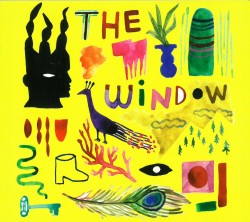

The Window - Cécile McLorin Salvant

The Window

The Window

Cécile McLorin Salvant

Justin Time JTR 8614-2 (justin-time.com)

Cécile McLorin Salvant frames her vision of love through The Window, but this ubiquitous architectural element has been thrown so wide open that it is now a glorious metaphor, its theme spread out as vast as a lifetime of beauty against a blushing sky. And McLorin Salvant’s reputation as the premier jazz vocalist in any era has been fortified as she picks up effortlessly from where the legends such as Billie Holiday left off.

McLorin Salvant is magical as she strips lyrics and narrative bare in this duo format with the incomparable pianist Sullivan Fortner, achieving – if such as thing is possible – the closest equivalent of Jazz Lieder. Songs speak to McLorin Salvant as a lover’s whispers might. When she blushes so does her lyric, when she is in pain, her heartache puts a twist in the listener’s gut and her joyous enunciations create shivers down the spine. The Peacocks featuring saxophonist Melissa Aldana is a haunting example.

On Tracy Mann’s lyrics to Brazilian songsters Dori Caymmi and Gilson Peranzzetta’s Obsession, McLorin Salvant literally detonates the lines, “You’re like the wind that blows in front of a storm/The electricity explodes in the night.” Her instrument is lustrous, precise and feather-light; her musicianship fierce as she digs into the expression of each word; brings ceaseless variety to soft dynamics and gives every phrase grace. Fortner is here, an equal partner in the creation of the song’s character; his pianism rising to a rarefied realm.