It was surprising to me, in all the genuine affection that blossomed in America for the person of Alex Trebek, following his death in early November, that no one seems to have put their finger on what I think is the essential part of his appeal. I wouldn’t expect our American cousins to understand this, but I would have thought we up here might have clued in to it.

It was surprising to me, in all the genuine affection that blossomed in America for the person of Alex Trebek, following his death in early November, that no one seems to have put their finger on what I think is the essential part of his appeal. I wouldn’t expect our American cousins to understand this, but I would have thought we up here might have clued in to it.

Because in an America riven by mistrust, suspicion, the worst kind of passion, hatefulness even, Trebek radiated a calm, reassuring, intelligent, steady presence. He was the anti-Trump; he was a model of engaged civility; he was the quintessential Canadian. The true secret of his success.

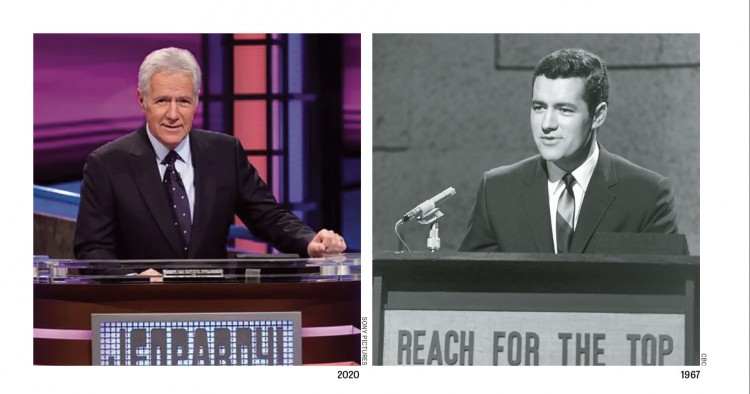

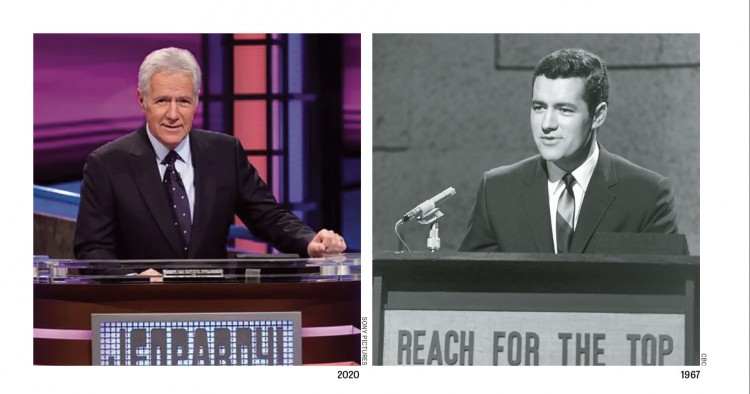

Those of us Canadians of a certain age knew of Trebek long before he took over from Art Fleming to be the host of a revived Jeopardy! in 1984. We had seen him for years on the CBC, hosting the truly great TV quiz show of all time – Reach for the Top – jousting and jesting with kids from high schools all over Canada. (How innocent we were in those days.) According to his Wikipedia entry, Trebek was producer Ralph Mellanby’s first choice to host Hockey Night in Canada in the early 70s. His mustache did him in it seems; the job went to Dave Hodge.

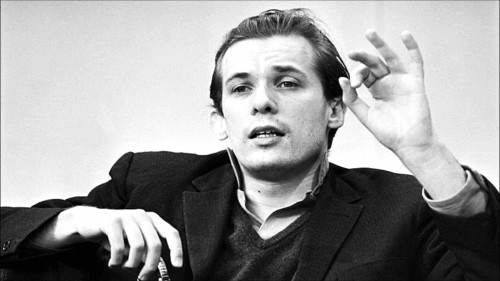

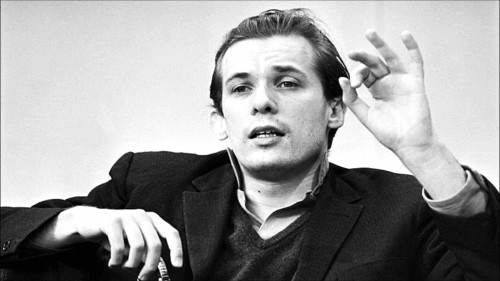

But most of us probably don’t remember, or even know, that Trebek and Glenn Gould appeared together in several of the many, many programs that Gould created for CBC Television in the 60s and 70s. OK, to call Trebek a collaborator with Gould may be stretching it a bit – Trebek, along with Bill Hawes and Ken Haslam, and several others, was a staff announcer at the CBC assigned at one time or another to work on the Gould specials. But they did appear together: Trebek introducing Gould playing Beethoven; Trebek quizzing Gould on his distaste for audiences; Trebek inviting us to join Gould next week.

The idea of a staff announcer was a BBC invention, later taken up by Canadian broadcasters. It was based on a supremely democratic notion: that all content was equally accessible to a modern, contemporary audience, or should be, so that the same person who read the news could introduce a program about pop music, or gardening, or a documentary about the mating habits of moose, or Gould talking about Beethoven’s “Tempest” sonata. It was all content for a curious audience, it was all content worth transmitting on prime time television on a weekday evening; it was the definition of modern Canadian civility. It was the atmosphere in which a young Trebek, born into a multicultural family (Ukrainian dad, Franco-Ontarian mom), in Sudbury, with his degree in philosophy from the University of Ottawa, learned about the world, the atmosphere in which the values so admired and honoured by his American audiences were honed.

The idea of a staff announcer was a BBC invention, later taken up by Canadian broadcasters. It was based on a supremely democratic notion: that all content was equally accessible to a modern, contemporary audience, or should be, so that the same person who read the news could introduce a program about pop music, or gardening, or a documentary about the mating habits of moose, or Gould talking about Beethoven’s “Tempest” sonata. It was all content for a curious audience, it was all content worth transmitting on prime time television on a weekday evening; it was the definition of modern Canadian civility. It was the atmosphere in which a young Trebek, born into a multicultural family (Ukrainian dad, Franco-Ontarian mom), in Sudbury, with his degree in philosophy from the University of Ottawa, learned about the world, the atmosphere in which the values so admired and honoured by his American audiences were honed.

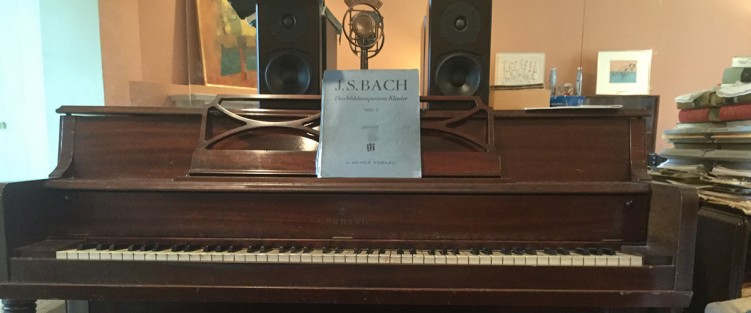

And those Gould programs, which actually ran in one way or another for over 20 years on the CBC, from the mid-50s to the late 70s (released on DVD by SONY Classical in 2011, still shamefully not available on the CBC website) were, and are still, astonishing: Gould playing and talking about Bach, reviewing the legacy of Richard Strauss, playing with Menuhin, performing Scriabin, in character as Theodore Slutz or Karlheinz Klopwiesser, taking part in one of those awkward, scripted interviews made to seem spontaneous that are so painful to listen to today. (Every one of Gould’s recorded interviews, including the famous conversations much later with filmmaker Bruno Monsaingeon, were scripted by Gould down to the last um and ah.) These broadcasts were unfailingly interesting, unfailingly egomaniacal, unfailingly erudite, and if you were someone like Trebek, CBC staff announcer in 1966, and assigned to one of these shows, you were expected to be able to, if not hold your own with Gould, at least not embarrass yourself.

The network was based on the notion of a certain universality of interest, a certain belief in the ability of us all to understand and appreciate the world on many levels simultaneously – precisely the values that Jeopardy!, of all things, presented to America night after night in its own, modest way – the reason that Trebek was such a perfect fit to be its host. Invented by Merv Griffin (developed from an idea his wife came up with on an airplane as the couple returned to NYC from a visit to her hometown of Ironwood, Michigan) Jeopardy! is based on the notion that intelligence matters, that information is valuable for its own sake, not as a weapon to create political realities, and its continuing popularity in the riven America of 2020 is proof that those values have not entirely departed from the world. And Trebek, in his very modest, but sure and unassailable Canadian way, stood for those values. Which is why a game show host, of all things, could legitimately emerge as a powerful cultural icon in the 21st century. We tend to forget here (or our preternatural modesty has blinded us to the fact) that we stand for something real in the world, we Canadians – something that linked a musical genius and a professional announcer, that made Gould and Trebek not as unlikely a pair of cultural models as you might think.

Part of it was an openness to the world, a lack of cultural and intellectual boisterousness that manifested itself in Gould as a thrilling desire to interrogate cultural and musical truths long held to be inviolable, and in Trebek as a simple, but steady, belief in honesty, curiosity and decency. Part of it was an understanding, born of cohabiting a continent with the loudest nation on earth, of the value of silence, modesty, and contemplation. Part of it was an understanding that a country so blessed with natural wonders, but cursed with them as well, demanded a certain self-reliance, an understanding that, in the end, it is you yourself who must decide your worth, that you are accountable, finally, to your own set of values. That’s what kept Gould in Canada – the knowledge that the US would have overwhelmed his relatively fragile, but essential sense of self – and that’s what allowed Trebek, even though he became an American citizen, to remain very palely Canadian despite years of being scorched by the hot American sun of Los Angeles celebrity.

The CBC, of course, has long abandoned the philosophy of cultural democracy that could link two minds so wildly different as those of the once-in-a-lifetime Gould and the more amenable (which is not to say characterless) Trebek. And, to be fair, the world they temporarily co-inhabited is 50 years distant. But the ability of culture, in all its forms, high and low, Bach fugue and Final Jeopardy query, to provide a source of illumination that shines on us all, despite all our differences, has not entirely disappeared from the world. Glenn Gould blazed that illumination blindingly; Alex Trebek, much more modestly. But both were sources of light in the world. A very Canadian light.

Robert Harris is a writer and broadcaster on music in all its forms. He is the former classical music critic of the Globe and Mail and the author of the Stratford Lectures and Song of a Nation: The Untold Story of O Canada.

Here’s a reminder for those of you who think we Canadians have no substantial international intellectual clout. You are wrong. So wrong. And how do I know? Because Le Monde, France’s leading newspaper, told me.

Here’s a reminder for those of you who think we Canadians have no substantial international intellectual clout. You are wrong. So wrong. And how do I know? Because Le Monde, France’s leading newspaper, told me.