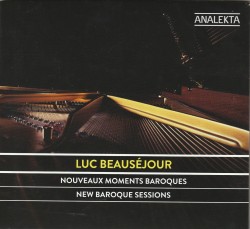

New Baroque Sessions - Luc Beauséjour

New Baroque Sessions

New Baroque Sessions

Luc Beauséjour

Analekta AN 2 8919 (analekta.com/en)

Solitary ways of existence brought on by the current pandemic have resulted in spurs of interesting solo projects around the world. Many performing artists have been contemplating the question of their artistic identity in the circumstances that extinguish the very nature of their art. A solo statement of a kind, New Baroque Sessions is an album that captures one artist’s way of retaining the essence of their creative expression while playing the music they love.

This second volume of Baroque music played on piano (the first one was published in 2016) is a collection of Luc Beauséjour’s favourite pieces from the Baroque repertoire. The compositions, by Bach, Couperin (Armand-Louis and François), Scarlatti, Fischer, Sweelinck, Froberger and Balbastre, touch upon different corners of vast Baroque treasures. Some are well known, others explored less often. All are predominantly written for harpsichord but translate exceptionally well to piano, which was one of Beauséjour’s intentions with this album.

A versatile performer, equally at home on harpsichord, organ and piano, Beauséjour has an elegance to his playing that is truly rare. Here is the performer that plays with colours and articulations; a performer of subtle gestures that amount to grand statements. The pieces themselves contain creative elements one does not necessarily expect – musical portraits, clever compositional techniques, tributes to Greek muses, or simple utterances of the resilience of their times. While honouring Baroque traditions, there is a touch of contemporaneity to Beauséjour’s interpretations, adding an incredible freshness to this album.