“I am Omicron-sidelined, but mending. But if I had known they were going to run this pandemic using the Greek alphabet, I’d have signed up for Nu? instead.”

“I am Omicron-sidelined, but mending. But if I had known they were going to run this pandemic using the Greek alphabet, I’d have signed up for Nu? instead.”

A friend of mine who has just come down with COVID emailed me that joke. A Jewish friend I should add, to explain the joke to those of you who have no reason to know that Nu is not only a letter of the Greek alphabet still available to name variants after, but also, in Yiddish, a word that translates roughly to “So?” in English, and like “So?” can carry all kinds of connotations depending on whether it is accompanied by a fatalistic shrug or a “so what” eye-roll.

In this case, the “nu?” would be a statement of communal resignation, the very best kind. “Nu – I have COVID? Who doesn’t?” In other words, we’re all in this together.

I admire my friend’s tenacity and good humour, because the rest of us aren’t making jokes about COVID – we’re just plain fed up with all of this – tired of talking about, thinking about, reading about, and living through it. Aren’t we?

The answer is yes, we are. So why, sir, are you writing another column about it? Why don’t you just leave bad enough alone?

The answer is yes, we are. So why, sir, are you writing another column about it? Why don’t you just leave bad enough alone?

Just this once more, I promise, because I’m beginning to think something significant has happened in virus-land over the past few weeks and months, where classical music is concerned, and it’s worth noting – and deliberating upon. So, please and thank you.

Hitting pause

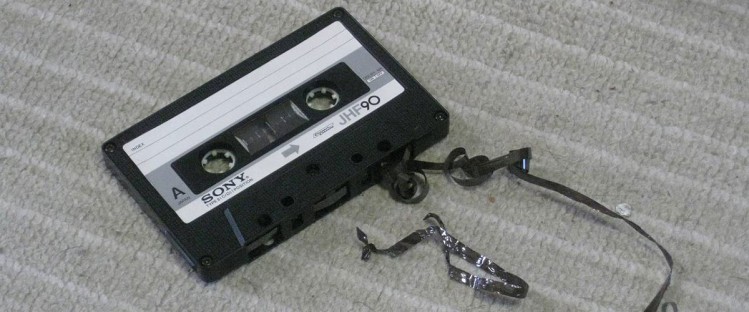

I might be imagining this, because it’s been a very long time since I had a cassette player, but I seem to recall that if you were listening to a cassette tape and put it on pause, and then forgot about it and just left it that way, eventually the machine, if it was a good machine, would turn itself off, to avoid straining that pause mechanism and breaking it. If it wasn’t a good one, it made for an ugly picture.

That metaphor I think perfectly captures where we are as far as the classical scene finds itself in North America these days. It’s different in Europe – they’ve been trucking along, masked and distanced, for some time in European halls. But here, with a few exceptions, very few, actually, we’ve basically been without concert music for two full years, and it’s not over yet. So I feel as though my finely engineered internal aesthetic mechanism has kicked in, acting just like that cassette override. What was once merely a pause is now a full stop. Something that was originally merely interrupted, ready to pick up again right where it left off, at a second’s notice, has now ground to a halt and will need to be begun all over again.

To my way of thinking, that’s a game-changing difference.

To my way of thinking, that’s a game-changing difference.

In the first place, for many musicians, the interruption in their performing cycles, in the rhythm and pace of their usual music-making, normally buoyed periodically and repeatedly by exposure to the living presence of an audience, has left their aesthetic sense congealed into a tight web of absence. It is one thing to be held mute and artistically celibate for a short, anxious period of time, with your instincts still ready and warm. It is something quite different to feel yourself forgetting the emotional rush of connection to an audience, a connection that is quite different from your tie to your instrument or to the music you’re playing.

Those latter two connections might still be intact – you still practice, you still play, you still create music – but the final rush of completion (which can only happen when other bodies are brought into range of the music and it vibrates within them as well as within yourself) is missing. I worry that musicians, after a while (to protect themselves from terminal loneliness) will find the sense of connection has gone from pause to stop. Does hitting “play” again automatically restart things? Or do they have to be learned all over again?

For audiences too, I wonder if something of the same is not also beginning to happen. We have been tantalized so often with the imminent end of this gigantic emptiness, only to find it extended again and again; I wouldn’t be surprised if we have given up hope for now. (I think of poor Gustavo Gimeno and the Toronto Symphony, waiting in suspense for over a year to perform, finally appearing in concert together to begin a new era, only to have that beginning snapped shut after three programs comprising seven concerts from November 10 to 20.

To be sure, my concerns might be the worst kind of overthinking. The memory and love of concert-going is so ingrained and intense for many of us that it will take nothing at all for us to regain our previous love affair with classical performance. Once this is done, it will be as though it never happened. Perhaps.

But something within me says that will not be the case, and that’s not an altogether bad thing. Classical music is not a completely obvious part of our lives, even for those of us who depend on it for aesthetic and emotional sustenance. It is fuelled by habit and convention, as much as anything. How we are going to react when we hit “play” on conventions and habits that have been shut down entirely, broken off, or stretched out of shape as thoroughly as they have been during the past 23 months.

Do I still want the same regimen of programming? I don’t know. But it’s entirely possible that I am ready for, and will not only want but expect, something new.

TSO and COC

There are more than a few indications that classical music has used the pandemic to rethink some of its basic programming assumptions, around inclusivity and diversity, repertoire, concert form and everything else. I know that, if nothing else, the musical institutions to which many of us will return are going to be quite different. To cite a couple of examples, here in Toronto (not completely because of the pandemic), both the Toronto Symphony and the Canadian Opera Company find themselves both under new management teams and facing quite different challenges than they could have anticipated in March of 2020.

The TSO has just hired Mark Williams, most recently with The Cleveland Orchestra, as their new CEO. As we’ve noted before, sheer bad pandemic luck has so far left Maestro Gimeno champing at the bit while being held back by circumstance from establishing his vision and sound and presence with the Orchestra. Through no one’s fault, it has been a long time since the TSO could count on continuity of artistic leadership. With Gimeno and Williams having collaborated effectively together in Cleveland, over a number of years, maybe the orchestra’s leadership luck has turned for the better.

I should also note that, for whatever reason, there has also been quite a sizable turnover among the players at the TSO, especially among first-desk positions; so there too the chemistry is changing. It’s hard to imagine the orchestra simply picking up where it left off when it finally starts performing again. And even harder to imagine that they would want to, even if they could. The world of symphonic classical performance in March of 2022 is just not the same as it was in March of 2020.

To say that the Canadian Opera Company seems like a completely different place under general director Perryn Leech than it was under Alexander Neef feels like an understatement. Not all of this change can be laid at the feet of the pandemic; in fact, two years of COVID-induced performance paralysis at the COC, for all its trauma, may have been something of a blessing in disguise for the institution. It seems clear that the COC Board had decided on a different sort of artistic vision for the company in the wake of Alexander Neef’s departure (which was accelerated, but not caused by the pandemic). It is a vision based on community and outreach, audience building and accessibility, including digital accessibility. The COC’s opening trio of productions under Leech – Madame Butterfly, La Traviata and The Magic Flute (interrupted sadly, by Omicron) – are quite a change from the more challenging repertoire we got used to under Neef. Having a buffer of a couple of seasons to separate the two visions may turn out to be to the COC’s great advantage.

Pangs

Paradoxically, it’s well-managed companies like Tafelmusik and Opera Atelier (to name but two of dozens),who maintained stable leadership during the pandemic, who are feeling the sharpest pangs of hunger from the long live-performing drought that has afflicted them. Well-functioning artistic companies need the adrenaline rush of production, before live human beings, repeatedly and constantly. It is their drug; it keeps them at the peak of their aesthetic capability. The lively arts have been in withdrawal for too long.

And we, the public on the other side of the footlights, have similarly withdrawn. We are about to return: weaker, perhaps; hungrier, perhaps; with changed sensibilities? For sure we should assume that we will not just get to hit “start”. The old machine of my musical self, like my old cassette deck, spent a long time in pause. Then it either felt like it finally had enough and prudently shut down. Or it didn’t, and has either burnt itself out or stretched the tape badly enough to distort our previous pleasure at what was on it.

And we, the public on the other side of the footlights, have similarly withdrawn. We are about to return: weaker, perhaps; hungrier, perhaps; with changed sensibilities? For sure we should assume that we will not just get to hit “start”. The old machine of my musical self, like my old cassette deck, spent a long time in pause. Then it either felt like it finally had enough and prudently shut down. Or it didn’t, and has either burnt itself out or stretched the tape badly enough to distort our previous pleasure at what was on it.

But it will be a new beginning, I suspect. Game-changingly different? It needs to be. Because every new beginning has the potential for tragedy, comedy and everything in between.

Robert Harris is a writer and broadcaster on music in all its forms. He is the former classical music critic of The Globe and Mail and the author of the Stratford Lectures and Song of a Nation: The Untold Story of O Canada.Story of O Canada.