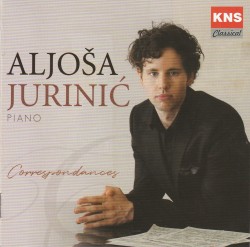

Correspondances - Aljoša Jurinić

Correspondances

Correspondances

Aljoša Jurinić

KNS Classical KNS A/097 (knsclassical.com)

The professional relationship of Chopin and Schumann was a curious one. Both composers were born in the same year, and while Schumann greatly praised the music of his Polish colleague, Chopin rarely, if ever, responded with similar sentiment. Whatever dissimilarities the two may have had, the Schumann Fantasy Op.17 and Chopin’s set of 12 Etudes Op.25 make a formidable pairing on this KNS live recording featuring Croatian-born pianist Aljoša Jurinić who came to Toronto in 2019.

To say the least, Jurinić’s credentials are impressive. Not only was he the winner of the Schumann Piano Competition in 2012, a laureate of the Queen Elisabeth and Leeds competitions in 2016, but also a finalist in the International Chopin competition in 2015. He has since appeared at Carnegie Hall, the Wiener Musikverein and the Tokyo Opera City Concert Hall.

The Fantasy is regarded as one of Schumann’s finest compositions and among the greatest in the entire Romantic repertoire. With its contrasting rhythms and tempi, the piece is not easy to bring off, but Jurinić’s performance is nothing less than sublime. He approaches the score with a true sense of grandeur, the broad sweeping lines of the opening, the stirring second movement and the introspective finale tempered with a flawless technique.

In the set of Chopin Etudes Jurinić breathes new life into this familiar repertoire, once again demonstrating full command of the technical challenges; from the graceful first etude in A-flat Major right to the thunderous No.12 which brings the set, and the disc, to a most satisfying conclusion.

How fortunate for Toronto that an artist of Jurinić’s stature has chosen to settle here – we can only hope his residency will be a lengthy one and that we may hear him perform in concert when conditions allow.