Heiland, laß uns sterben (SOFA Music 60 sofamusic.no) was recorded in the crypt of the cathedral in Lund, Sweden and utilizes field recording, an iPod, speakers and electronics plus overdubbed saxophone lines. An idea of how this works is Ruf Zu Mer Bezprizorni…, where the distant sounds of piano students rehearsing Baroque classics cause Küchen to retaliate with mocking squeaks and puffs, plus percussive slaps that emphasize the saxophone’s metal body. Music To Silence Music in contrast makes the ancient crypt walls another instrument, as they vibrate and echo back the initial saxophone lowing and air-piercing extensions, the equivalent of overdubbed reed parts. Real overdubbing to a multiple of six is used on Amen Choir, but when coupled with low-pitched electronic drones and the outdoor noises leaking into the space, the results not only almost replicate scrubs and sawing on double bass strings, but also suggest a near visual picture of reed breaths floating across the sound field. Far-off pealing church bells make the perfect coda. Küchen’s solo design has non-Western precedents as well, as on Purcell in the Eternal Deir Yassin. Traces of the 17th-century composer’s music drift though an open window via a bel canto soprano’s vocalizing; more prominent are Indian influences, with an electronic tambura providing an appropriately sub-continental drone, while voluminous reed tones side-slip into various keys and pitches.

This sort of solo contemplation is actually connected to an instrument’s technical versatility, rather than its nationalism. It’s the same way that Lithuanian soprano and tenor saxophonist Liudas Mockŭnas’ improvisations on Hydro (NoBusiness NBLP 110 nobusinessrecords.com) lack any overt Baltic musical inferences. But considering the titles of the seven-part Hydration Suite, three-part Rehydration Suite, and the final extended Dehydration, his relationship with the sea is highlighted. Conspicuously by utilizing “water-prepared” (sic) saxophones, the Hydration Suite includes liquid-related sounds, while denser echoes from vibrations of potential coastal and submerged objects share space with the saxophonist’s moist hiccups and puffs, plus seabird-like wails that expand or recede in degrees of pitch and volume. Oddly enough, Hydration Suite part 5, the most abstract outpouring, with dot-dash, kazoo-like treble textures, seemingly only using the sax mouthpiece, precedes the suite’s final sequences, which are delicate and almost vibrato-less. Melodic and expressive, the gentle curlicues could come from a so-called “legit” player. Wolf-like snarls and staccato peeping characterize the Rehydration Suite, but the track also emphasizes Mockŭnas’ reed fluidity, encompassing circular breathing, emphatic screams and gut-propelled emotional sweeps. A compendium of the preceding techniques, the multi-tempo Dehydration showcases the saxophone’s farthest reaches, including pressurized vibratos, whinnying cries falling up instead of down, and gusts that appear to be blowing any remaining water from his instrument, with pure air and key jiggling.

This sort of solo contemplation is actually connected to an instrument’s technical versatility, rather than its nationalism. It’s the same way that Lithuanian soprano and tenor saxophonist Liudas Mockŭnas’ improvisations on Hydro (NoBusiness NBLP 110 nobusinessrecords.com) lack any overt Baltic musical inferences. But considering the titles of the seven-part Hydration Suite, three-part Rehydration Suite, and the final extended Dehydration, his relationship with the sea is highlighted. Conspicuously by utilizing “water-prepared” (sic) saxophones, the Hydration Suite includes liquid-related sounds, while denser echoes from vibrations of potential coastal and submerged objects share space with the saxophonist’s moist hiccups and puffs, plus seabird-like wails that expand or recede in degrees of pitch and volume. Oddly enough, Hydration Suite part 5, the most abstract outpouring, with dot-dash, kazoo-like treble textures, seemingly only using the sax mouthpiece, precedes the suite’s final sequences, which are delicate and almost vibrato-less. Melodic and expressive, the gentle curlicues could come from a so-called “legit” player. Wolf-like snarls and staccato peeping characterize the Rehydration Suite, but the track also emphasizes Mockŭnas’ reed fluidity, encompassing circular breathing, emphatic screams and gut-propelled emotional sweeps. A compendium of the preceding techniques, the multi-tempo Dehydration showcases the saxophone’s farthest reaches, including pressurized vibratos, whinnying cries falling up instead of down, and gusts that appear to be blowing any remaining water from his instrument, with pure air and key jiggling.

An individual adaptation of the equipment used by the likes of Küchen and Mockŭnas is offered by New York’s Jonah Parzen-Johnson, who plays baritone saxophone tones alongside an analog synthesizer’s textures. I Try To Remember Where I Come From (Clean Feed CF 430 CD cleanfeed-records.com) contains seven instances where his overblowing and split tones play catch-as-catch-can with the electronics. Avoiding loops, overdubbing or sampling, gutty textures either arise from mouth-propelled blowing or live processing. Since his preference is for simple, song-based material, the result is unlike any other CD here. Parzen-Johnson sparingly utilizes multiphonic screams or thickened vibrating quavering tones. On tracks such as Too Many Dreams, he comes across as if he were a folk or country balladeer, with the synthesizer taking the place of a backing combo. The machine can also deflect his sax’s tones back at him, doubling his exposition, but here and elsewhere he manages to overcome the dangers of reed overpowering with skill. While the title tune sets up distinctive contrasts between unaccented puffs and burbles from the baritone and the synthesizer’s pipe-organ-like cascades, What Do I Do with Sorry is the most notable track, since the split-second transformations come from man as well as machine. With his output shaped as if he were playing a bagpipe chanter and the synthesizer responding as if it were the bagpipe’s reservoir bag, Parzen-Johnson’s improvising takes on buzzing, triple-tongued aspects while the synthesizer’s echoing pulsations suggest both Celtic airs and the beats from a club DJ.

An individual adaptation of the equipment used by the likes of Küchen and Mockŭnas is offered by New York’s Jonah Parzen-Johnson, who plays baritone saxophone tones alongside an analog synthesizer’s textures. I Try To Remember Where I Come From (Clean Feed CF 430 CD cleanfeed-records.com) contains seven instances where his overblowing and split tones play catch-as-catch-can with the electronics. Avoiding loops, overdubbing or sampling, gutty textures either arise from mouth-propelled blowing or live processing. Since his preference is for simple, song-based material, the result is unlike any other CD here. Parzen-Johnson sparingly utilizes multiphonic screams or thickened vibrating quavering tones. On tracks such as Too Many Dreams, he comes across as if he were a folk or country balladeer, with the synthesizer taking the place of a backing combo. The machine can also deflect his sax’s tones back at him, doubling his exposition, but here and elsewhere he manages to overcome the dangers of reed overpowering with skill. While the title tune sets up distinctive contrasts between unaccented puffs and burbles from the baritone and the synthesizer’s pipe-organ-like cascades, What Do I Do with Sorry is the most notable track, since the split-second transformations come from man as well as machine. With his output shaped as if he were playing a bagpipe chanter and the synthesizer responding as if it were the bagpipe’s reservoir bag, Parzen-Johnson’s improvising takes on buzzing, triple-tongued aspects while the synthesizer’s echoing pulsations suggest both Celtic airs and the beats from a club DJ.

There may be as many ways to play solo saxophone as there are saxophonists, and these are a few instances of how it is done.

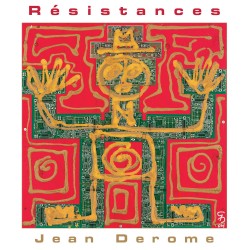

Résistances

Résistances