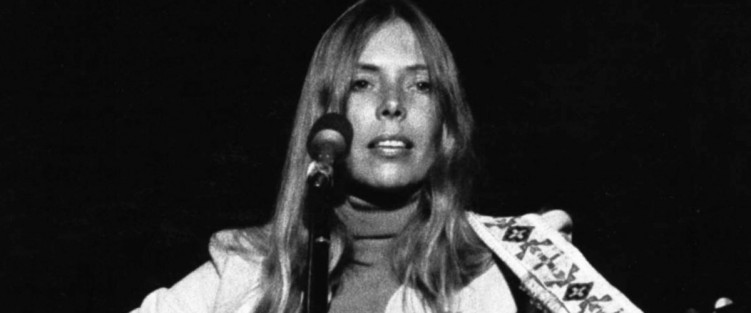

I’m not sure I’m entirely surprised that it was a Canadian who wrote “Don’t it always seem to go/That you don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone.” Joni Mitchell’s 1970 lament for the loss of a bit of Hawaiian landscape has taken on new meaning in our pandemic-roiled lives some 50 years later. Today, lamenting what has gone, temporarily or not, has become a worldwide emotionally traumatic phenomenon.

I’m not sure I’m entirely surprised that it was a Canadian who wrote “Don’t it always seem to go/That you don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone.” Joni Mitchell’s 1970 lament for the loss of a bit of Hawaiian landscape has taken on new meaning in our pandemic-roiled lives some 50 years later. Today, lamenting what has gone, temporarily or not, has become a worldwide emotionally traumatic phenomenon.

But so has its reverse – being aglow in anticipation of what might return. That’s certainly how I’ve felt as I’ve eagerly devoured the announcements of what’s planned for the upcoming season for many of the major musical institutions in the city. It’s true – the bogey of the variants has taught us that our expectation of a clear, straight-line recovery from our own black plague is not to be. The future is considerably less than clear for performing arts organizations. Nonetheless, the desire to move forward, to plan, to anticipate the future, such a uniquely human characteristic, is on full display in our musical institutions.

The pandemic has been something of a litmus test for many organizations and institutions in society, testing their durability and persistence, and our musical institutions are no different. Some have struggled to keep the faith, and maintain their identity. Others have refused to let the incredible circumstances of the past 18 months dim their normal creativity. And for a very few, the pandemic has actually made them more creative than ever – among them two organizations in our community one might not have expected to do so: Tafelmusik and The Royal Conservatory of Music.

I have long been a great fan of Tafelmusik, so their ability to remain current and contemporary and relevant is not such a surprise, even though their chosen repertoire would seem inclined to trap them in a musical culture long past. Not in the slightest. Under their late, deeply lamented music director, Jeanne Lamon, Tafelmusik always pushed every kind of boundary. That’s even more the case under their current leader, the deeply talented and immensely creative Elisa Citterio. One of the great tragedies of COVID for me has been its robbing of Citterio of the creative momentum she had just started to establish with Tafelmusik when the virus hit last year.

No matter. Tafelmusik is surging ahead this season: finally presenting Citterio’s new orchestral arrangements of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, which has been planned, and delayed, for two years, and continuing to boldly go where few Baroque orchestras have gone before, deep into the repertoire of the 19th century. Following their immensely successful Tchaikovsky concert of two years ago, they are back with another, this one devoted to Antonin Dvořák. Also, while bassist Alison Mackay has retired from the orchestra, the torch of her genius in creating Tafelmusik’s famed multimedia events is still alive, taken up in the season ahead by oboist Marco Cera and magician Nick Wallace in a show exploring the connection between these two famously dark arts.

Then there’s the Tafelmusik Chamber Choir, one of the great gems of the country, celebrating its 40th anniversary this season with, among other things, a presentation of the Everest of Baroque choral works, Bach’s B-Minor Mass, conducted not by the Choir’s own Ivars Taurins, but by one of the great Bach interpreters of our generation, Masaaki Suzuki. It is a function of Taurins’ grace, I think, that he has relinquished the podium on this special occasion. (Full disclosure: Ivars and I are friends; we have happily collaborated on three fine programs for CBC Radio’s Ideas). But make no mistake about it – and it’s not just friendly bias speaking – Taurins is one of the finest, and unfairly underrated, conductors in all of North America. (Check out the virtual Jesus bleibet meine Freude the Choir just posted if you need more proof – light and energetic, a revelation). The Choir’s 40th anniversary season is well worth celebrating.

But the real surprise for me in the spate of new programming announcements made recently was the season just unveiled by The Royal Conservatory of Music. Mervon Mehta has been running the Conservatory’s Koerner Hall programming admirably for many years now, but recently he has added considerably more original events to his mix. That began with the highly successful 21C New Music Festival he began seven years ago, so much more important now since the TSO dropped their New Creations Festival. But this season, the Conservatory has a wealth of exciting concerts, beginning with their star-studded gala performance of Stephen Sondheim’s Follies in Concert, certain to be an unforgettable evening in the concert hall (as was the original in the 80s). Then, there’s Gould’s Wall, a new Brian Current multimedia opera project co-presented with Tapestry Opera, bringing the spirit of Glenn Gould into the 21st century. There are concerts from pianists Seong-Jin Cho and the amazing Vikingur Ólaffson. There’s a performance of Ana Sokolović’s wonderful a cappella mini-opera, Svadba, the music of Miles Davis interpreted by Indian musicians, and many, many other wonderful concerts, topped off by the first visit of Swedish mezzo Anne Sofie von Otter to Toronto in half a dozen years. A truly exciting schedule.

But the real surprise for me in the spate of new programming announcements made recently was the season just unveiled by The Royal Conservatory of Music. Mervon Mehta has been running the Conservatory’s Koerner Hall programming admirably for many years now, but recently he has added considerably more original events to his mix. That began with the highly successful 21C New Music Festival he began seven years ago, so much more important now since the TSO dropped their New Creations Festival. But this season, the Conservatory has a wealth of exciting concerts, beginning with their star-studded gala performance of Stephen Sondheim’s Follies in Concert, certain to be an unforgettable evening in the concert hall (as was the original in the 80s). Then, there’s Gould’s Wall, a new Brian Current multimedia opera project co-presented with Tapestry Opera, bringing the spirit of Glenn Gould into the 21st century. There are concerts from pianists Seong-Jin Cho and the amazing Vikingur Ólaffson. There’s a performance of Ana Sokolović’s wonderful a cappella mini-opera, Svadba, the music of Miles Davis interpreted by Indian musicians, and many, many other wonderful concerts, topped off by the first visit of Swedish mezzo Anne Sofie von Otter to Toronto in half a dozen years. A truly exciting schedule.

Not everything musical is rosy in our post-pandemic world, however. The uncertainty engendered by the pandemic has dangers as well as opportunities, and the institution I fear for most in this regard is the Toronto Symphony. OK, fear is maybe too strong a word. But for 12 years, from 2001 to 2013, the TSO had one president and CEO, Andrew Shaw. Since then, it has had four more. The disgraced Jeff Melanson from 2014 to mid-2016. Then six months of board member Sonia Baxendale. Then two years or so of Gary Hanson. Then what was supposed to be a long-term solution, Matthew Loden. Except that Loden abruptly announced his resignation from the position in July after only three years in the job. The TSO is now looking for his replacement.

That’s like a baseball team having five different club presidents in seven years: it’s not healthy, it’s not good for an institution trying to meet new and unprecedented artistic challenges. However, the TSO has proven remarkably resilient in the past, and will likely do so again. Because of an amazingly generous and saintly gift from the Beck family (Thomas Beck was a longtime TSO chair of the board; his daughter occupies that position today), the TSO’s finances are in much better shape than you might expect. They have a “new” musical director, Gustavo Gimeno, or should have, although the pandemic has delayed his true arrival here for over a year.

That being said, the TSO is refusing to be undone by the many issues it faces. While the TSO’s 2021/22 season lacks enormous blockbusters, there are some very encouraging signs within their concert programs. Virtually every concert of the season includes some contemporary music, and not just the inevitable seven-minute opening piece, programmed to score some Canada Council grant. Instead, significant works, from talented composers like Joan Tower, Vivian Fung, Caroline Shaw and Missy Mazzoli and several Canadian commissions and premieres are on TSO programs, including a new work commissioned from Zosha Di Castri for soprano Barbara Hannigan, and a slew of works throughout the season by Canadian composer Samy Moussa, the orchestra’s artist-in-residence.

On the more conventional side, the TSO is presenting a concert of Bach and Mozart featuring and conducted by Angela Hewitt; James Ehnes is playing the Beethoven concerto with Andrew Davis leading the band, and an all-Bach concert led by Jonathan Crow looks especially interesting. Despite everything, or perhaps because of everything, the desire to create and connect remains active within the TSO as it commences the celebration of its 100th anniversary season.

I haven’t noted everything that’s planned for the fall, including ambitious projects by Opera Atelier and the COC (especially their presentation of a Mozart Requiem conceived by Against the Grain’s Joel Ivany and the COC’s Johannes Debus). But I can feel a sense of anticipation that follows such a long period of intense deprivation as keenly as I’ve ever looked forward to any musical experience. Maybe in the end, despite all the dislocation and pain, Joni Mitchell will have written the last word on our love of music – that only when we lost it did we realize how profoundly important it is. Except, if we’re lucky, we’re getting it back.

Robert Harris is a writer and broadcaster on music in all its forms. He is the former classical music critic of The Globe and Mail and the author of the Stratford Lectures and Song of a Nation: The Untold Story of O Canada.Story of O Canada.

Story revised 2021-09-27 to accurately state the number of years Matthew Loden was CEO of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra.