Editor's Corner - December 2022

You may have read Max Christie’s article “John Beckwith Musician” two issues ago (The WholeNote Volume 28/1) about the launch of Beckwith’s latest book Music Annals: Research and Critical Writings by a Canada Composer 1973-2014, and Christie’s sequel “Meanwhile back at Chalmers House” in the following issue. The evening of the launch at the Canadian Music Centre included a live performance by SHHH!! Ensemble and provided my first exposure to this duo from Ottawa: Zac Pulak (percussion) and Edana Higham (piano). Dedicated to performing and commissioning new works, their debut CD Meanwhile has recently been released by Analekta (AN 2 9139 analekta.com/en). Comprising works by five mid-career Canadian composers including Monica Pearce (whose leather was also included on that composer’s portrait disc Textile Fantasies reviewed in this column last month), Jocelyn Morlock, Kelly-Marie Murphy, Micheline Roi and John Gordon Armstrong, plus one relative newcomer on the scene, Iranian-Canadian Noora Nakhaie, and the current grand old man of Canadian music, Beckwith himself. All of the works were written for the pair, with the exception of Murphy’s Dr. Blue’s Incredible Bone-Shaking Drill Engine which was Pulak’s first commission back in 2016 “fresh out of school and out of my depth.” Murphy, who had never written for solo percussion, eagerly took on the project and created a dynamic and almost relentless work for unpitched drums with only a brief respite in metal and bell sounds. This is followed by Roi’s Grieving the Doubts of Angels, a motoric, minimal and mostly melodic work which ends dramatically with a pounding pulse.

You may have read Max Christie’s article “John Beckwith Musician” two issues ago (The WholeNote Volume 28/1) about the launch of Beckwith’s latest book Music Annals: Research and Critical Writings by a Canada Composer 1973-2014, and Christie’s sequel “Meanwhile back at Chalmers House” in the following issue. The evening of the launch at the Canadian Music Centre included a live performance by SHHH!! Ensemble and provided my first exposure to this duo from Ottawa: Zac Pulak (percussion) and Edana Higham (piano). Dedicated to performing and commissioning new works, their debut CD Meanwhile has recently been released by Analekta (AN 2 9139 analekta.com/en). Comprising works by five mid-career Canadian composers including Monica Pearce (whose leather was also included on that composer’s portrait disc Textile Fantasies reviewed in this column last month), Jocelyn Morlock, Kelly-Marie Murphy, Micheline Roi and John Gordon Armstrong, plus one relative newcomer on the scene, Iranian-Canadian Noora Nakhaie, and the current grand old man of Canadian music, Beckwith himself. All of the works were written for the pair, with the exception of Murphy’s Dr. Blue’s Incredible Bone-Shaking Drill Engine which was Pulak’s first commission back in 2016 “fresh out of school and out of my depth.” Murphy, who had never written for solo percussion, eagerly took on the project and created a dynamic and almost relentless work for unpitched drums with only a brief respite in metal and bell sounds. This is followed by Roi’s Grieving the Doubts of Angels, a motoric, minimal and mostly melodic work which ends dramatically with a pounding pulse.

A highlight for me is Nakhaie’s Echoes of the Past, inspired by Sister Language, a moving book by Martha and Christina Baillie. This testament to the triumphs and struggles experienced by a family dealing with profound mental illness and to the bond between siblings is sensitively interpreted by the composer. Meanwhile concludes with the title piece, the duo’s first commission, a 2018 work for marimba and piano (both inside and out) by Beckwith in which the then 91-year-old shows no signs of compromise in his approach. There are echoes of earlier works – Keyboard Practice comes to mind – yet we are left with the impression that the composer is looking forward as much as back. Forward is definitely the direction of SHHH!! Ensemble and we’re glad to be along for the ride.

Kelly-Marie Murphy reappears on the next disc, de mille feux (a million lights) featuring the Andara Quartet (leaf music LM262 leaf-music.ca). Murphy’s Dark Energy was commissioned by the Banff Centre and the CBC as the required work in the 2007 Banff International String Quartet Competition, won that year by Australia’s Tinalley String Quartet although the prize for best performance of the Canadian commission was awarded to the Koryo String Quartet (USA). The Andara Quartet would not be formed until seven years later when the members met at the Conservatoire de musique de Montréal. They have subsequently gone on to residencies at the Banff Centre, the Ottawa Chamberfest and the University of Montreal. The quartet’s debut disc opens with Benjamin Britten’s all too rarely heard String Quartet No.1 with its angelic opening high-string chorale over pizzicato cello before transitioning into a caccia-like Allegro vivo. The extended Andante calmo third movement eventually leads to a playful finale in which the strings seem to be playing tag. This is contrasted with Samuel Barber’s gorgeous Molto Adagio extracted from his String Quartet in B Minor Op.11. Of course we are familiar with this “Adagio for Strings” in its standalone string orchestra and a cappella choral versions, but I must admit to have mixed feelings about having it cherry-picked in the context of a string quartet recording. Generous as the disc’s 65-minute duration is, there was ample space available to have included the quartet’s outer movements as well (less than ten minutes between them), but that is a minor quibble. Murphy’s single-movement work is next up, opening forebodingly, as many of her works do, before changing mood abruptly to a rhythmic and roiling second half featuring abrasive chordal passages and Doppler-like effects. The final work, producer James K. Wright’s String Quartet No.1 “Ellen at Scattergood” is in four somewhat anachronistic movements. It could have been written a century ago, but is none the worse for that. A pastoral depiction of life at the cottage of a couple of friends, it was commissioned by the husband as a gift for wife Ellen.

Kelly-Marie Murphy reappears on the next disc, de mille feux (a million lights) featuring the Andara Quartet (leaf music LM262 leaf-music.ca). Murphy’s Dark Energy was commissioned by the Banff Centre and the CBC as the required work in the 2007 Banff International String Quartet Competition, won that year by Australia’s Tinalley String Quartet although the prize for best performance of the Canadian commission was awarded to the Koryo String Quartet (USA). The Andara Quartet would not be formed until seven years later when the members met at the Conservatoire de musique de Montréal. They have subsequently gone on to residencies at the Banff Centre, the Ottawa Chamberfest and the University of Montreal. The quartet’s debut disc opens with Benjamin Britten’s all too rarely heard String Quartet No.1 with its angelic opening high-string chorale over pizzicato cello before transitioning into a caccia-like Allegro vivo. The extended Andante calmo third movement eventually leads to a playful finale in which the strings seem to be playing tag. This is contrasted with Samuel Barber’s gorgeous Molto Adagio extracted from his String Quartet in B Minor Op.11. Of course we are familiar with this “Adagio for Strings” in its standalone string orchestra and a cappella choral versions, but I must admit to have mixed feelings about having it cherry-picked in the context of a string quartet recording. Generous as the disc’s 65-minute duration is, there was ample space available to have included the quartet’s outer movements as well (less than ten minutes between them), but that is a minor quibble. Murphy’s single-movement work is next up, opening forebodingly, as many of her works do, before changing mood abruptly to a rhythmic and roiling second half featuring abrasive chordal passages and Doppler-like effects. The final work, producer James K. Wright’s String Quartet No.1 “Ellen at Scattergood” is in four somewhat anachronistic movements. It could have been written a century ago, but is none the worse for that. A pastoral depiction of life at the cottage of a couple of friends, it was commissioned by the husband as a gift for wife Ellen.

This maiden voyage for the Andara Quartet with its warm and convincing performances bodes well for their future, and for chamber music in this country. I also note that the triennial Banff Competition is still going strong 30 years after its inauguration – the first prize winner in 2022 was the Isidore Quartet (USA) and the Canadian Commission Prize went to Quatuor Agate (France). This year’s required work was by Dinuk Wijeratne and it’s great to realize that all nine of the competing quartets from around the world have taken that new Canadian work into their repertoires. Even more exciting is when a young quartet like the Andara takes on an earlier competition’s work and gives it new life as they have done with Dark Energy.

Listen to 'de mille feux' Now in the Listening Room

Blue and Green Music features two string quartets by American composer Victoria Bond performed by the Cassatt String Quartet along with the song cycle From an Antique Land and the standalone song Art and Science, both featuring baritone Michael Kelly with Bradley Moore, piano (Albany Music TROY1905 albanyrecords.com). The title work takes its inspiration from a painting of the same name by Georgia O’Keeffe, in the words of the composer an “abstract study in motion, color and form, with the interplay of those two colors that dance with each other in graceful, sensuous patterns.” The four movements endeavour to represent that interplay, and to these ears succeed gracefully and gleefully in the final movement Dancing Colors. Art and Science takes its text from a letter which Albert Einstein wrote to the editor of a German magazine that the composer says “even though it was written as a letter, the organization of thoughts was startling. There was such logic […] and such a sense of form that it was as though Einstein had composed a poem….” More traditionally, From an Antique Land does use poetry, with Recuerdo and On Hearing a Symphony of Beethoven by Edna St. Vincent Millay bookending poems by Percy Bysshe Shelley and Gerard Manley Hopkins. The accompaniment in the final song cleverly incorporates echoes of the third movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Although texts are not provided in the booklet, there are synopses, and frankly, Kelly’s lyric baritone voicing is so well articulated that the words are clearly understandable.

Blue and Green Music features two string quartets by American composer Victoria Bond performed by the Cassatt String Quartet along with the song cycle From an Antique Land and the standalone song Art and Science, both featuring baritone Michael Kelly with Bradley Moore, piano (Albany Music TROY1905 albanyrecords.com). The title work takes its inspiration from a painting of the same name by Georgia O’Keeffe, in the words of the composer an “abstract study in motion, color and form, with the interplay of those two colors that dance with each other in graceful, sensuous patterns.” The four movements endeavour to represent that interplay, and to these ears succeed gracefully and gleefully in the final movement Dancing Colors. Art and Science takes its text from a letter which Albert Einstein wrote to the editor of a German magazine that the composer says “even though it was written as a letter, the organization of thoughts was startling. There was such logic […] and such a sense of form that it was as though Einstein had composed a poem….” More traditionally, From an Antique Land does use poetry, with Recuerdo and On Hearing a Symphony of Beethoven by Edna St. Vincent Millay bookending poems by Percy Bysshe Shelley and Gerard Manley Hopkins. The accompaniment in the final song cleverly incorporates echoes of the third movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Although texts are not provided in the booklet, there are synopses, and frankly, Kelly’s lyric baritone voicing is so well articulated that the words are clearly understandable.

Dreams of Flying was commissioned by the Audubon Quartet and Bond took the name of the ensemble as inspiration to create a piece about birds. The opening movements, Resisting Gravity and Floating are as their titles describe and set the stage for the playful and boisterous The Caged Bird Dreams of the Jungle, which, after a gentle opening becomes truly joyous, replete with chirps, whistles and cries as the birds of the jungle awake. The work and the CD end exuberantly with Flight, featuring rising motifs, high glissandi and repeating rhythmic patterns. Here, as throughout this entertaining disc, all the performers shine.

Listen to 'Blue and Green Music' Now in the Listening Room

After 20 years working alongside Robert Aitken you might be forgiven for thinking I’d have heard enough flute music to last a lifetime and indeed there are times when I have said that a little flute goes a long way. That sentiment notwithstanding I encountered a lovely disc this month that put the lie to that. Through Broken Time features Jennifer Grim in contemporary works for solo and multiple flutes, some with piano accompaniment provided by Michael Sheppard (New Focus Recordings FCR346 newfocusrecordings.com). I had put the disc on while cataloguing recent arrivals without paying undo attention until the bird-like sounds and Latin rhythms of Tania León’s Alma leapt out at me. I had just finished listening to Victoria Bond’s disc, and it was as if I were back in the jungle dreamed of by the caged bird mentioned above.

After 20 years working alongside Robert Aitken you might be forgiven for thinking I’d have heard enough flute music to last a lifetime and indeed there are times when I have said that a little flute goes a long way. That sentiment notwithstanding I encountered a lovely disc this month that put the lie to that. Through Broken Time features Jennifer Grim in contemporary works for solo and multiple flutes, some with piano accompaniment provided by Michael Sheppard (New Focus Recordings FCR346 newfocusrecordings.com). I had put the disc on while cataloguing recent arrivals without paying undo attention until the bird-like sounds and Latin rhythms of Tania León’s Alma leapt out at me. I had just finished listening to Victoria Bond’s disc, and it was as if I were back in the jungle dreamed of by the caged bird mentioned above.

I suppose it was inevitable that I would find Julia Wolfe’s Oxygen for 12 flutes (2021) reminiscent of Steve Reich’s Vermont Counterpoint for flute and tape or 11 flutes, which I first heard in Ransom Wilson’s multi-tracked recording some four decades ago I don’t mean to say that Wolfe’s work is derivative of that classic, but that the orchestra of flutes, in this case involving all the regular members of the flute family rather than Reich’s piccolos, C and alto flutes, and especially the consistency of sound from part to part as a result of them all being played by one flutist, has a familiarity, especially in the context of Wolfe’s post-minimalist style. The addition of bass flute to the mix fills out the wall of sound, the density of which can at times be mistaken for a pipe organ. The liner notes also liken the piece to Stravinsky’s Symphonies of Wind Instruments but whatever the forebears, Wolfe has made this flute choir her own and Grim rises to the occasion in spades.

David Sanford is represented by two jazz inspired works, Klatka Still from 2007, and Offertory (2021), the first a homage to trumpeters Tony Klatka and Tomasz Stanko, and the second inspired by the extended improvisations of John Coltrane and Dave Liebman. The disc also includes solo works by Alvin Singleton and Allison Loggins-Hull – this latter a haunting work that meditates on the devastation wreaked by hurricane Maria, social, political and racial turmoil in the United States, and the Syrian civil war – and Wish Sonatine by Valerie Coleman, a dramatic work that conveys brutality and resistance and which incorporates djembe rhythms symbolizing enslaved Africans. Grim proves herself not only comfortable but fluent in all the diverse idioms and the result is a very satisfying disc.

Listen to 'Through Broken Time' Now in the Listening Room

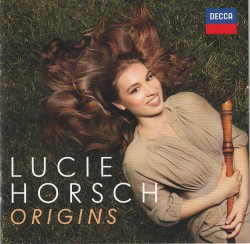

If Jennifer Grim’s CD can be considered diverse within the context of contemporary composition, Origins, featuring rising super-star recorder virtuoso Lucie Horsch, takes musical diversity to a whole ‘nother level (Decca 485 3192 luciehorsch.com). Most of the works are arrangements, opening with Coltrane’s classic Ornithology followed by Piazzolla’s Libertango. The accompaniments vary, ranging from orchestra and chamber ensemble to bandoneon, guitar, kora and, in Horsch’s own arrangement of Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances Sz.56, cimbalom (Dani Luca). There is an effective interpretation of Debussy’s solo flute masterpiece Syrinx and more Horsch arrangements of works by Stravinsky. Traditional material includes Simple Gifts and the Irish tunes She Moved Through the Fair and Londonderry Air. Like Grim with flutes, Horsch plays all the members of the recorder family and although I don’t see a bass there, she is pictured with five different instruments in the extensive booklet. At home in seemingly all forms of music, including such unexpected treats as improvisations on traditional Senegalese songs (with kora master Bao Sissoko) and one of contemporary composer Isang Yun’s demanding unaccompanied works, Horsch is definitely a young artist to watch.

If Jennifer Grim’s CD can be considered diverse within the context of contemporary composition, Origins, featuring rising super-star recorder virtuoso Lucie Horsch, takes musical diversity to a whole ‘nother level (Decca 485 3192 luciehorsch.com). Most of the works are arrangements, opening with Coltrane’s classic Ornithology followed by Piazzolla’s Libertango. The accompaniments vary, ranging from orchestra and chamber ensemble to bandoneon, guitar, kora and, in Horsch’s own arrangement of Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances Sz.56, cimbalom (Dani Luca). There is an effective interpretation of Debussy’s solo flute masterpiece Syrinx and more Horsch arrangements of works by Stravinsky. Traditional material includes Simple Gifts and the Irish tunes She Moved Through the Fair and Londonderry Air. Like Grim with flutes, Horsch plays all the members of the recorder family and although I don’t see a bass there, she is pictured with five different instruments in the extensive booklet. At home in seemingly all forms of music, including such unexpected treats as improvisations on traditional Senegalese songs (with kora master Bao Sissoko) and one of contemporary composer Isang Yun’s demanding unaccompanied works, Horsch is definitely a young artist to watch.

The final disc I will mention is the EP Water Hollows Stone, a compelling work for two pianos by American composer Alex Weiser (Bright Shiny Things BSTC-0176 brightshiny.ninja), which takes its title from a quotation by Ovid that the composer saw inscribed in Latin on the wall of a subway station in NYC. Performed by Hocket (pianists Sarah Gibson and Thomas Kotcheff) the three movements are Waves, a quietly roiling texture from which “phrase, melody and harmony” eventually emerge, Cascade, a series of rising and falling arpeggios based on “a misquotation” of one of Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations, and Mist, which uses “an evocative keyboard technique borrowed from Helmut Lachenmann “where the notes of a chord are released individually so that the decay is as important as the initial sounds.” It is a very effective technique, a kind of juxtaposition of positive and negative space, and it is further developed in Fade, a standalone piece for solo piano conceived as a postlude to the 18-minute Water Hollows Stone, performed here by Gibson. A very immersive disc.

The final disc I will mention is the EP Water Hollows Stone, a compelling work for two pianos by American composer Alex Weiser (Bright Shiny Things BSTC-0176 brightshiny.ninja), which takes its title from a quotation by Ovid that the composer saw inscribed in Latin on the wall of a subway station in NYC. Performed by Hocket (pianists Sarah Gibson and Thomas Kotcheff) the three movements are Waves, a quietly roiling texture from which “phrase, melody and harmony” eventually emerge, Cascade, a series of rising and falling arpeggios based on “a misquotation” of one of Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations, and Mist, which uses “an evocative keyboard technique borrowed from Helmut Lachenmann “where the notes of a chord are released individually so that the decay is as important as the initial sounds.” It is a very effective technique, a kind of juxtaposition of positive and negative space, and it is further developed in Fade, a standalone piece for solo piano conceived as a postlude to the 18-minute Water Hollows Stone, performed here by Gibson. A very immersive disc.

I began this article with a mention of John Beckwith’s Music Annals and I’d like to turn now to another book that documents an important moment in the cultural annals of Quebec. When Paul-Émile Borduas published his manifesto Refus Global in 1948 it was a harbinger of Quebec’s Quiet Revolution and the changes that would come in the following decades. The 16 signatories included artists, dancers and actors who were associated with the Automatiste movement, previously known as the Montreal Surrealists. Among them was the writer Claude Gauvreau (1925-1971) whose arcane and often invented language used “[s]craps of known abstract words, shaped into a bold unconscious jumble.”

I began this article with a mention of John Beckwith’s Music Annals and I’d like to turn now to another book that documents an important moment in the cultural annals of Quebec. When Paul-Émile Borduas published his manifesto Refus Global in 1948 it was a harbinger of Quebec’s Quiet Revolution and the changes that would come in the following decades. The 16 signatories included artists, dancers and actors who were associated with the Automatiste movement, previously known as the Montreal Surrealists. Among them was the writer Claude Gauvreau (1925-1971) whose arcane and often invented language used “[s]craps of known abstract words, shaped into a bold unconscious jumble.”

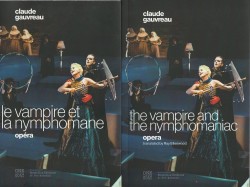

Toronto’s One Little Goat theatre company, in association with Nouvelles Éditions de Feu-Antonin, has just published the libretto of Gauvreau’s 1949 opera Le vampire et la nymphomane/The Vampire and the Nymphomaniac in a bilingual edition brilliantly translated by Automatiste scholar Ray Ellenwood (onelittlegoat.org/publications). Although Gauvreau originally planned to work with Pierre Mercure on the opera, that composer withdrew from the project and it was never realized during Gauvreau’s lifetime. The absurdist libretto – “A new concrete reality where music and meaning meet” – makes for difficult comprehension – “Gauvreau is marshalling his creative powers to explode the profundities of human consciousness…” – but simply put, in the words of the translator, it is “[a] love story. Star-crossed lovers kept apart by the forces of patriarchy: church, husband, police, psychiatry.”

“Gauvreau’s opera opens the possibility of a renewed push towards the purely sonic dimension of language.” In his own words “This work is vocal, purely auditory. […] It’s an opera exclusively for the ear […] not conceived with anything else in mind but music.” It was only after Serge Provost became interested in Le vampire et la nymphomane two decades after Gauvreau’s death – he first composed L’adorable verrotière using fragments from it in 1992 – that the opera began to take shape. In 1996 Montreal’s Chantes Libres presented the first production with baritone Doug MacNaughton and soprano Pauline Vaillancourt in the title roles and a supporting cast that included, among others, mezzo Fides Krucker and actors Albert Millaire and Monique Mercure, under the stage direction of Lorraine Pintal. Provost’s score was performed by the Nouvel Ensemble Moderne with founder Lorraine Vaillancourt at the helm. It is a striking production and thankfully it is available in its two-hour entirety on the Chants Libres website (chantslibres.org/en/videos). It is a perfect complement to this important new testament to the creative powers of Gauvreau, his unique voice in both the cultural history of Quebec and Canadian literature.

[Quotations are taken from the informative essays by Ray Ellenwood, Adam Seelig and Thierry Bissonnette which provide useful contextual information for Gauvreau’s opera in the One Little Goat publication.]

We invite submissions. CDs, DVDs and comments should be sent to: DISCoveries, WholeNote Media Inc., The Centre for Social Innovation, 503 – 720 Bathurst St. Toronto ON M5S 2R4.

David Olds, DISCoveries Editor

discoveries@thewholenote.com