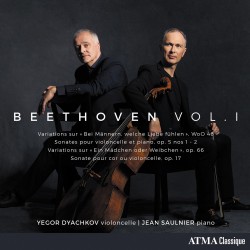

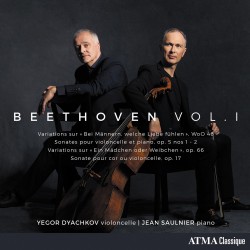

Beethoven Vol.1 is the initial digital release in a new series of the Complete Sonatas and Variations for Cello and Piano featuring cellist Yegor Dyachkov and pianist Jean Saulnier. The series will be launched in both digital and physical format, with the second digital volume available in September and a complete 3CD physical set due for release in October (ATMA Classique ACD2 4046 atmaclassique.com/en).

Beethoven Vol.1 is the initial digital release in a new series of the Complete Sonatas and Variations for Cello and Piano featuring cellist Yegor Dyachkov and pianist Jean Saulnier. The series will be launched in both digital and physical format, with the second digital volume available in September and a complete 3CD physical set due for release in October (ATMA Classique ACD2 4046 atmaclassique.com/en).

The central works on this first digital volume are the Cello Sonatas No.1 in F Major Op.5 No.1 and No.2 in G Minor Op.5 No.2. Both were written in late 1796, and mark the beginning of Beethoven’s development of the cello and piano sonata as an equal partnership.

The two sets of variations are both on themes from Mozart’s The Magic Flute: the 12 Variations on “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen” Op.66 and the 7 Variations on “Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen” WoO46. The Horn Sonata in F Major Op.17, in the cello version prepared by Beethoven himself, closes the disc.

Dyachkov is a professor at McGill’s Schulich School of Music, and he and Saulnier both teach at the Université de Montréal. Their performances here are intelligent and beautifully nuanced, promising great things for the works still to be released.

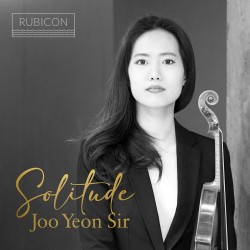

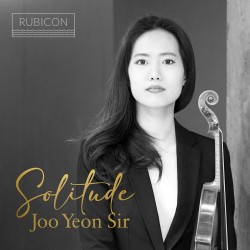

When the COVID lockdown started, the London-based Korean violinist Joo Yeon Sir took the opportunity to explore the solo violin repertoire. Old and new works are equally represented on the resulting CD Solitude (Rubicon Classics RCD1076 rubiconclassics.com).

When the COVID lockdown started, the London-based Korean violinist Joo Yeon Sir took the opportunity to explore the solo violin repertoire. Old and new works are equally represented on the resulting CD Solitude (Rubicon Classics RCD1076 rubiconclassics.com).

Biber’s remarkable Passacaglia in G Minor opens the disc, followed by two of the Paganini Caprices Op.1 – No.10 in G Minor and No.24 in A Minor – and Kreisler’s Recitative and Scherzo-Caprice Op.6.

Sir is also a composer, and her My Dear Bessie from 2018 leads a group of four contemporary works, the others being Roxanna Panufnik’s Hora Bessarabia, Fazil Say’s Cleopatra Op.34 and Laura Snowdon’s Through the Fog, written for this CD. Ysaÿe’s Sonata No.6, Op.27 ends an excellent recital.

Sir has a big, strong tone and shows full command in a range of technical challenges.

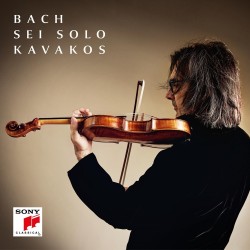

This is more of a belated notification of availability than a review, unfortunately, but due to a confusing digital link I was only able to listen to three complete works plus assorted movements from the Leonidas Kavakos release of the complete Sonatas & Partitas on Bach Sei Solo (Sony sonyclassical.com/releases/releases-details/bach-sei-solo).

This is more of a belated notification of availability than a review, unfortunately, but due to a confusing digital link I was only able to listen to three complete works plus assorted movements from the Leonidas Kavakos release of the complete Sonatas & Partitas on Bach Sei Solo (Sony sonyclassical.com/releases/releases-details/bach-sei-solo).

Still, the warm tone, traditional – almost Romantic – approach, rhythmic freedom, judicious ornamentation, leisurely triple and quadruple stops and resonant recording make it clear that this is a notable addition to the discography.

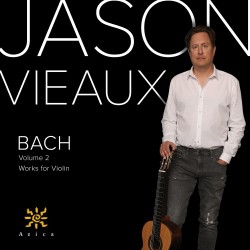

After a gap of 13 years the American guitarist Jason Vieaux has finally released Bach Vol.2: Works for Violin, completing his Bach cycle that started with three lute suites on Vol.1: Works for Lute. The works here are the Partita No.3 in E Major BWV1006 (which is also Lute Suite No.4), the Sonata No.3 in C Major BWV1005 and the Sonata No.1 in G Major BWV1001 (Azica ACD71347 jasonvieaux.com/music).

After a gap of 13 years the American guitarist Jason Vieaux has finally released Bach Vol.2: Works for Violin, completing his Bach cycle that started with three lute suites on Vol.1: Works for Lute. The works here are the Partita No.3 in E Major BWV1006 (which is also Lute Suite No.4), the Sonata No.3 in C Major BWV1005 and the Sonata No.1 in G Major BWV1001 (Azica ACD71347 jasonvieaux.com/music).

From the opening bars of the Partita it’s clear that this is going to be something very special: faultlessly clean technique and a full, rich, warm tone, all beautifully recorded with a resonant clarity.

“I always try to just play what’s there;” says Vieaux, “the difficult thing with Bach’s music on guitar is that there’s so much ‘there’ there.” He is fully aware of how interpretation can change and deepen as the years go by, and says “I hope you will enjoy this latest snapshot of where I’m at on that particular journey.”

“Enjoy” is an understatement; these are performances that get to the heart of this extraordinary music on an outstanding CD.

Jason Vieaux is also the sensitive accompanist for all but three of the 14 outstanding tracks on Shining Night, the latest CD from violinist Anne Akiko Meyers; Fabio Bidini is the pianist on the other three tracks (Avie AV2455 avie-records.com/releases).

Jason Vieaux is also the sensitive accompanist for all but three of the 14 outstanding tracks on Shining Night, the latest CD from violinist Anne Akiko Meyers; Fabio Bidini is the pianist on the other three tracks (Avie AV2455 avie-records.com/releases).

Described as an album that embraces themes of love, poetry and nature, the disc spans music from the Baroque era through to the contemporary scene. Vieaux is the partner on Corelli’s La Folia, Bach’s Air on G, Paganini’s Cantabile, the achingly lovely Aria from Villa-Lobos’ Bachianas Brasileiras No.5, Duke Ellington’s In My Solitude, Piazzolla’s complete four-movement Histoire du Tango, the Elvis Presley song Can’t Help Falling In Love and Leo Brouwer’s ode to the California giant sequoia trees Laude al Árbol Gigante.

Bidini accompanies Meyers on the Heifetz arrangement of Ponce’s beautiful Estrellita and on Dirait-On and Sure On This Shining Night, the two Morten Lauridsen pieces that close the CD. Meyers is in her usual superb form throughout a recital that is an absolute delight from start to finish.

Entre dos almas – Between two souls – features the music of the Spanish guitarist and composer Santiago de Murcia (1673-1739) in performances by Stefano Maiorana on Baroque guitar (Arcana A484 stefanomaiorana.it).

Entre dos almas – Between two souls – features the music of the Spanish guitarist and composer Santiago de Murcia (1673-1739) in performances by Stefano Maiorana on Baroque guitar (Arcana A484 stefanomaiorana.it).

The two souls are Spanish and Italian, the latter especially representing the influence of Arcangelo Corelli in Madrid. The two major works here are both Murcia’s transcriptions of Corelli: the Sonata in E Minor from Op.5 Nos.5 & 8; and the Sonata in C Major Op.5 No.3. Only the first and last movements of the latter survive, so Maiorana has supplied his own transcriptions of the middle three.

The eight individual pieces are an absolute delight, with a lively opening Fandango and a terrific Tarantelas particular highlights. Maiorana plays with an effortless technique and with complete freedom in a beautiful but quite different sound world that is just bursting with life. Some additions and arrangements are apparently by Maiorana, but his experience renders them completely undetectable.

Another quite different sound world – this time five-string banjo – is to be found on John Bullard Plays 24 Preludes for Solo Banjo by Adam Larrabee, Volume One Books 1 & 2 Nos. I-XII (Bullard Music johnbullard.com/music).

Another quite different sound world – this time five-string banjo – is to be found on John Bullard Plays 24 Preludes for Solo Banjo by Adam Larrabee, Volume One Books 1 & 2 Nos. I-XII (Bullard Music johnbullard.com/music).

Dedicated to developing and transcribing classical repertoire for the five-string banjo, Bullard commissioned Larrabee to write 24 preludes, which the composer says “follow the long-standing tradition of writing pieces in all the major and minor keys to showcase an instrument’s versatility.” The major keys here are C, D, E, F-sharp, A-flat and B-flat; the minor keys are A, B, C-sharp, E-flat, F and G. Each Prelude has a title – Dialogue, Jig, Barcarolle, Impromptu, Waltz, etc. – with the A-flat Major Cakewalk a particular standout.

I don’t know what astonishes me more – that someone could write these pieces or that someone can play them. They’re simply terrific – as indeed is Bullard. Volume Two eagerly awaited!

Keeping the “different sound world” theme going, The Mandolin Seasons – Vivaldi, Piazzolla features Jacob Reuven on mandolin and his boyhood friend Omer Meir Wellber playing accordion and harpsichord as well as conducting the Sinfonietta Leipzig, 18 string players drawn from the Gewandhaus Orchestra (Hyperion CDA68357 jacobreuven.com).

Keeping the “different sound world” theme going, The Mandolin Seasons – Vivaldi, Piazzolla features Jacob Reuven on mandolin and his boyhood friend Omer Meir Wellber playing accordion and harpsichord as well as conducting the Sinfonietta Leipzig, 18 string players drawn from the Gewandhaus Orchestra (Hyperion CDA68357 jacobreuven.com).

Each of the Vivaldi Four Seasons is followed by the appropriate season from Piazzolla’s Las cuatro estaciones porteñas, the four Buenos Aires pieces written between 1965 and 1970 and heard here in arrangements based on Leonid Desyatnikov’s orchestral adaptation. Each of the Piazzolla pieces contains direct quotes from the relevant Vivaldi concerto, so the pairings here feel perfect. The influence goes both ways, too – the Vivaldi concertos feature improvised accordion as well as harpsichord continuo.

Reuven displays dazzling dexterity and technique in beautifully atmospheric and effective performances, Wellber’s accordion adding a new and never intrusive dimension to the Vivaldi.

“A magical and fascinating sound world,” say my notes. Indeed it is.

If you prefer your Vivaldi Four Seasons in more traditional format then it’s hard to imagine better performers than I Musici, who made their debut in Rome in March 1952 and their first landmark recording of the work in 1955, just eight years after the 1947 recording by American violinist Louis Kaufman that launched the Vivaldi revival. Six more versions would follow between 1969 and 2012. The group marks the 70th anniversary of that first concert with the release of a new recording of Vivaldi, Verdi: Le Quattro Stagioni – The Four Seasons (Decca 4852630 deccaclassics.com/en/catalogue/products/the-four-seasons-i-musici-12623).

If you prefer your Vivaldi Four Seasons in more traditional format then it’s hard to imagine better performers than I Musici, who made their debut in Rome in March 1952 and their first landmark recording of the work in 1955, just eight years after the 1947 recording by American violinist Louis Kaufman that launched the Vivaldi revival. Six more versions would follow between 1969 and 2012. The group marks the 70th anniversary of that first concert with the release of a new recording of Vivaldi, Verdi: Le Quattro Stagioni – The Four Seasons (Decca 4852630 deccaclassics.com/en/catalogue/products/the-four-seasons-i-musici-12623).

Marco Fiorini, whose mother was a founding member of I Musici is the soloist in sparkling performances of the Vivaldi, paired here with the world-premiere recording of Verdi’s work of the same name, the ballet music from his 1855 opera I Vespri Siciliani, arranged for piano and strings by composer-pianist Luigi Pecchia.

Violin Odyssey, the latest CD from violinist Itamar Zorman is the result of his 2020 livestream video series Hidden Gems, another COVID lockdown project which featured lesser-known and rarely played works; ten were chosen for this album. Piano accompaniment is shared by Ieva Jokubaviciute and Kwan Yi (First Hand Records FHR119 firsthandrecords.com).

Violin Odyssey, the latest CD from violinist Itamar Zorman is the result of his 2020 livestream video series Hidden Gems, another COVID lockdown project which featured lesser-known and rarely played works; ten were chosen for this album. Piano accompaniment is shared by Ieva Jokubaviciute and Kwan Yi (First Hand Records FHR119 firsthandrecords.com).

The two major works are the 1917 Violin Sonata No.2 in B-flat Minor Op.43 by Dora Pejačevič and the 1927 Sonata No.2 by Erwin Schulhoff, both terrific works. The eight short pieces of the Heifetz arrangement of Joseph Achron’s Children’s Suite Op.57 are here, and there are short pieces by Grażyna Bacewicz, Moshe Zorman, Silvestre Revueltas, Ali Osman, Gao Ping and William Grant Still. Gareth Farr’s 2009 Wakatipu for solo violin is a brilliant highlight.

Zorman displays his customary strong, impassioned playing throughout an excellent disc.

Rebecca Clarke Works for Viola, featuring the French violist Vinciane Béranger with pianist Dana Ciocarlie is another addition to the growing body of recordings acknowledging the significance of the English viola virtuoso’s contribution to the viola repertoire (Aparté AP289 apartemusic.com).

Rebecca Clarke Works for Viola, featuring the French violist Vinciane Béranger with pianist Dana Ciocarlie is another addition to the growing body of recordings acknowledging the significance of the English viola virtuoso’s contribution to the viola repertoire (Aparté AP289 apartemusic.com).

The major work here is clearly the outstanding Viola Sonata from 1919, a passionate reading of which opens the disc. It’s followed by another early work, Morpheus from 1917-18 and the Passacaglia on an Old English Tune, from 1941.

Cellist David Louwerse joins Béranger for the Two Pieces for Viola and Cello from 1918 and the Irish Melody (Emer’s Farewell to Cucullain “Londonderry Air”) from c.1918, the latter only rumoured to exist until being discovered in the Royal Academy of Music in 2015 and published in 2020; this is its world-premiere recording.

Hélène Collerette is the violinist for the Dumka for Violin, Viola and Piano from 1941; the mostly pizzicato Chinese Puzzle for viola and piano from 1922 completes a fine CD.

Two of the Clarke pieces, plus two tracks from the Shining Night CD turn up on Adoration – Music of the Americas, a CD by the Brazilian violist Amaro Dubois with pianist Tingting Yao (Spice Classics amarodubois.com).

Two of the Clarke pieces, plus two tracks from the Shining Night CD turn up on Adoration – Music of the Americas, a CD by the Brazilian violist Amaro Dubois with pianist Tingting Yao (Spice Classics amarodubois.com).

Two works by Florence Price, the lovely title track and Fantasy in Purple, open the disc. The six Rebecca Clarke pieces include Chinese Puzzle and the Passacaglia, the latter drawing particularly strong playing from both performers. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s beautiful Five Songs of Sun and Shade show Dubois’ rich, warm tone at its best, and are real gems.

Some of the works in the second half of the CD are perhaps not quite as impressive, Piazzolla’s Libertango and the haunting Café 1930 from Histoire du Tango being followed by a not particularly successful transcription of Villa-Lobos’ Aria from Bachianas Brasileiras No.5, the very short Suite Nordestina by the Brazilian César Guerra-Peixe and Fanny Mendelssohn’s Six Lieder Op.7.

Dubois has a lovely tone across the full range of his instrument. Yao’s playing is fine, although the piano sound should really have a lot more depth and body. Dubois says that a second release of works for viola and piano by Latin American composers is scheduled for release in July.

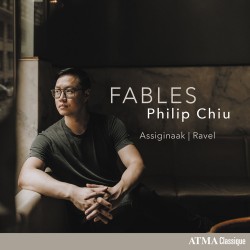

Fables – Maurice Ravel; Barbara Assiginaak

Fables – Maurice Ravel; Barbara Assiginaak