As we enter into this extraordinary exercise in willed sensory deprivation that is our new reality (and how bizarre it is), I have found myself surprised by almost all of my reactions to the coronavirus. Not the least of which are my reactions to music. If I wanted to be rational about it, I would have to admit that while yes, I enjoy going to concerts, a good 90 per cent of the music I actually listen to – on the radio, online, from CDs, and files and even, heaven help me, on records – is still available to me. My listening habits really shouldn’t haven’t changed that much at all.

As we enter into this extraordinary exercise in willed sensory deprivation that is our new reality (and how bizarre it is), I have found myself surprised by almost all of my reactions to the coronavirus. Not the least of which are my reactions to music. If I wanted to be rational about it, I would have to admit that while yes, I enjoy going to concerts, a good 90 per cent of the music I actually listen to – on the radio, online, from CDs, and files and even, heaven help me, on records – is still available to me. My listening habits really shouldn’t haven’t changed that much at all.

And yet, they have. The musical impact on me of the coronavirus has been profound. Unexpectedly so.

For one thing, I can hardly bear to listen to music at all these days. Not a note. I assume I’m in a tiny minority because COVID-19 playlists are popping up everywhere. I’ve tried listening to a few – I never get very far. I’m just not moved. Even some of my favourite composers are unbearable to me these days. Beethoven I find appalling. All that power and desperate projection of will strike me as completely wrong-headed these suffering days. Bach’s crystalline mathematical perfection likewise comes across, to me, as an utterly tone-deaf response to a world seemingly without ballast or divine balance. Who is left? Mozart, of course, to my mind the perfect coronavirus composer in his deeply ambiguous, but fundamentally loving relationship to the world. I just listened to the last act of Figaro the other day, which begins with that amazing G-minor Cavatina of Barbarina (my nominee for Mozart’s most underrated aria, right up there for the expression of pure grief with Pamina’s Ach, ich fühl’s, although Barbarina is lamenting the loss of a pin, not a lover) and ends with that extraordinary heaven-sent hymn to forgiveness (more religious than anything in the Requiem) that perfectly sums up Mozart’s fundamentally confused relationship to the world. That confusion, the combination of comedy and depth, farce and love, the unexpected breaking out of the purest feeling in the middle of nonsense is such a perfect reflection of our present state, except ours is one of horror, not farce, that I found myself, much to my surprise, awash in tears at opera’s end, weeping not just for the Countess – surely the most perfect, angelic creature in opera – but for us all.

So if I haven’t been listening to much music during this numbing, get-through-each-day-one-at-a-time pandemic, what have I been doing? Well, I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about music itself and what it means for us, and again, have surprised myself. I mentioned earlier that I admit to being a child of the recording – most of the most significant musical experiences I’ve had in classical music, and almost all of them in pop music, have been through records. Consequently, all my life I’ve been somewhat skeptical of the Frankfurt school of thought, of Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin, that consistently undervalued, and even opposed the recording as a form of musical enlightenment. Adorno felt that the recording robbed music of its essential communal nature; Benjamin felt that mechanical reproductions of art lacked a certain “aura” that the originals enjoyed. I disagreed. The recording, I felt, had an aura of its own, different from that of a live performance, but very real nonetheless; and the private listening to music that the recording afforded certainly made for an experience quite separate from that of a concert hall, but no less worthy.

So if I haven’t been listening to much music during this numbing, get-through-each-day-one-at-a-time pandemic, what have I been doing? Well, I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about music itself and what it means for us, and again, have surprised myself. I mentioned earlier that I admit to being a child of the recording – most of the most significant musical experiences I’ve had in classical music, and almost all of them in pop music, have been through records. Consequently, all my life I’ve been somewhat skeptical of the Frankfurt school of thought, of Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin, that consistently undervalued, and even opposed the recording as a form of musical enlightenment. Adorno felt that the recording robbed music of its essential communal nature; Benjamin felt that mechanical reproductions of art lacked a certain “aura” that the originals enjoyed. I disagreed. The recording, I felt, had an aura of its own, different from that of a live performance, but very real nonetheless; and the private listening to music that the recording afforded certainly made for an experience quite separate from that of a concert hall, but no less worthy.

The coronavirus has proven to me that I was wrong on both counts.

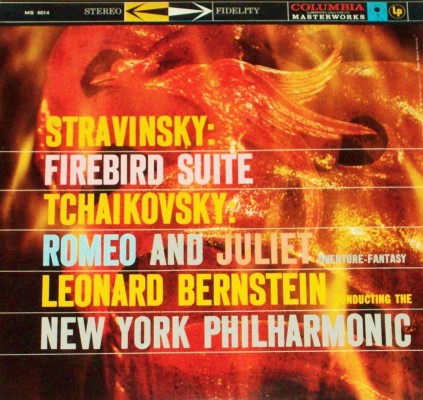

Don’t ask me to explain, because I’m not sure I understand myself, but the fact that I can’t go to a concert anymore has also robbed my recordings of the aura they once had. It doesn’t make sense: one shouldn’t have anything to do with the other. Whether or not the TSO is performing Stravinsky in Roy Thomson Hall tomorrow shouldn’t influence how much I love my 60-year-old recording of Bernstein conducting The Firebird. But it does. I can feel it. I can only surmise that when I was listening to my recordings, I was unconsciously imagining myself at a live concert; and that fantasy was actually a central part of my listening experience. Without the potential of a live performance in my imagination, the record made little sense. I enjoyed the recordings because I knew I could experience a live concert when I wanted, even if I went to very few. Now that I no longer can, even if only temporarily, the power of the recording has eroded for me. Without live concerts, records mean considerably less, I’ve discovered. Much to my surprise.

Don’t ask me to explain, because I’m not sure I understand myself, but the fact that I can’t go to a concert anymore has also robbed my recordings of the aura they once had. It doesn’t make sense: one shouldn’t have anything to do with the other. Whether or not the TSO is performing Stravinsky in Roy Thomson Hall tomorrow shouldn’t influence how much I love my 60-year-old recording of Bernstein conducting The Firebird. But it does. I can feel it. I can only surmise that when I was listening to my recordings, I was unconsciously imagining myself at a live concert; and that fantasy was actually a central part of my listening experience. Without the potential of a live performance in my imagination, the record made little sense. I enjoyed the recordings because I knew I could experience a live concert when I wanted, even if I went to very few. Now that I no longer can, even if only temporarily, the power of the recording has eroded for me. Without live concerts, records mean considerably less, I’ve discovered. Much to my surprise.

Which explains, I think, my last reaction to the virus, which is to feel a great deal of pain on behalf of my musician friends and colleagues. It sounds, I know, a bit elitist and out of touch to mourn for musicians when so many of our other fellow citizens are hurting so profoundly and face real dislocations in their lives. Worrying about art seems to be a bit on the frivolous side when the basic underpinnings of our society seem to be eroding – witness the brouhaha over the 25 million-dollar grant to the Kennedy Centre included in the midst of a 4.5 trillion US stimulus package, which was so controversial it needed Donald Trump’s personal endorsement to be included. (it represents five one hundred thousandths of the total, in case you’re wondering.) But musicians, especially classical musicians, are unlike any other set of workers in this cryogenic suspension of ours, even other performing artists, like actors or dancers. Classical musicians expect to be in front of an audience regularly – even pop musicians only tour from time to time. Performing live is like breathing to classical musicians, a natural outlet that makes all their other activities – practising, studying, rehearsing – make sense. Take the performances away, and suddenly nothing makes sense. It’s as though my musician friends are all in the artistic ICU, hooked up to aesthetic ventilators. Their normal functioning has been disturbed – and not just theirs, but ours as well. It’s a strangely unsettling experience.

The virus has reminded us that music is the most social of the arts – it needs a functioning collective of performers, administrators, entrepreneurs and audience members to be most fully itself. It can’t really exist in a recorded vacuum. It needs real live bodies to exist – performing bodies, and listening bodies. When we connect physically through music, we create something together that didn’t exist separately before – this was the essence of Adorno’s complaint about the record and radio broadcast, the lack of that physical and psychical creativity of which music is capable. I’m becoming increasingly sure that the world that will emerge, blinking and confused, at the other end of this cataclysm is going to be very new in many ways – we won’t be returning to as much as we think, or hope. So we will need music, as we always have, to help us reconnect with each other, and make sense of what we are collectively experiencing when the time comes.

Let’s hope music retains the power to do so, so that when it returns to us, in its full communicative splendour, whenever that is, it will help us take stock of the new tomorrow that awaits us.

Robert Harris is a writer and broadcaster on music in all its forms. He is the former classical music critic of the Globe and Mail and the author of the Stratford Lectures and Song of a Nation: The Untold Story of O Canada.