One of the more unfortunate things about the pandemic, in my biased opinion, has been the lost opportunity we Canadians have had to say a proper goodbye – goodbye and thank you – to Alexander Neef. Neef, who ran the Canadian Opera Company for 12 years, actually slipped out of town last fall during the pandemic and officially took up his duties at the Paris Opera in February. Since then, he has emerged as one of the boldest artistic directors in the world.

One of the more unfortunate things about the pandemic, in my biased opinion, has been the lost opportunity we Canadians have had to say a proper goodbye – goodbye and thank you – to Alexander Neef. Neef, who ran the Canadian Opera Company for 12 years, actually slipped out of town last fall during the pandemic and officially took up his duties at the Paris Opera in February. Since then, he has emerged as one of the boldest artistic directors in the world.

First, he shocked the intellectual complacency of France by daring to set the companies and administration of the Paris Opera on a thoroughly modern course of social equity and inclusiveness.

Then, he surprised the world again, this time in the artistic sphere, by hiring Gustavo Dudamel to be the music director of the Opera for the next five years, the expected choice of, it seems, no one. Both were provocative acts of artistic gutsiness and bravado, part and parcel of a man we hardly got to know while he was here. Hardly got to know, and (gauging by some of the chatter I’ve read and heard about Neef over the years) weren’t entirely sure we approved of. I guess it shouldn’t surprise me anymore, because this is Canada after all, and artistic success, especially our own, seems to enrage us. But honestly, am I the only person in Toronto who thinks that Alexander Neef was one of the best things that ever happened to us?

I’m beginning to think I am, based on the many critical commentaries I’ve read about Neef over the years, and the damned-with-faint-praise evaluation of his tenure in the announcement by the COC of his successor, Perryn Leech. Maybe I’m overreacting, but if all I hear in regards to the COC’s future is talk about accessibility, community involvement, partnerships and fundraising, someone’s ideas about opera are different from mine – and, I’m guessing, from Alexander Neef’s as well.

I’m beginning to think I am, based on the many critical commentaries I’ve read about Neef over the years, and the damned-with-faint-praise evaluation of his tenure in the announcement by the COC of his successor, Perryn Leech. Maybe I’m overreacting, but if all I hear in regards to the COC’s future is talk about accessibility, community involvement, partnerships and fundraising, someone’s ideas about opera are different from mine – and, I’m guessing, from Alexander Neef’s as well.

Neef reinforced for me the idea that the goal of the arts should be excellence, not accessibility; relevance, not outreach. Excellence and relevance earn you accessibility and outreach, make those goals something easy and natural. Excellence ensures the arts shine, stand out with clarity; relevance cements the arts to their community. Both together ensure healthy audiences, financial stability, artistic worth. It is a trap laid by the non-artistic to make us think that the arts should be judged by the same criteria as other public spectacles – that art is, in the end, just another form of entertainment in a modern, pluralistic society.

It is a trap because the arts do not truly belong in that world. Once lured into the marketplace of entertainment, the serious arts will always be seen as elitist interlopers, and hated more, not less. That’s because the serious arts have different goals than the Blue Jays or Drake. Or should have. The arts sell value, to put it crudely – they traffic in meaning, in worth. Not in tonnage, audience involvement, clicks per thousand, bums in seats. Of course, art is useless if no one experiences it – but audience involvement is a means to an end in the arts, not the be-all and end-all of it.

That’s what I think Neef was striving for here in Toronto – excellence and relevance. If we were willing to listen, he taught us how the two could be made compatible and complementary. And he taught us something else as well – he showed us what it is like to play near the top of the heap in international artistic enterprise. It wasn’t always pretty – Neef was single-minded in his quest for international excellence; he could be autocratic; he wasn’t the schmooziest person you ever met; I’m told he could play favourites among his staff members. But that’s how it’s done if you want the world’s finest singers, directors, set designers and conductors to adjust their schedules and make Toronto, Canada one of their new international stopping points. That’s what it takes to be at or near the top of a tough, competitive, international artistic world.

It also explains why Neef leaned heavily on new and controversial productions during his time here, a constant source of friction during his tenure. He unashamedly challenged audiences to the breaking point, demanded the best of his artists and directors and musicians, pushed his audiences into constantly new territory. There was a single-mindedness about Neef that didn’t always translate well to amicable relations with the rest of the Canadian opera and musical community.

An example: although he was forced to backtrack eventually and commission a couple of Canadian operas, Neef repeatedly said during his tenure that he was opposed to nationalism in the arts as a matter of principle (and as a German man in his late 40s, let’s assume he understands a few things about nationalism we don’t). He hired Canadian singers for the COC, he once told me, because he hired them when he was casting director at the Paris Opera; he hired them because they were the best, not because they were Canadian. When he was therefore reluctant to commission a Canadian opera, composers in this country read the subtext, and were offended (and then when he commissioned Rufus Wainwright finally to write Hadrian, they were apoplectic).

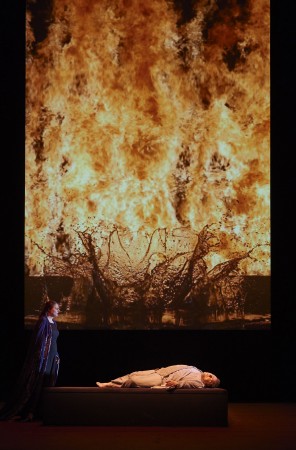

But Neef gifted us so many illuminating and crystalline evenings in the opera house, to me, it was all worth it. I think especially of the two Peter Sellars productions Neef presented here, a Tristan and Isolde with astonishing videos by Bill Viola, (and the return of Ben Heppner to a COC stage after an inexplicable 17-year absence) and Sellars’ Hercules, a Handel opera transposed to the American experience in Iraq. We saw work by Robert Carsen, the Alden brothers, David and Christopher, and the remarkable Don Giovanni of Dmitri Tcherniakov.

But Neef gifted us so many illuminating and crystalline evenings in the opera house, to me, it was all worth it. I think especially of the two Peter Sellars productions Neef presented here, a Tristan and Isolde with astonishing videos by Bill Viola, (and the return of Ben Heppner to a COC stage after an inexplicable 17-year absence) and Sellars’ Hercules, a Handel opera transposed to the American experience in Iraq. We saw work by Robert Carsen, the Alden brothers, David and Christopher, and the remarkable Don Giovanni of Dmitri Tcherniakov.

And the voices! Neef let us hear Sondra Radvanovsky as Queen Elizabeth and Norma, Christine Goerke as Brunhilde (before the Met heard her), Isabel Leonard as Sesto, Gerald Finley as Falstaff, Ferruccio Furlanetto as Don Quichotte and many others. We got to see and hear opera on the highest international level of performance for a decade. Was all of it brilliant? No. Was all of it successful? No, Did all of it fill houses? Quite the contrary. Was all of it worth it? For this operagoer, yes – a thousand times yes.

On the other hand, “the purpose of the theatre is to be full,” Neef himself once told me, quoting Giuseppe Verdi; with declining audience figures, and slightly anemic philanthropic numbers at the end of Neef’s tenure, perhaps it was understandable that the board of the COC decided a slightly different approach was necessary in the next phase of the institution’s life. They, after all, unlike me, have to balance budgets, worry about fundraising, fret over community partnerships, manage a company. I just got to go to the Four Seasons Centre for a decade and more, more often than not to come away dazzled, uplifted, changed – seized by art, the way art is supposed to seize you, but which it does so rarely in the world. That we could be so grabbed by the collar and shaken loose, and then, when it was done, still hop on the subway at Osgoode or the King car, was an especial treat, a homegrown treasure.

This is why I, for one, am thankful every day that Alexander Neef stopped here for a time – a good round dozen years, by the way, so hardly an opportunistic sojourn – and I hope he stands up to the rigours of a hyper-everything French cultural hothouse. Somehow I think he will.

I hope, as well, that the path he led us on remains clear and potent for the COC, and doesn’t get overgrown with the innumerable compromising weeds that are the bane of true art the world over.

Robert Harris is a writer and broadcaster on music in all its forms. He is the former classical music critic of The Globe and Mail and the author of The Stratford Lectures and Song of a Nation: The Untold Story of O Canada.