Pianos are Orphans

I've often thought: "How do I explain what the problem with pianos is – the neglect and abuse they suffer – to a non-pianist or even a non-musician? Here's my take on the problem...

I've often thought: "How do I explain what the problem with pianos is – the neglect and abuse they suffer – to a non-pianist or even a non-musician? Here's my take on the problem...

If one thinks of a plumber, a carpenter, ophthalmologist, chef or any other skilled tradesperson or professional, we all understand that they are only as good as their tools allow. Surgeons keep their scalpels sharp (we hope).

Professional musicians are no different. String players tune their instruments, they service the various parts, and they are responsible for their sound. They have professional craftspeople service what they themselves cannot. Reed players go through boxes of reeds trying to find one they can live with. They are very motivated to do justice to their craft, in an effort to transcend the craft and make it art. If a pad on a flute is loose, it's repaired. Musicians know what they need to do to make themselves and the music sound its best. They are responsible. They keep their tools sharp. If they sound like crap it's their fault. Moreover, everyone knows it.

With all that in mind, let's consider the pianist and his chosen tool. The pianist is completely dependent on a highly trained craftsperson-artist to even tune his instrument.

This job alone takes at least an hour and a half, even if the piano is co-operating. Which they rarely do because: 1] The piano may not have been tuned for months or even years! 2] It's been sitting near a heat source! 3] It's been in a bay window with freezing windows and then the hot sun shining on it for years. 4] There's no climate control. 5] It's been treated like a piece of furniture, not a highly complex musical instrument. Drinks have been spilled on it, in it. etc.

Pianos are complex machines, with parts that wear out. Contrary to popular belief, they don't improve with age! They are kind of like people: after about 80 years, they are pretty much done, unless they are completely rebuilt. The action (the parts that make each hammer move) needs to be regulated. Want to see how complex this is? Go to http://community.middlebury.edu/~harris/piano.regulation.pdf.

It's enough to know that the level of adjustment we're talking about here is on the order of tolerances of thousandths of an inch. I won't even discuss voicing the hammers. Suffice to say, many books have been written about these technical matters.

At any rate, let's consider this. A piano is bought for a room in a hotel, or a restaurant. Who's responsible for it? Who knows?

The piano starts off sounding pretty good, but only the pianists who play it really know how it feels and have the ears to judge its tuning and tone. During the first decade the piano is played by many pianists, hundreds of them, good and bad. Some are children who pound on the thing. Probably dozens of piano technicians have tuned the thing. Likely not one of them has even suggested an action regulation or voicing; why bother, obviously nobody cares about this instrument. The owners wouldn't know the difference – they can't even tell if it's in tune it or not!

Professional pianists might say something about maintaining the piano to venue management, but they never know who the technician is and have never spoken to the technician/tuner about that one note that keeps sticking or a thousand other possible problems. Besides, the pianist is being paid by the venue, why make waves? It might cost him a gig. Oh, he's got to run to another gig anyway. Let the next piano player suffer through that little problem.

At some point the manager of the room changes. People move on, the piano players change.Generations of people have careers, live and die. But the piano is always there – ignored, except for being occasionally played and then cursed.

Decades later, the venue (for example the King Edward Hotel) renovates, installing new marble floors, new wallpaper, new plumbing, new bathroom fixtures, spending 50 million bucks. But it's a different story for that beaten down brown baby grand with the hundreds of drinks spilled over the pin block, and a soundboard that has never been cleaned, that they paid $500.00 for in 1940. That piece of furniture, they need to keep; without having spent a dollar more the obligatory yearly tuning. (Which is insufficient in this climate.)

For years pianists sit down at this thing, and the best of them figure out how to play around the problems. Their own professionalism smooths out the obvious problems, and to the layperson/causal listener they sound pretty good, and so does the piano. So when one of these concerned pianists (after sweating bullets for three hours trying to tame this beast) finally gets the gumption to say something to the management about the sorry state of the piano, his own skill has undermined his position.

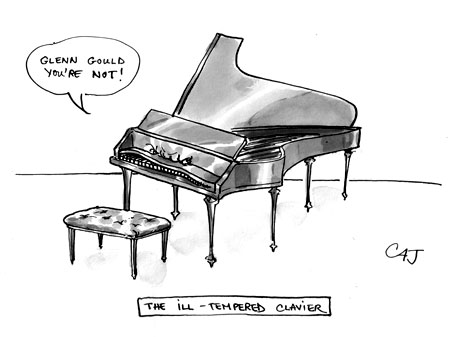

Venue management says: "Sounds fine to me." Or "Sheesh, who does he think he is, Glenn Gould?" (As if one of these venue managers would even know who Glenn Gould was.)

Where was I?

It's obvious that the pianist and the tuner are the only people who can say anything about the state of the piano. But (and it's a big but) they are paid by management – and unlike the other musicians discussed above, don't own the instrument or its problems. No one is responsible to it, and for it. The only people who can speak to its condition have a great incentive to keep their respective mouths shut. After all, managers don’t want to hear about something that will just cost them money, especially when they can't hear the difference. Aural memory is one of our most ephemeral memories. That's why we listen to loudspeakers in the same room, one right after the other, when we comparison shop.)

You can see the problem. A piano in a public venue is an orphan. It's not just an orphan. It's a poor neglected, abused, fetal alcohol syndrome, crack baby that grows into one pathetic old beast that can break your heart.

So it’s no surprise when, after 60 or 70 years of this, the venue manager says to the whisper of complaint: "What's wrong with the piano? No one else has complained about it!"

Venue managers somehow think pianos (because they do last for decades) could last for who knows how long. It seems infinite. We're fast approaching the end of the lives of all the pianos that were made in the 50s 60s and 70s. But somehow the people who have these pianos think that they should, like Old Man River, "Just Keep Rollin' Along."

The irony is that these days, if a pianist has the intestinal fortitude to say anything, and is successful in convincing a venue manager that something must be done, the venue will probably not fix the piano, but get rid of it and not replace it. The venue will then expect to have all the piano players bring their keyboards, (poor imitations of a decent acoustic piano at best), and not pay any more for the fact that pianists have now let them off the hook for presenting music respectfully. The pianists will have absolved the venue of any responsibility to do justice to the music that they are presenting.

And in advance of the inevitable responses that electronic keyboards are the answer, I say not for me – not if you're serious about being a piano player! Ultimately, pianists would prefer to play the real deal if possible. However, to make a living, and play at all, many are forced to accept this option. Don't kid yourself; most piano players aren't thrilled with this "choice."