As the availability of music on different media continues to proliferate, the focus of the durable box set has become equally diverse. No longer does a multi-disc collection have to be definitive or far-ranging. As a matter of fact some of the best, like the ones discussed here, concentrate on certain sequences in an artist’s career.

Case in point is Discography (Jazz Werksttatt JW 150 jazzwerkstatt.eu), a four-CD collection of sessions from the 1980s and 1990s by German bassist Peter Kowald (1944-2002). Someone who began his career in the 1960s ground zero for European Free Jazz, over the years Kowald interacted with those playing mainstream and contemporary jazz as well as making forays into cross-cultural improv with non-Western players. His recorded career, with disc cover pictures and personnel, is outlined in the 210-page booklet included with the set. Still the focus of Discography is Kowald’s Free Jazz achievements. Right off the bat, Solo Improvisation Music on CD1 is a 35-minute tour-de-force from 1981 that captures his unvarnished inventiveness. Showcasing equal facility with fingers or bow, he moves seamlessly from strident smacks and slashing strums to a collection of spiccato rubs and rasps producing aviary-like shrills as well as mellow continuum. Discography also highlights the talents of Greek clarinetist/saxophonist Floros Floridis, a frequent Kowald playing partner. Compare how the two reacted without prevarication in different settings. A 1989 Athens session, for instance, emphasizes the music’s bop and blues roots, due to the inimitable time-keeping of American drum master Andrew Cyrille. At the same time as Kowald’s doubled strokes steady the beat alongside Cyrille, jocular intensity on tunes such as Nice Ending Folks! and Points Slashes Etc. is expressed by Floridis’ fluid clarinet flutters and vocalized blats from German trombonist Conny Bauer. Six tracks from the next year are more expansive since Kowald’s and Floridis’ partners are American French hornist Vincent Chancy and South African drummer Louis Moholo. Kowald’s careful note placement gives the proceedings a lighter feel as the four prove themselves on both spirited and sorrowful tunes. The Spell is one of the latter as Chancy’s facility emphasizes not only melancholic cries, but animates the tune through steady pacing. With verbal interjections from Moholo Mongezi is another standout since tough vibrations from the horn and Floridis’ saxophone reed bites work up to freneticism as pulsating power from the bass and percussion keep the narrative snappy. Even better is CD4 from 1997 where Floridis on alto and soprano saxophones, clarinet and bass clarinet, Kowald and German percussionist Günter Baby Sommer – featured with the bassist on a long improvisation on CD1 – turn out 26 brief “Aphorisms.” Ranging from less than one minute to almost two and a half, the concise motifs express everything that others would need greater length to do. A track like Aphorismus III for instance features Kowald strumming what sounds like telephone-wire thick strings, Sommer pinging gamelan-like bells and Floridis’ smooth soprano sax surmounting both. Aphorismus XI is pure jazz with mountaineering thumps from the drummer, spiccato bass strokes and reed bites; while Aphorismus VI parallels clarinet tongue-slaps with bagpipe-like tremolos from the bass. Floridis’ alto saxophone tone can be as sharp as any bopper’s as it is on Aphorismus XVII; while percussion clip-clops are sophisticatedly smoothed into a connective exposition on Aphorismus XIX. The program ends with Sommer affectionately mocking Kowald’s chamber music-like sweeps and Floridis’ delicate clarinet lines with obtrusive Jew’s harp twangs.

Case in point is Discography (Jazz Werksttatt JW 150 jazzwerkstatt.eu), a four-CD collection of sessions from the 1980s and 1990s by German bassist Peter Kowald (1944-2002). Someone who began his career in the 1960s ground zero for European Free Jazz, over the years Kowald interacted with those playing mainstream and contemporary jazz as well as making forays into cross-cultural improv with non-Western players. His recorded career, with disc cover pictures and personnel, is outlined in the 210-page booklet included with the set. Still the focus of Discography is Kowald’s Free Jazz achievements. Right off the bat, Solo Improvisation Music on CD1 is a 35-minute tour-de-force from 1981 that captures his unvarnished inventiveness. Showcasing equal facility with fingers or bow, he moves seamlessly from strident smacks and slashing strums to a collection of spiccato rubs and rasps producing aviary-like shrills as well as mellow continuum. Discography also highlights the talents of Greek clarinetist/saxophonist Floros Floridis, a frequent Kowald playing partner. Compare how the two reacted without prevarication in different settings. A 1989 Athens session, for instance, emphasizes the music’s bop and blues roots, due to the inimitable time-keeping of American drum master Andrew Cyrille. At the same time as Kowald’s doubled strokes steady the beat alongside Cyrille, jocular intensity on tunes such as Nice Ending Folks! and Points Slashes Etc. is expressed by Floridis’ fluid clarinet flutters and vocalized blats from German trombonist Conny Bauer. Six tracks from the next year are more expansive since Kowald’s and Floridis’ partners are American French hornist Vincent Chancy and South African drummer Louis Moholo. Kowald’s careful note placement gives the proceedings a lighter feel as the four prove themselves on both spirited and sorrowful tunes. The Spell is one of the latter as Chancy’s facility emphasizes not only melancholic cries, but animates the tune through steady pacing. With verbal interjections from Moholo Mongezi is another standout since tough vibrations from the horn and Floridis’ saxophone reed bites work up to freneticism as pulsating power from the bass and percussion keep the narrative snappy. Even better is CD4 from 1997 where Floridis on alto and soprano saxophones, clarinet and bass clarinet, Kowald and German percussionist Günter Baby Sommer – featured with the bassist on a long improvisation on CD1 – turn out 26 brief “Aphorisms.” Ranging from less than one minute to almost two and a half, the concise motifs express everything that others would need greater length to do. A track like Aphorismus III for instance features Kowald strumming what sounds like telephone-wire thick strings, Sommer pinging gamelan-like bells and Floridis’ smooth soprano sax surmounting both. Aphorismus XI is pure jazz with mountaineering thumps from the drummer, spiccato bass strokes and reed bites; while Aphorismus VI parallels clarinet tongue-slaps with bagpipe-like tremolos from the bass. Floridis’ alto saxophone tone can be as sharp as any bopper’s as it is on Aphorismus XVII; while percussion clip-clops are sophisticatedly smoothed into a connective exposition on Aphorismus XIX. The program ends with Sommer affectionately mocking Kowald’s chamber music-like sweeps and Floridis’ delicate clarinet lines with obtrusive Jew’s harp twangs.

More chronologically limited, but even more spectacular in probing the boundaries of a jazz formation is Die Kunst des Trio 1-5 (BMC Records BMC CD 196 bmcrecords.hu). During the course of five CDs and a bonus DVD, Cologne-based pianist Hans Lüdemann works through programs involving five unique bass and drum teams. Able to express high-energy complexity and florid impressionism with the same finesse, Lüdemann’s trios showcase original compositions plus Hanns Eisler ballads from the latter’s Hollywood period. All 36 tracks, recorded at the same location, are performed acoustically aside from the sets with electric bass and percussion. Sophisticated in mining perceptive emotions with both acoustic and electronic keyboards, Rhythm Magic is Lüdemann’s weakest program. That’s because bass guitar sluices, percussion patter and staccato key flourishes excite only the tapping foot rather than the thinking brain. Conversely, Chiffre, featuring bassist/cellist Henning Sieverts plus percussionist Eric Shaefer, confirms the adage that the best is often left for last. Able to make the virtual piano as sensitive to cerebral explorations as the real McCoy, Lüdemann creatively exposes the tunes’ reflective innards on CD5. Slow paced Doux for example unites keyboard cascades with piercing multi-string actions that could come from a viola da gamba. Meanwhile the climatic minutes of Verioren that result from the pianist’s near-boogie-woogie patterning are cannily set up with bell peals and impressionistic multi-string vibrations at the top. This is the most impressive trio music, but there’s also much to be said for the pianist’s interaction with bassist Robert Landfermann and drummer Jonas Burgwinkel plus bassist Sébastien Boisseau and drummer Dejan Terzic. The first mixes kinetic piano lines, drum pumps and quirky bass voicing to extend the classic piano trio to include European tropes such as suggestions of baroque stylings plus electronic add-ons. Even better is the Boisseau-Terzic meeting. Dramatic and cerebral, sturdy bass lines and clattering drums aid the pianist’s careful pacing of particular themes. Paradoxically this strategy is impressive on Über den Selbstmord/Das ist gefährlich where Lüdemann sutures harmonic swing onto the Eisler song which starts the track. This type of transformative alchemy is extended throughout the nine tunes that make up Eisler’s Exile. Seconded by bassist Dieter Manderscheid and percussionist Christian Thomé, the pianist never neglects the romantic yearnings which inhabit the German composer’s original intent. At the same time he invests each track with sinewy swing.

More chronologically limited, but even more spectacular in probing the boundaries of a jazz formation is Die Kunst des Trio 1-5 (BMC Records BMC CD 196 bmcrecords.hu). During the course of five CDs and a bonus DVD, Cologne-based pianist Hans Lüdemann works through programs involving five unique bass and drum teams. Able to express high-energy complexity and florid impressionism with the same finesse, Lüdemann’s trios showcase original compositions plus Hanns Eisler ballads from the latter’s Hollywood period. All 36 tracks, recorded at the same location, are performed acoustically aside from the sets with electric bass and percussion. Sophisticated in mining perceptive emotions with both acoustic and electronic keyboards, Rhythm Magic is Lüdemann’s weakest program. That’s because bass guitar sluices, percussion patter and staccato key flourishes excite only the tapping foot rather than the thinking brain. Conversely, Chiffre, featuring bassist/cellist Henning Sieverts plus percussionist Eric Shaefer, confirms the adage that the best is often left for last. Able to make the virtual piano as sensitive to cerebral explorations as the real McCoy, Lüdemann creatively exposes the tunes’ reflective innards on CD5. Slow paced Doux for example unites keyboard cascades with piercing multi-string actions that could come from a viola da gamba. Meanwhile the climatic minutes of Verioren that result from the pianist’s near-boogie-woogie patterning are cannily set up with bell peals and impressionistic multi-string vibrations at the top. This is the most impressive trio music, but there’s also much to be said for the pianist’s interaction with bassist Robert Landfermann and drummer Jonas Burgwinkel plus bassist Sébastien Boisseau and drummer Dejan Terzic. The first mixes kinetic piano lines, drum pumps and quirky bass voicing to extend the classic piano trio to include European tropes such as suggestions of baroque stylings plus electronic add-ons. Even better is the Boisseau-Terzic meeting. Dramatic and cerebral, sturdy bass lines and clattering drums aid the pianist’s careful pacing of particular themes. Paradoxically this strategy is impressive on Über den Selbstmord/Das ist gefährlich where Lüdemann sutures harmonic swing onto the Eisler song which starts the track. This type of transformative alchemy is extended throughout the nine tunes that make up Eisler’s Exile. Seconded by bassist Dieter Manderscheid and percussionist Christian Thomé, the pianist never neglects the romantic yearnings which inhabit the German composer’s original intent. At the same time he invests each track with sinewy swing.

In a technological age a boxed set takes on many meanings. For instancecornetist Taylor Ho Bynum 7-tette’s Navigation [Possibility Abstracts XII & XIII] (Firehouse 12 Records FH-12-04-01-019 firehouse12.com) is available as two CDs of a studio session and on a double LP as a live date. Different variations on Bynum’s Navigation composition, each package includes complimentary download codes to access digital copies of the other format. Using graphic and conventional methods to guide the improvisation, Bynum calls on tropes encompassing tremolo theme repetition and stop-time climaxes, plus intersection and interpolation of riffs and sudden narrative punctuation from a band that includes trombonist Bill Lowe, alto saxophonist Jim Hobbs, guitarist Mary Halvorson and bassist Ken Filiano with Tomas Fujiwara and Chad Taylor on drums and vibraphones. Comparing versions of March from the CD set demonstrates the group’s versatility. While it’s undisputedly the same tune, solo emphasis gives it novel allure in each instance. Introducing the second CD, March features sharp saxophone lines in violin register that quickly give way to scene-setting trombone slurs. From that point until the finale, the sequence takes on a New Orleans-like cast as two-beat drumming backs clanking guitar runs and taut cornet expositions. When March ends the first CD though, the quasi-Dixieland emphasis is downplayed for sophisticated solos. Hobbs’ wide glissandi limn the theme atop cohesive brass vamps, until a Halvorson-Bynum duo that simultaneously manages to suggest the power of early Louis Armstrong’s small groups while slyly interpolating bop modernism.

In a technological age a boxed set takes on many meanings. For instancecornetist Taylor Ho Bynum 7-tette’s Navigation [Possibility Abstracts XII & XIII] (Firehouse 12 Records FH-12-04-01-019 firehouse12.com) is available as two CDs of a studio session and on a double LP as a live date. Different variations on Bynum’s Navigation composition, each package includes complimentary download codes to access digital copies of the other format. Using graphic and conventional methods to guide the improvisation, Bynum calls on tropes encompassing tremolo theme repetition and stop-time climaxes, plus intersection and interpolation of riffs and sudden narrative punctuation from a band that includes trombonist Bill Lowe, alto saxophonist Jim Hobbs, guitarist Mary Halvorson and bassist Ken Filiano with Tomas Fujiwara and Chad Taylor on drums and vibraphones. Comparing versions of March from the CD set demonstrates the group’s versatility. While it’s undisputedly the same tune, solo emphasis gives it novel allure in each instance. Introducing the second CD, March features sharp saxophone lines in violin register that quickly give way to scene-setting trombone slurs. From that point until the finale, the sequence takes on a New Orleans-like cast as two-beat drumming backs clanking guitar runs and taut cornet expositions. When March ends the first CD though, the quasi-Dixieland emphasis is downplayed for sophisticated solos. Hobbs’ wide glissandi limn the theme atop cohesive brass vamps, until a Halvorson-Bynum duo that simultaneously manages to suggest the power of early Louis Armstrong’s small groups while slyly interpolating bop modernism.

Taking this download concept one step further, the 15-piece Belgian jazz-rock-experimental big band the Flat Earth Society (FES) has come up with FESXLS (Igloo IGL 257 fes.be/indexEN.html). The three-CD package includes two discs celebrating the Flemish orchestra’s – and guests’ – recent projects; a single CD, featuring tracks from the more rock-oriented X-Legged Sally band that evolved into Flat Earth Society; plus 12 (!) download codes allowing the listener to get digital copies of additional albums. Even without the digital discs, the physical package is fascinating. Over the course of 19 tracks on X-Legged Sally 1988-1997, the listener can track how the shifting personnel of the group, always led by multi-instrumentalist/composer Peter Vermeersch, gradually shifted from a defiant vocal and instrumental combo, influenced by Frank Zappa and other avant-rockers, into a high-energy instrumental group whose staccato expositions melded jazz-influenced soloing, rock energy and instrumental chops. Mutating into the FES, the contemporary CDs, Boot & Berg and Call Sheets, Riders & Chicken Mushroom are even more striking. Although its Flemish libretto may be difficult for those who don’t know the language, the sheer musicianship of the FES matched with soprano Rolande Van der Paal shines through the language barrier on Boot & Berg. A multimedia retelling of the Titanic tragedy on the 100th anniversary of that disaster, Vermeersch’s music introduces motifs from nautical melodies, hard rock, Count Basie-like-swing and so-called classical counterpoint which scene-set, then integrate Van der Paal’s lyric soprano within the exposition. Particularly expressive during an intermezzo where cracked instrumental tones shade the vocalist’s sophisticated cabaret-style declarations, booming and whistling textures from the band emphasize the emotions involved as much as Van der Paal’s bel canto delivery. A different matter Call Sheets, Riders & Chicken Mushroom is 15 FES live tracks, with featured spots for guest improvisers such as American pianist Uri Caine, Dutch cellist Ernst Reijseger and Belgium’s most famous jazzer, harmonica player Toots Thielemans. While the quiet-jazz setting of Hilton’s Heaven, Thielemans’ first outing, is all smooth harmonica reeds cushioned by muted horns and vibes, Zonk puts him in a novel setting. Like what a Basie band standard would sound like if played by a heavy metal band, the tune finds the harmonica master expanding on cues from the jagged vamps until the piece is taken out with a graceful trumpet solo. The Caine track is even weirder since during Fes 9 the urbane keyboardist takes a solo that mixes bop with Little Richard-like excess and ends with some pseudo-ragtime, as plunger trombone smears and swelling organ riffs explode around him. At the same time this CD confirms that FES can easily be appreciated on its own. In Between Rivers for instance is a standout ballad that manages to shoehorn accordion tremors into an Ellington Jungle Band-style arrangement as reed flutters and warm brass slurs keep the narrative comfortable.

Taking this download concept one step further, the 15-piece Belgian jazz-rock-experimental big band the Flat Earth Society (FES) has come up with FESXLS (Igloo IGL 257 fes.be/indexEN.html). The three-CD package includes two discs celebrating the Flemish orchestra’s – and guests’ – recent projects; a single CD, featuring tracks from the more rock-oriented X-Legged Sally band that evolved into Flat Earth Society; plus 12 (!) download codes allowing the listener to get digital copies of additional albums. Even without the digital discs, the physical package is fascinating. Over the course of 19 tracks on X-Legged Sally 1988-1997, the listener can track how the shifting personnel of the group, always led by multi-instrumentalist/composer Peter Vermeersch, gradually shifted from a defiant vocal and instrumental combo, influenced by Frank Zappa and other avant-rockers, into a high-energy instrumental group whose staccato expositions melded jazz-influenced soloing, rock energy and instrumental chops. Mutating into the FES, the contemporary CDs, Boot & Berg and Call Sheets, Riders & Chicken Mushroom are even more striking. Although its Flemish libretto may be difficult for those who don’t know the language, the sheer musicianship of the FES matched with soprano Rolande Van der Paal shines through the language barrier on Boot & Berg. A multimedia retelling of the Titanic tragedy on the 100th anniversary of that disaster, Vermeersch’s music introduces motifs from nautical melodies, hard rock, Count Basie-like-swing and so-called classical counterpoint which scene-set, then integrate Van der Paal’s lyric soprano within the exposition. Particularly expressive during an intermezzo where cracked instrumental tones shade the vocalist’s sophisticated cabaret-style declarations, booming and whistling textures from the band emphasize the emotions involved as much as Van der Paal’s bel canto delivery. A different matter Call Sheets, Riders & Chicken Mushroom is 15 FES live tracks, with featured spots for guest improvisers such as American pianist Uri Caine, Dutch cellist Ernst Reijseger and Belgium’s most famous jazzer, harmonica player Toots Thielemans. While the quiet-jazz setting of Hilton’s Heaven, Thielemans’ first outing, is all smooth harmonica reeds cushioned by muted horns and vibes, Zonk puts him in a novel setting. Like what a Basie band standard would sound like if played by a heavy metal band, the tune finds the harmonica master expanding on cues from the jagged vamps until the piece is taken out with a graceful trumpet solo. The Caine track is even weirder since during Fes 9 the urbane keyboardist takes a solo that mixes bop with Little Richard-like excess and ends with some pseudo-ragtime, as plunger trombone smears and swelling organ riffs explode around him. At the same time this CD confirms that FES can easily be appreciated on its own. In Between Rivers for instance is a standout ballad that manages to shoehorn accordion tremors into an Ellington Jungle Band-style arrangement as reed flutters and warm brass slurs keep the narrative comfortable.

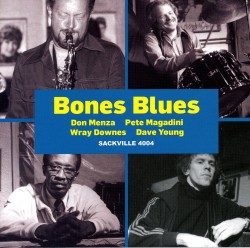

Bones Blues

Bones Blues

Guitar in the Space Age

Guitar in the Space Age