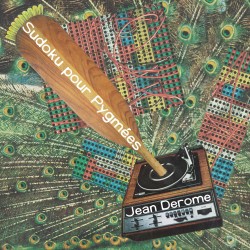

Sudoku pour Pygmées - Jean Derome

Sudoku pour Pygmées

Sudoku pour Pygmées

Jean Derome

Ambiances Magnetiques AM 242 CD (actuellecd.com)

Composer, saxophonist and flutist Jean Derome has been a central voice in Quebec’s musique actuelle movement for decades, along the way creating works that fuse improvisation with larger structural forms. Here he leads his quartet Les Dangereux Zhoms and nine other musicians in a cross-country retrospective of works commissioned by Canada’s landmark mixed-method contemporary ensembles.

The title track, originally performed by Halifax’s Upstream in 2010, uses the idea of the Sudoku puzzle to create polyphonic canons of pentatonic scales in a way that suggests Pygmy vocal music. It’s a scintillating work, leavening its complexity with sonic transparency and some brilliant reed soloists, most notably Derome on baritone saxophone and André Leroux on tenor. 7 danses (pour <<15>>), originally performed by Toronto’s Hemispheres in 1989, demonstrates Derome’s longstanding interest in creating hybrid works, juxtaposing popular and serious genres that mingle Bernard Falaise’s rock-inspired electric guitar with abstract harmonies.

The concluding 5 pensées (pour le caoutchouc dur), composed for Vancouver’s Hard Rubber Orchestra in 2001, encompasses a range of moods and inspirations and highlights some of the group’s strongest voices. The playful second pensée, suggests Thelonious Monk’s work, with Lori Freedman’s bass clarinet approaching comic speech, while the third invokes Duke Ellington’s sacred music, with a pensive, reflective lead provided by trombonist Scott Thomson. The concluding Pensée matches a rapid hoedown with anarchic collective improvisation, literally an ultimate stylistic collision, and the ideal conclusion for this boundary-blurring set of works.