Anthony Braxton – composer, theorist, master of reeds, philosopher of play – has been recording for over half a century now and has often done so exhaustively. It began in 1969, when the recorded history of improvised solo wind performances consisted of a few brief pieces by Coleman Hawkins, Sonny Rollins, Eric Dolphy and Jimmy Giuffre. The young Braxton declared his arrival with a two-LP solo set called For Alto, outlining a musical language that he’s been exploring and expanding ever since, with larger and larger projects and titles ever more evocative or mysterious, like the Ghost Trance Music and Diamond Curtain Wall. In 2019, in his 75th year, he presented a six-hour performance of Sonic Genome at Berlin’s Gropius Bau, with 60 musicians spread throughout the museum drawing randomly from Braxton’s vast compositional output. Graham Lock suggested his significance in the subtitle of his book Blutopia: Visions of the Future and Revisions of the Past in the Work of Sun Ra, Duke Ellington, and Anthony Braxton. Possible alternatives? You might as readily match Braxton with Olivier Messiaen, Karlheinz Stockhausen or Harry Partch as a composer who has constructed his own universe.

Anthony Braxton – composer, theorist, master of reeds, philosopher of play – has been recording for over half a century now and has often done so exhaustively. It began in 1969, when the recorded history of improvised solo wind performances consisted of a few brief pieces by Coleman Hawkins, Sonny Rollins, Eric Dolphy and Jimmy Giuffre. The young Braxton declared his arrival with a two-LP solo set called For Alto, outlining a musical language that he’s been exploring and expanding ever since, with larger and larger projects and titles ever more evocative or mysterious, like the Ghost Trance Music and Diamond Curtain Wall. In 2019, in his 75th year, he presented a six-hour performance of Sonic Genome at Berlin’s Gropius Bau, with 60 musicians spread throughout the museum drawing randomly from Braxton’s vast compositional output. Graham Lock suggested his significance in the subtitle of his book Blutopia: Visions of the Future and Revisions of the Past in the Work of Sun Ra, Duke Ellington, and Anthony Braxton. Possible alternatives? You might as readily match Braxton with Olivier Messiaen, Karlheinz Stockhausen or Harry Partch as a composer who has constructed his own universe.

Braxton’s latest compositional series is called ZIM – Anthony Braxton: 12 COMP (ZIM) 2017 (Firehouse 12 tricentricfoundation.org; firehouse12records.com). He has just released its first substantial documentation on a single audio Blu-ray disc: 12 pieces, ranging from 40 to 73 minutes each, over ten hours altogether, recorded over a 14-month period by groups ranging from sextet to nonet in the U.S., Montreal and London. As usual though, the real wonder of Braxton’s work is in the listening, not the clock-watching, despite the hourglass he will place on a stage at the start of a piece, signal of a time apart: ancient, infinite, even granular.

Braxton’s latest compositional series is called ZIM – Anthony Braxton: 12 COMP (ZIM) 2017 (Firehouse 12 tricentricfoundation.org; firehouse12records.com). He has just released its first substantial documentation on a single audio Blu-ray disc: 12 pieces, ranging from 40 to 73 minutes each, over ten hours altogether, recorded over a 14-month period by groups ranging from sextet to nonet in the U.S., Montreal and London. As usual though, the real wonder of Braxton’s work is in the listening, not the clock-watching, despite the hourglass he will place on a stage at the start of a piece, signal of a time apart: ancient, infinite, even granular.

Along with Braxton and his reeds, the group constants are Taylor Ho Bynum playing cornets and trombone; tubist Dan Peck and harpist Jacqui Kerrod. Another harpist – there are three others – is always present; accordionist Adam Matlock appears on 11 of the pieces; cellist Tomeka Reid appears on eight; violinist Jean Cook on three; saxophonist Ingrid Laubrock and trumpeter Stephanie Richards figure in the nonet’s four performances. The harps, strings and accordion are key to the music’s special qualities: it is often sweeping, fluid and delicate, though those dreamlike and gentle textures mingle and fuse with the diverse sounds supplied by the winds. Braxton’s own alto saxophone can range from silky sweet to abrasive, and he also brings along instruments ranging from sopranino saxophone to contrabass clarinet.

Braxton provides extensive notes in an accompanying booklet, and they’re as rich and playful as the music, which can sound as natural as a convergence of streams in a pond: “the notated material is positioned on top of an ‘unstable metric gravity’. This is a ‘wobbly music architecture’.” This multiple and unpredictable movement defines the music, a brilliant confluence of composed and improvised elements, a sonic flux of such delicacy that rhythmic, tonal and timbral incongruities combine to suggest an immersion in the spirit of change.

Braxton has previously remarked that “I want the undefined component of my music to be on an equal par with the defined component,” and it’s a goal that he continues to extend here. If James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake is the most musical of books, Braxton’s ZIM is its double, diverging concordances passing over and through one another in a babbling dream discourse, free in some sense that music rarely is, as diverse in its methods as in its favoured sonorities, from those sibilant saxophones to brash brass blasts and hand-swept harp strings.

Whichever iteration of the group appears, the performance suggests it’s the ideal scale. As broad as the invention becomes, there’s always a sense of meaning rather than mere novelty, each event arising with its own certainty, however realized, an inevitability in accord with the logic of a dream, including a strange nonet passage in Composition No.415 in which Peck’s tuba wanders in a field of sudden pointillist punctuations from the other winds.

By the time the septet reaches the final performances at London’s Café OTO, the pieces have stretched past the 70-minute mark and the strange fusions, mergers and discontinuities are ever more fully realized, the group pressing further and further into new territories, all the way to brief and uncredited vocal outbursts. On Composition No.420, Braxton’s alto initially fuses with the accordion and two harps; later he matches his sopranino’s whistle with Cook’s violin, which can also suggest an erhu; Bynum’s cornet flutters on a carpet of strummed harps, then whispers while the harpists diverge, one maintaining conventions while the other becomes percussionist and guitarist, striking the frame, slapping chords and picking a sparse melody. At times there’s an aviary in Braxton’s horns, from goose squawk to piping sparrow, while Peck’s tuba emits a low frequency hum that seems momentarily electronic. Toward the end, anarchic near-New Orleans jazz explodes and a harp sounds like elastic bands.

Braxton’s ZIM is music of surprise. These are broad aural canvases in which the participants surprise themselves as well as one another, reaching toward a collective music that breeds in myriad individual encounters and in which close conversationalists will come to finish one another’s sentences – a saxophone’s phrase becoming an accordion’s. It’s the sound of recognition and empathy, one mind, like one sound, becoming another.

Editor’s Note: Stuart Broomer is the author of Time and Anthony Braxton (Toronto: The Mercury Press, 2009).

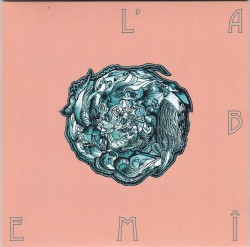

L’ABÎME

L’ABÎME